Penal humanitarianism – the combination of punitive sentiments and humanitarian ideals – is increasingly moving the ‘power to punish’ beyond the state – not only in relation to migration and international criminal justice; but also in relation to the use of military force to protect vulnerable populations facing systematic violence.

23.05.2019

Teresa Degenhardt (Queen’s University Belfast)

This is the sixth and final post in a series on ‘Penal Humanitarianism’, edited by Kjersti Lohne. The posts centre around Mary Bosworth’s concept and Kjersti Lohne’s development of penal humanitarianism, and how penal power is justified and extended through the invocation of humanitarian reason.

The blog posts were first posted on the “Border Criminologies” blog, and are re-posted here. This post argues that the 2011 Nato intervention in Libya mimics a reaction similar to that of the state, suggesting that the ‘right to punish’ is re-articulated outside the state and within the international.

Penal humanitarianism – the combination of punitive sentiments and humanitarian ideals – is increasingly moving the ‘power to punish’ beyond the state – not only in relation to migration and international criminal justice; but also in relation to the use of military force to protect vulnerable populations facing systematic violence.

Since the 1990s, the use of military interventions has been increasingly launched following humanitarian sentiments towards far away populations subjected to mass violence and in conjunction with human rights imperatives, conveying the idea of ‘doing justice’ through war. This inscription of war among the tools to sanction wrong-doing is linked to the increased status of human rights as global norms for the protection of individuals from violence.

In this post, I argue that the 2011 Nato intervention in Libya shows how human rights are treated with a mix of political condemnation, judicial proceedings, and military might, to indicate wrong-doing within the international- and thus mimic a criminal justice reaction similar to that of the state. This suggests that the ‘right to punish’ of the state – its ‘jus puniendi’- is now re-articulated outside the state and within the international.

Under international law, sovereign states are autonomous and in control of their territory and their population. In this line of thought, the international community has no power to interfere with what happens within the borders of a state. However, against the context described above, in the last 30 years the individual, not the state, has moved to the centre of the protection afforded by international law. Therefore, the international society has the duty to protect individuals when states fail; thus, legitimising military operations. These military practices operate outside state power and often feature multiple states and actors, in ways that change our understanding of what counts as punishment, intersecting with humanitarian sentiments, foreign policy, and postcolonial practices.

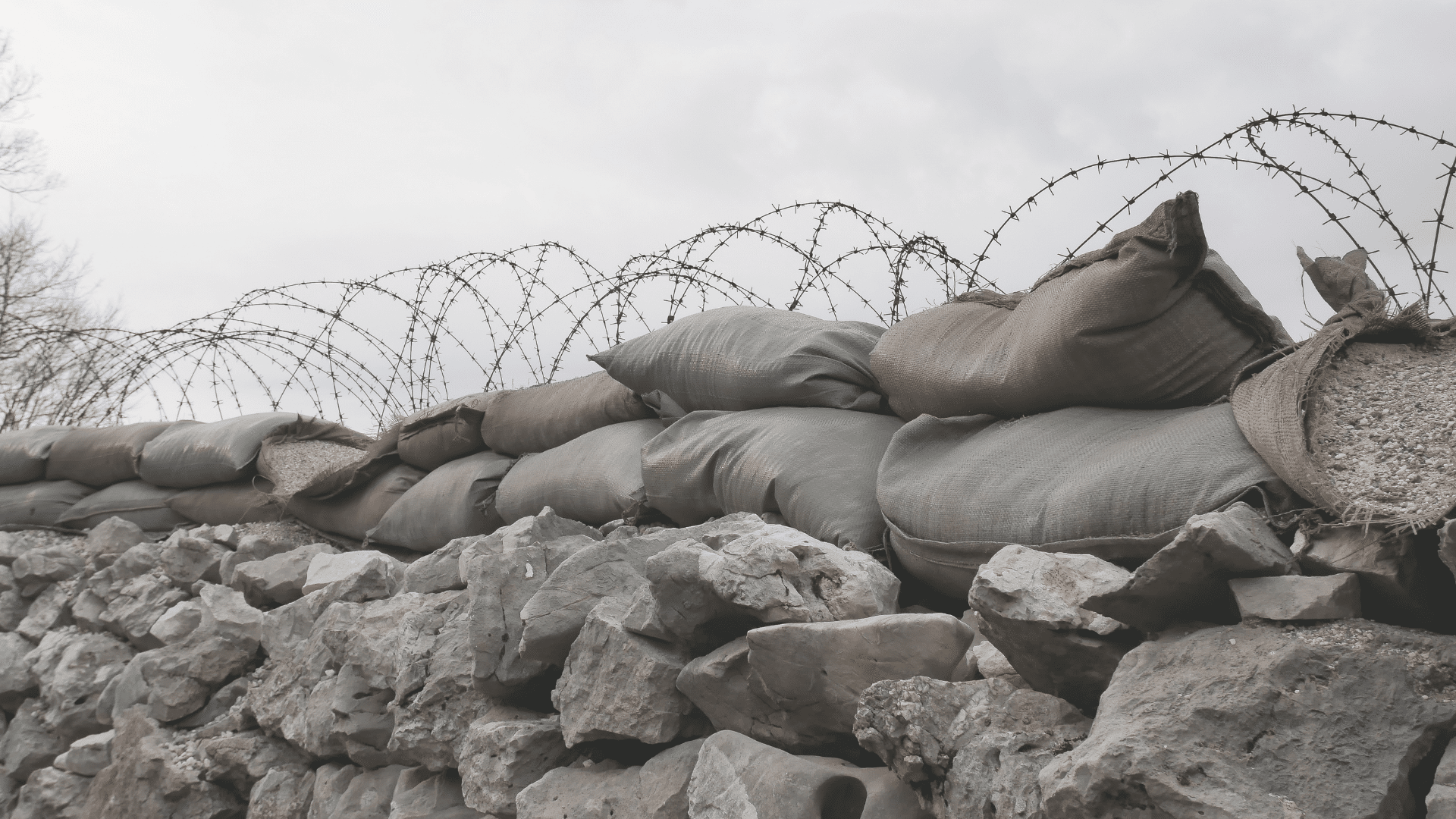

The 2011 military intervention in Libya was launched with the approval of the UN Security Council under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), a rule that sanctions the international community’s ‘collective responsibility to assist populations’ under threat of, or actually experiencing, mass violence in situations where the host state fails to protect them (art 138-139). The UN Resolution authorising military intervention under R2P came as a response to accusations by various power figures, including UK Prime Minister Cameron and French President Sarkozy, of gross human rights violations by the Gaddafi regime against civilians protesting his regime. In this way, powerful actors in the Global North passed a judgment on Libyan elites and their criminality. NATO, swiftly took the lead and intervened militarily, claiming its role as protector of the Libyan people, and framing itself as the authority in charge of enforcing human rights in the region. In other words, it established its jurisdiction over local events. The Libyan leaders – i.e. Gaddafi, his son, acting Prime Minister Salif Al Islam, and former intelligence chief Al Senussi – were indicted by the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor Moreno Ocampo, evidencing that military operations now function within a criminal justice framework.

Linking military might with legal prosecution (or at least court activation) shapes our understanding of war as an ethical mechanism that censures human rights violations perpetrated by individual criminals. As argued by Lohne, these manifestations of penal humanitarianism require more consideration on the effects that these practices have on our understanding of punishment and sovereignty and on the sort of tension these may engender.

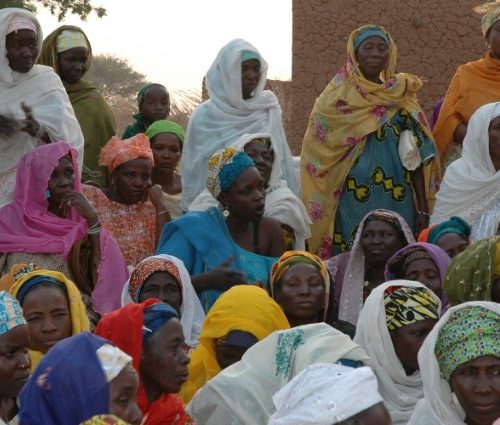

These punitive military operations launched to sanction and end mass violence are often followed by practices of peacekeeping aimed at getting local populations to accept specific rules of coexistence, establishing the local sovereign state and its criminal justice systems through human rights and international standards. After the NATO victory and the death of Gaddafi in controversial circumstances, the UN sent a small contingent to the country to assist with the establishment of peace. These representatives of international society operated on the ground as experts on democratic institutions, training the locals in human rights norms, encouraging them to adopt specific institutional structures, laws and international standards.

The UN Secretary General Reports show how these international experts watched and judged local authorities on their institutional practices. UN officials not only urged new authorities to adopt human rights standards as norms, but also constantly monitored their exercise of power making sure it is informed by international best practices. These international experts effectively attempt to operate some sort of pedagogy of liberal institutions, to shape the local sovereign state, at the same time as they tie its power to the Global North; thus, incorporating the new sovereign and its population in its remit. In doing so, the Global North expands its reach; it shapes governance through sovereign structures at the local level while re-articulating sovereign power at the global level. These two sovereign powers should not be seen as hierarchically constituted but as uncomfortably intersecting. The new norm of responsibility to protect re-articulates the principle of protection within the international society, in turn relocating the state’s power and right to punish, as envisioned within the well-known Hobbesian Leviathan idea. This is symptomatic of an international society increasingly thought of as united through reference to humanity, in which the individual is at the centre of protection. However, this framework problematically renders war and in general military force the best instrument to protect life and create order, at the same time as it legitimates neo-colonial enterprises. While not unprecedented, this way of conceptualising war is odd, given that war used to be thought of as the epitome of disorder (anomie), with military strategists confirming that ‘you know how a war may start but never how it ends’.