The recent paper by Kristina Roepstorff and Kristoffer Lidén (Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies paper 12, 2023) exploring the concept of humanitarian mediation presents an important contribution to academic and policy discussions around the ethical questions of engagement with authorities that don’t share the worldview presented by the social and political discourse of the Global North. It provokes the call for a more courageous engagement with politics than current constructions of humanitarian action permit, which, as the paper observes, is “a short-term, needs oriented intervention that is guided by the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence in order to avoid the politicisation of aid and to guarantee access to the affected population” (p. 4).

Solidarity as a principled approach

My own research into the questions of access and identity in the contemporary environments of conflict and complex emergency indicates that the humanitarian sector needs to engage with a new discourse that extends beyond the principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence and which engages more confidently with its political identity. It directs towards the construction of a new humanitarian ‘space’ where the expression is one of solidarity with the most vulnerable, that legitimates engagement with politics and enables a constructive challenge to authority if clearly defined ‘red lines’ are crossed or compromised.

‘Solidarity’ as a principled approach is becoming more prevalent in the humanitarian lexicon, once kept firmly at a distance by many in the classical or ‘minimalist’ end of the aid-development spectrum, where the principle of neutrality was seen as inviolable. Solidarity indicates a degree of engagement with a political, racial, religious or ideological controversy – normally in support of the most vulnerable or those seen abused or denied of their human rights – and so requires a level of intellectual analysis that explains why this does not diminish the principle of neutrality, seen as the primary tool in the humanitarian identikit to permit access to all sides in a conflict. ‘Identity’ and ‘access’ are the common denominators that – once framed more universally in the discourse of politics and power – can enable the two approaches to work together.

A resolution of the equation directs towards a fresh discussion around the humanitarian identity – one that leans away from the exceptionalism that has framed debates over past decades and turns towards a common approach that engages a broader platform of stakeholder interests. This requires confident engagement with the political identity of humanitarian action that will gain access to the discursive space of power and authority and enable a voice that protects those excluded.

Charles Taylor observed that “common meanings are the basis of community” (1971, p. 30), meaning that a sense of community extends beyond intersubjective interpretations of language and reach towards identifying a world with shared reference-points, in which there is a collective purpose that gives rise to legitimated common actions, with shared meanings. In her formulations of the Capability Approach originally presented by Amartya Sen as a philosophical approach to guide work in the sector of international development, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum acknowledges the hierarchies and inequalities that form the structure of human existence. In her approach, the inviolable right is the entitlement to live with dignity and respect – the right to a life worth living. To protect this right in an unequal world means enabling a voice of solidarity and support to those excluded from the discussion.

Constructive challenge

The right to challenge authority and speak truth to power is a universal phenomenon, shared across history, religion and cultures. Shakespeare’s play ‘King Lear’ examines the dynamics of power and resistance and introduces the concept of the ‘fool’ as a figure for legitimated challenge to authority. European literature represents the medieval ‘sage-fool’ as being a figure of resistance within the exercise of power. Enid Welsford (1935) presents a comprehensive history of the ‘fool’ and outlines a common genealogy which stretches from Europe to the Islamic world. This gives evidence of a demand for popular access to a dissonant identity, able to question authority and raise a constructive challenge if it sees it deviating from the accepted norms of the community. In its contemporary expression, self-deprecating humour was common amongst Sarajevans and amongst citizens elsewhere in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the conflict 1992-95. These often featured the characters of Mujo, Suljo and Fata making jokes that reflected a humorous and critical analysis of that time. Modern analogies might be linked to the political lampooning through perceived foolishness in series like the Simpsons in the United States. An engagement with power is necessary for meaningful confrontation.

A space for convivial engagement

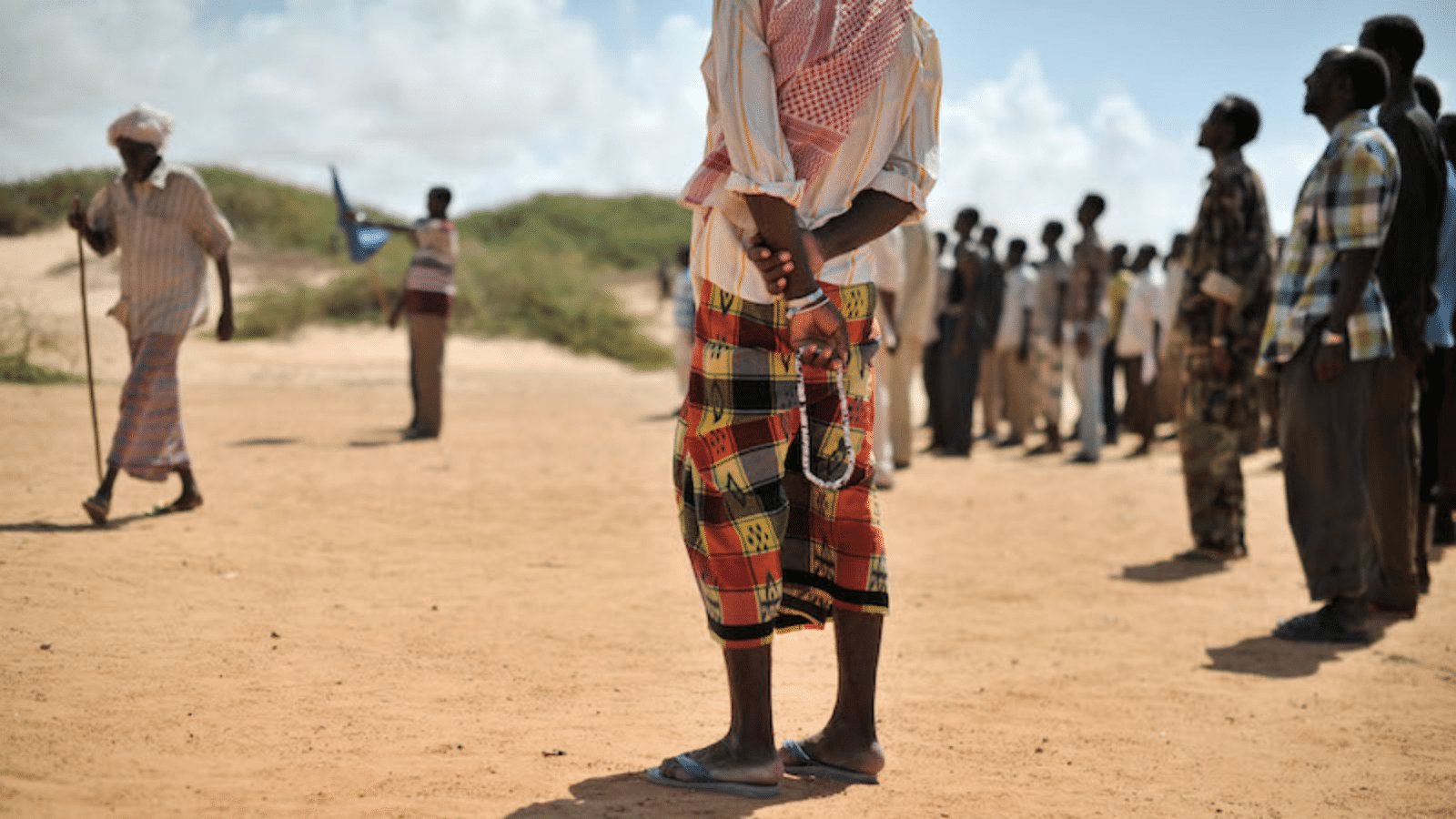

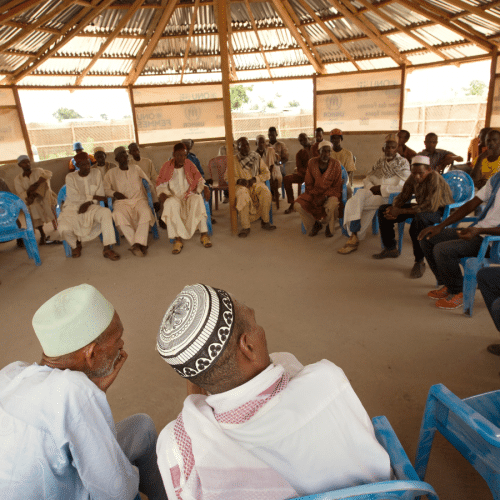

Meike de Goede’s and Francis Nyamnjoh’s works on relationships and power on the African continent urge a constructive engagement with the African continent by turning the lens away from the binary approaches that influence much of the aid and development discourse in the Global North. De Goede argues that recognition of diversity and engaging with the strength of a sharing and convivial society will enable a new approach to building relationships, seen not as a site of altercation but as “a site of interaction, where convivial agency occurs” (2015, p. 27). In Nyamnjoh’s study, he encapsulates this in the form of the Frontier African who inhabits and co-exists with others in the ‘uncertain peripheries’ of hierarchy and power. This is an identity of those who operate across frontiers and see the value of “a world where one can simultaneously belong and not belong” (2017, p. 260).

This space for discourse is a liminal space, where one can opt in or opt out. In my study on humanitarian identity, moral worth and popular legitimacy is reached along a path that emphasises ‘capabilities’ instead of ‘abilities’ and is not troubled by inequalities of endowment but insists on equality of access. This resembles the ‘convivial’ approach used by Nyamnjoh and de Goede that sees relationships as a site of interaction rather than altercation, where convivial agency occurs. Convivial interaction means recognition of complementarity not exceptionalism. I see this new space for discourse embodying and protecting the ‘Third Party’ which the NCHS paper mentioned earlier sees as an essential component for humanitarian mediation, able to engage the broadest platform of stakeholders (addressing the question of scale that the NCHS paper presents as a topic for further research, p. 9). I suggest that this will guide a new approach to principled humanitarianism, where the discourse will focus on the virtues of constructive engagement in an uncomfortable space, where the humanitarian can belong, yet not belong.

References

de Goede, M. (2015). Consuming Democracy: Local Agencies & Liberal Peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Leiden: African Studies Centre.

Gordon-Gibson, A. (2021). Humanitarians on the Frontier: Identity and Access along the Borders of Power. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Nyamnjoh, F. (2017). Incompleteness: Frontier Africa and the currency of conviviality. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 52(3), 53–270.

Taylor, C. (1971). Interpretation and the sciences of man. The Review of Metaphysics, 25(1).

Welsford, E. (1935). The Fool: His Social and Literary History. London: Faber and Faber.