Drawing on the case of Niger, this blog examines some of the processes through which the EU projects penal power beyond Europe and its allegedly humanitarian rationale.

23.05.2019

Eva Magdalena Stambøl (Aalborg University)

This is the fourth post in a six-part series on ‘Penal Humanitarianism’, edited by Kjersti Lohne. The posts centre around Mary Bosworth’s concept and Kjersti Lohne’s development of penal humanitarianism, and how penal power is justified and extended through the invocation of humanitarian reason. The blog posts were first posted on the “Border Criminologies” blog, and are re-posted here.

Projecting European penal power beyond Europe: Humanitarian war on migrant smuggling in West Africa

The European Union (EU) and its member states are increasingly pushing countries in the southern (extended) neighbourhood to criminalise unwanted mobility, and bolstering their internal security apparatuses and borders. The objective of this ‘internal security assistance’ is to combat transnational security threats and illicit flows of goods and people allegedly en route to Europe. Based on my doctoral research, which has included fieldwork in Niger, Mali, Senegal and Brussels, this post reflects on the EU’s increasing tendency of crime control ‘at a distance’ in West Africa.

Penal power is the power to render an activity criminal and to enforce criminal law, which is neatly entwined with a state’s sovereignty. For instance, Vanessa Barker writes how the reinforcement of national borders within Europe can be seen as a recent expression of state-craft where penal power is particularly salient. Yet Mary Bosworth argues that humanitarianism allows penal power to travel beyond the nation state, as can be observed in cases such as England’s aid to the building of prisons in its former colonies to which it can transfer and expel prisoners from these countries. Developing Bosworth’s concept of ‘penal humanitarianism’ further, Kjersti Lohne shows, through the supranational case of the International Criminal Court (ICC), how the power to punish is particularly driven by humanitarian reason when punishment is disembedded from the nation state altogether.

This blogpost examines some of the processes through which the EU projects penal power beyond Europe and its allegedly humanitarian rationale. I draw on the country case of Niger, which is also an example often used by the EU to showcase a well-functioning partnership in stopping migration to Europe through criminalisation and ‘breaking the business model of human smugglers.’ In this case, penal power is not actually detached from the state. While the EU is both a supranational and inter-governmental entity, I argue it could also be seen as something like ‘pooled European penal power’. This European penal power works through a third state by bolstering this state’s own penal power, without being entirely able to control how this power is in turn utilised in practice. So what is the relation between sovereignty and penal power when the EU border is externalised to West Africa?

European penal power in West Africa

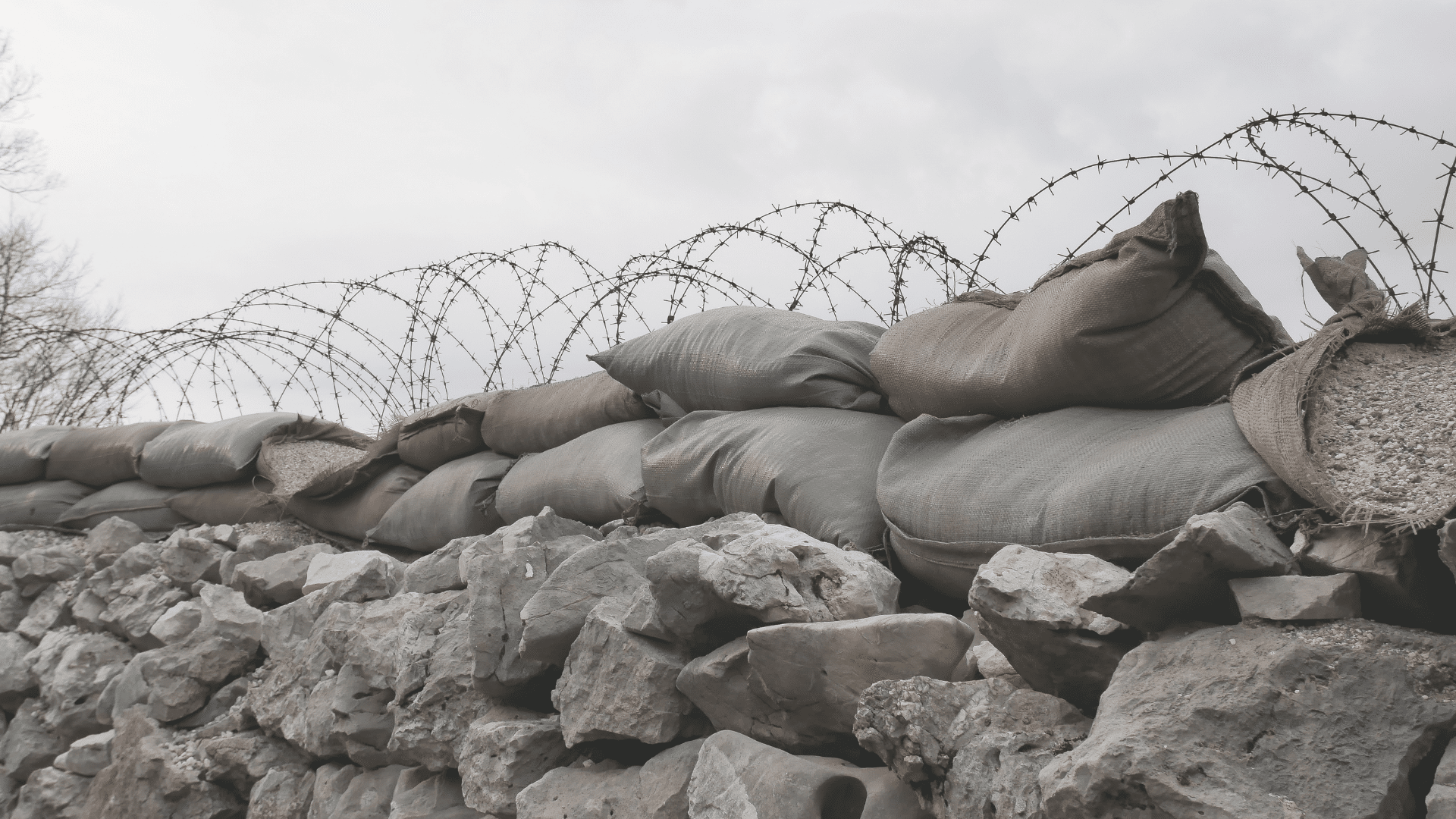

West Africa, and the Sahel region that cuts across the Sahara Desert, have become a priority to the EU and its member states in terms of controlling unwanted mobility. Conceptualising security threats as flows of illicit or dangerous commodities and people crossing borders and spilling into Europe, the EU is now seeking ‘partnerships’ with African regimes to build barriers further south. Substantial efforts are being put into shaping West African penal codes and reinforcing criminal justice and security apparatuses to deal with illicit flows. In order to incentivise an actual change, EU aid and budget support, on which many West African countries depend, is increasingly made conditional upon the adoption of security strategies, the reform of internal security forces and the securing of borders.

One such example is the EU’s much celebrated ‘partnership’ with President Issoufou of Niger. In 2015, conspicuously coinciding with the European ‘migration crisis’, Niger adopted a law criminalising ‘migrant smuggling’. The EU assisted Niger in drafting the law and provided advice, training and capacity-building for its enforcement. This was done, among other, through the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission EUCAP Sahel Niger, and through projects financed by the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. EU aid to Niger continued to grow, and in December 2017 the European Commission announced 1 billion euro in support by 2020, as Niger had demonstrated ‘strong political willingness and leadership’ to confront challenges. Indeed, in 2016 Nigerien authorities started rigorously enforcing the law, selectively in the northern town of Agadez which had figured in the international press as the hub for migrants travelling to Libya and Algeria. Since then more than 130 ‘migrant smugglers’ have been arrested and their vehicles seized, and the number of migrants crossing into Libya registered by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) is reported to have dropped. The Niger migrant smuggling law and its enforcement is seen as so successful that the EU wants to replicate it in other Sahel countries as well.

Penal humanitarianism at Europe’s extraterritorial border

The rationale behind the EU’s fight against ‘migrant smugglers’ in Niger is framed as a humanitarian obligation: stopping migrants from travelling through Niger equals saving them from dying in the hands of evil people smugglers or in Libyan detention camps. This is not very different from Libya further north, where the EU’s training of the ‘coast guard’ is justified by saving people from drowning in the Mediterranean. Nor is it very different from the EU’s external borders where, according to Katja Franko and Helene Gundhus, the discourse of protecting the human rights of migrants permeate the borderwork of Frontex officers.

Civil society organisations (CSOs) in Niger and the local population in Agadez are strongly opposed to the criminal category of ‘migrant smuggling’ as it relates to Nigerien reality. Guiding people through the desert has been a noble, traditional role for centuries, and now-called migrant smugglers are not ‘organised crime syndicates’ as the European Commission assumes (also see Sanchez, 2015). Moreover, CSOs claim the new law is de facto suspending the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Protocol on free movement for ECOWAS citizens, which most of the migrants are. Intra-African migration is a crucial livelihood strategy in a region fraught with periodical extreme drought and climate change. Research also documented severe de-stabilising effects of the law enforcement as the economy of the region of Agadez collapsed, leading the local population to lose their livelihoods, fueling economic frustrations and anger, and increasing armed banditry and general insecurity.

Conclusions

The case of EU policies in Niger corroborates the argument that penal power can take on a humanitarian rationale when it travels. This seems to be particularly the case when criminal justice, migration control, international development and foreign policy intersect. Complicating the relationship between sovereignty and penal power, Niger’s sovereignty is both hollowed out by mediating European ‘pooled’ penal power and at the same time boosted by the co-option of aid into President Issoufou’s personal goals. What is certain is that the security of Europe does not equal the human security of migrants or local Nigerien communities, nor does the latter equal the security of the Nigerien regime.