Refugees unwelcome: Increasing surveillance and repression of asylum seekers in the “new Moria” refugee camp on Lesvos

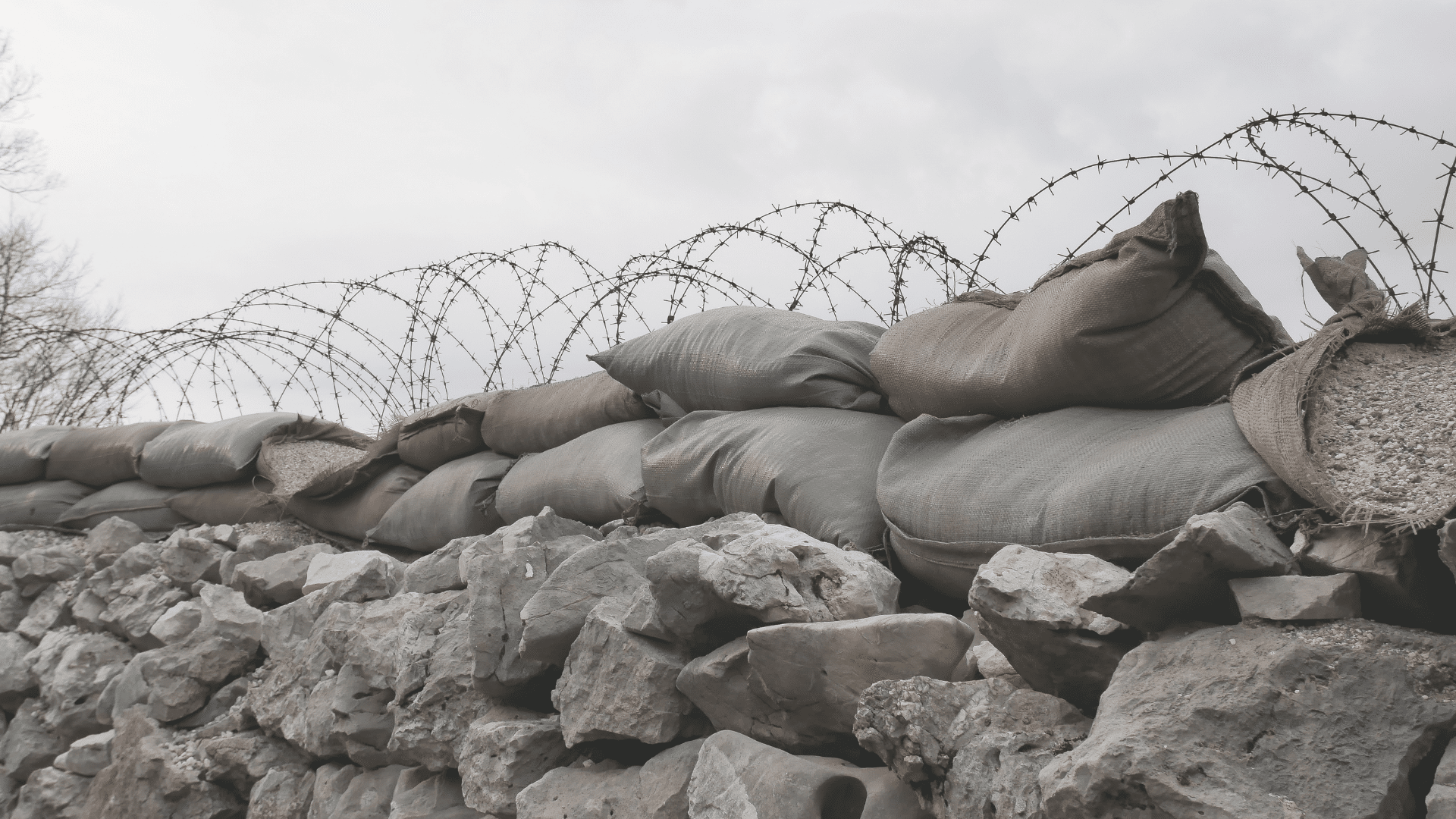

This blog discusses the conditions for asylum seekers on the Greek island Lesvos after the notorious Moria camp burned to the ground in September 2020.