How do individuals tasked with carrying out state policies on border control react to direct encounters with human suffering, and what are the implications of such interpersonal encounters on border studies?

23.05.2019

Katja Franko (University of Oslo) & Helene O.I. Gundhus (University of Oslo)

This is the third post in a six-part series on ‘Penal Humanitarianism’, edited by Kjersti Lohne. The posts center around Mary Bosworth’s concept and Kjersti Lohne’s development of penal humanitarianism, and how penal power is justified and extended through the invocation of humanitarian reason. The blog posts were first posted on the “Border Criminologies” blog, and are re-posted here.

Moral discomfort at the border: Understanding penal humanitarianism in practice

A growing body of recent scholarship has pointed out the intricate connections between the exercise of penal power and humanitarianism in general, as well humanitarianism at the border (see e.g. Fassin; Bosworth; Lohne). This research has shown the centrality of humanitarian ideals and language within different penal sites and programs such as prison building programs abroad, the International Criminal Court and various border control practices. Humanitarian ideals are exposed as central to governmental discourses, disembedding penal power from the nation state, and often used to legitimise highly controversial border practices as matters of saving and protecting lives or promoting human rights.

Mary Bosworth, for example, observes that ‘human rights rhetoric and practices can justify the exercise of coercive state powers, even if their supporters wish it were otherwise’. In these contexts, humanitarianism is understood to function as a smokescreen and a technique for glossing over the ethically problematic and messy realities of border control. As Didier Fassin suggests: ‘Humanitarianism has this remarkable capacity: it fugaciously and illusorily bridges the contradictions of our world, and makes the intolerableness of its injustices somewhat bearable. Hence, its consensual force.’ In this post, we wish to contribute to the debate by drawing attention to the somewhat neglected aspects of humanitarianism in practice.

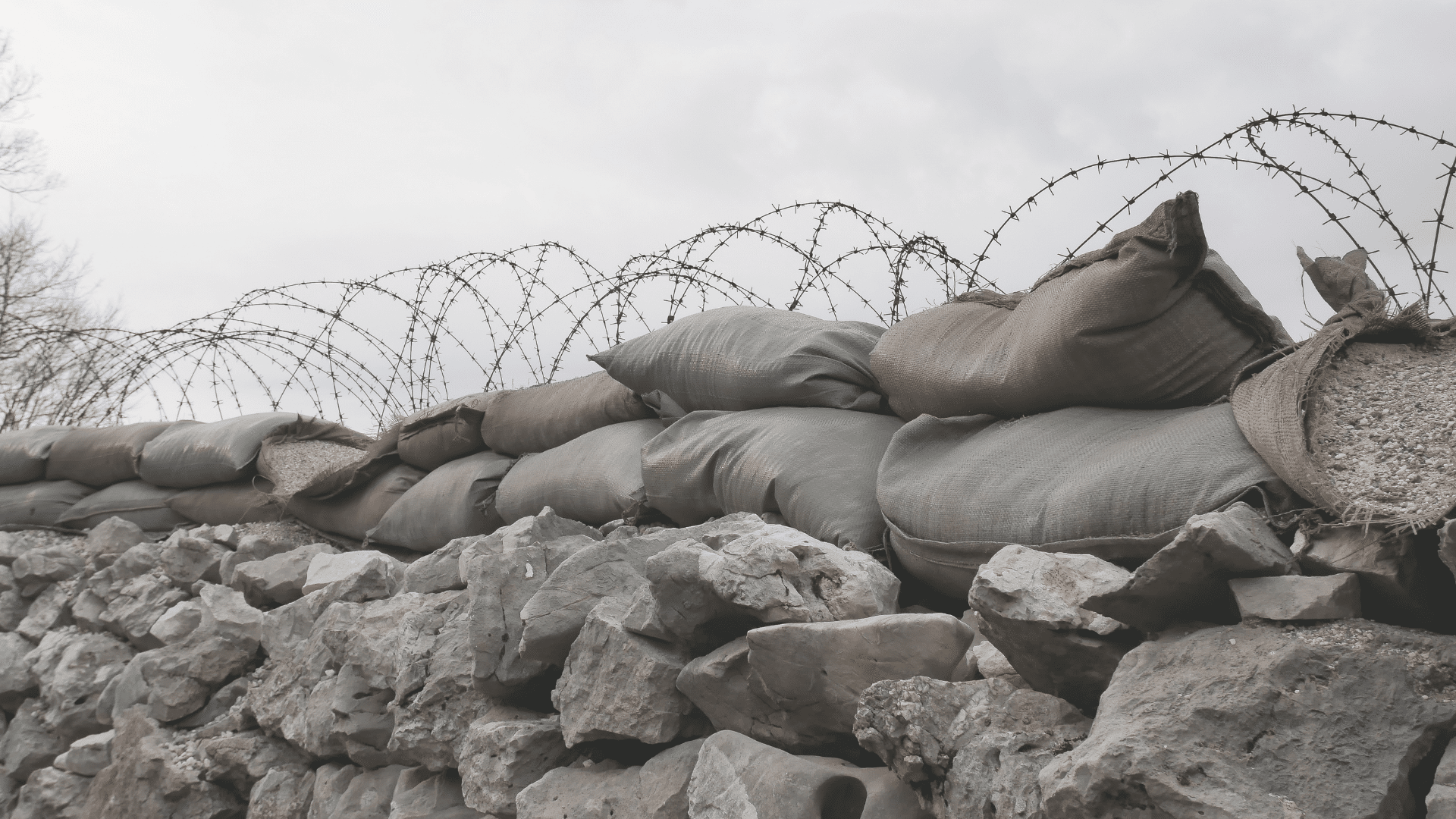

In our own work, we have analysed the deployment of humanitarian language and the discourse of human rights in Frontex operations. The precarious situation at Europe’s external borders is creating an irresolvable tension between the interests of European states to seal off their borders and the respect for fundamental human rights. The paradox of the centrality of ‘saving lives at sea’ in EU policy documents illuminates the disconnection between the performative aspects of humanitarianism and its operational use. The study revealed obvious contradictions and disjunctions between the objectives of state security and a lack of concern for migrants’ vulnerability, transferred into member states’ national risk assessments indicators.

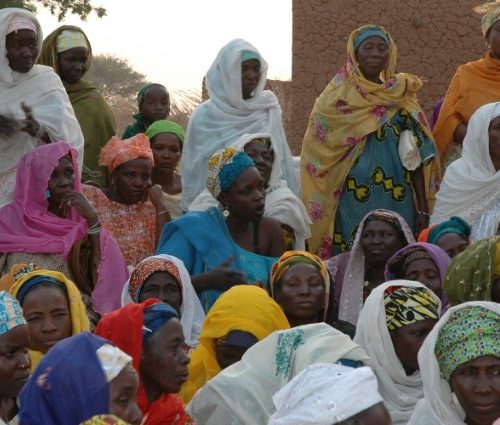

However, we also uncovered the centrality of humanitarian sentiments in the narratives of police officers tasked with performing everyday border control. Indeed, the interviews with Frontex officers revealed a rather complex picture. While the humanitarian discourse clearly does a certain kind of performative ‘work’, it also seems to be to some extent internalised and appropriated by actors on the ground. Many officers talked with deeply felt seriousness and compassion about providing clothing and medicine for cold, wet and sick migrants. Some experienced the situation to be so serious that they drew analogies to the WW2. As one experienced officer described the situation in Greek detention centres: ‘It was like watching, it is terrible to say that, but it was like watching a war movie from 1943. Simply like that. Coming close to concentration camps.’ The controversial concentration camp analogy is, therefore, not only used by impassioned outside critics, but also by people within the system.

Although these stories of compassion and concern can be understood as a form of narrative self-legitimation work in a system which suffers from acute deficits in legitimacy (Bosworth; Ugelvik ), we would like to suggest that they also do a more complex work which may merit further analytical attention. In our study, compassion was often expressed as a result of having a more direct and closer contact with human suffering, which led the officers not only to sympathise with migrants, but also to see them in a more positive way and as more trustworthy. One officer described:

You get a slightly different understanding, because you get so much closer to the person, the credibility of the person standing before you is much stronger. I have registered asylum seekers [in Norway] until I’m exhausted (…) All of them are saying the same. (…) While here, you do have real people standing in front of you, telling a trustworthy story (Police Officer, de-briefer, PU6).

Here, compassion may still have performative and self-legitimating aspects (not least in relation to the interviewers), yet it is also an emotion which arises due to the physical closeness to suffering, resembling ‘the living presence’ of the Other described by Emmanuel Levinas. This presence is experienced and is different from, and not reducible to, words and ideas. As one officer said: ‘you see the hopelessness in it. I have in a sense understood it for several years, but now I can see the reality of what they are talking about’ (PU4).

We would like to suggest that such sentiments of understanding, compassion and a wish to help, which arise from direct, on the ground human encounters (although related) should be distinguished from the performative aspects of humanitarianism visible particularly in political discourse and policy documents. They demand a more nuanced understanding of the meaning of humanitarianism within border studies and an acknowledgement of the ambivalent feelings and moral discomfort inherent in doing border work. This discomfort is dealt quite differently by individuals performing border control and is felt more acutely by some than others. Nevertheless, amplified by intense public critique, moral discomfort seems to be an inherent part of doing border control and can in some cases lead to outright resistance.

For example, our interviews with police officers performing border control in Norway demonstrated clear disagreement in how the police should use their newly acquired right to conduct border checks. Random territorial control of foreign citizens in the city center and targeted controls of families in detention centers were criticised for being immoral and inhumane. There was also a resentment of using deportation numbers as official performance targets for police work. The ‘us’ and ‘them’ divisions, which are frequently talked about in relation to migrants, were thus also created within the police force. As one officer from Oslo Police District described:

Well, it can be said that internally, within the police, there are different understandings of how to apply immigration law. It is just as well if this came out. Some look at this from an ethical perspective – that is us – while others are more concerned with performance targets and such. And the ethical side thinks that performance targets are a wrong way of doing the work, and admits that this is a sensitive field to work in, while it seems to me that the others, the other side, have not reflected on this well enough. I know that within the Police Immigration Unit there are disagreements as well.

Border studies have, so far, paid relatively scarce attention to such internal resistance and the moral and ethical discomfort of performing border control (see Bosworth for valuable exception). By seeing humanitarian rationalities primarily as a way of cementing and legitimising the status quo, we may be operating with a rather one-dimensional understanding of humanitarianism and failing to differentiate between different aspects and actors. While one of the main strengths of studies of humanitarianism has been to connect broad policy issues to questions of morality and emotion, this slippage may be also one of its main drawbacks due to the obscuring of on the ground inter-personal dynamics. Moreover, the field may be slow in recognising resistance, and potential for it, coming from within the system. Consequently, a question can be asked whether border studies may be poorly equipped to fully understand the dialectics of change arising from the moral discomfort of doing border work, as well as liable to reproduce its own ‘us’ and ‘them’ divisions.