Protecting children’s digital bodies through rights

Children are becoming the objects of a multitude of monitoring devices—what are the possible negative ramifications in low resource contexts and fragile settings?

Children are becoming the objects of a multitude of monitoring devices—what are the possible negative ramifications in low resource contexts and fragile settings?

Thousands of people have died in the Mediterranean Sea in the past few years in an attempt to reach Europe. What happened two days ago was only the most recent episode in this human-made, ongoing catastrophe.

The Norwegian-registered vessel Ocean Viking, operated by Médecins Sans Frontières, has recently been at the centre of a debate that has become dominated by one assumption: that search-and-rescue (SAR) operations are encouraging people to attempt to cross the Mediterranean.

Over the summer, the World Food Programme (WFP) — the world’s largest humanitarian organisation — got into a pitched standoff with Yemen’s Houthi government over, on the surface, data governance. That standoff stopped food aid to 850,000 people for more than two months during the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

More than a million migrants crossed the Mediterranean in an attempt to reach Europe during the 2015 refugee crisis, the vast majority arriving either in Greece or Italy. The following year the European Union entered the so-called “EU-Turkey Deal”, a statement of cooperation between European states and the Turkish government.

In the wake of the scandal in Haiti revolving around sexual misconduct by Oxfam staff in the aftermath of the 2010 Earthquake, the aid sector is now engaging in ‘safeguarding’ exercises. However, despite good intentions, the safeguarding response has some problematic qualities which need to be discussed.

Penal humanitarianism – the combination of punitive sentiments and humanitarian ideals – is increasingly moving the ‘power to punish’ beyond the state – not only in relation to migration and international criminal justice; but also in relation to the use of military force to protect vulnerable populations facing systematic violence.

Until fairly recently, criminal prosecution of conflict-related sexual violence was practically unheard of. Today, criminal prosecution has become key in dealing with conflict-related sexual violence.

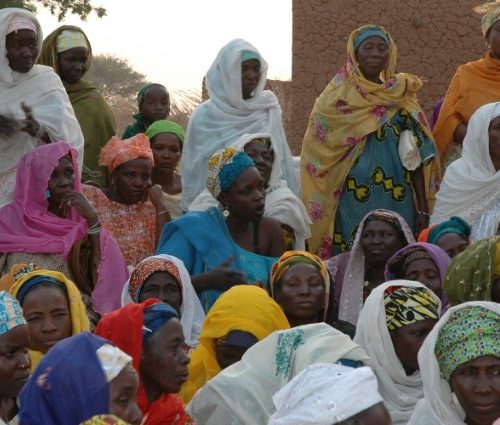

Drawing on the case of Niger, this blog examines some of the processes through which the EU projects penal power beyond Europe and its allegedly humanitarian rationale.

How do individuals tasked with carrying out state policies on border control react to direct encounters with human suffering, and what are the implications of such interpersonal encounters on border studies?

Examining UK ‘managing migration’ initiatives, illustrating a securitisation of humanitarian aid.

This Border Criminologies blog series takes a closer look at the intersections of humanitarian reason with penal governance, and particularly the transfer of penal power beyond the nation state.