Kristina Roepstorff is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) working on the research project, “Red lines and grey zones: Exploring the ethics of humanitarian negotiations” (RedLines).

Kristoffer Lidén is a Senior Researcher at PRIO and the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies. He currently leads the research projects “RedLines” and “On fair terms: The ethics of peace negotiations and mediation.”

Introduction

In contrast to ‘humanitarian negotiation’ (Clements, 2020; Grace, 2020), the practice of mediation in humanitarian action has so far received little attention. A look into the few available reports and texts reveals that mediation in humanitarian contexts is used for various purposes and takes very different forms. Sometimes humanitarian actors who negotiate for access and protection resort to a trusted third party to help them negotiate with counterparts with whom they cannot make direct contact.[1] In other instances, humanitarian actors themselves may function as a third party in conflicts that arise in humanitarian contexts and endanger the humanitarian response (Jenatsch, 1998) or to improve access and protection (Grimaud, 2023). Indeed, the International Committee of the Red Cross’ (ICRC) mandate allows the organisation to act as a mediator when it is necessary for humanitarian purposes (Lizzola, 2022: 2). Occasionally, humanitarian actors may also become more actively engaged in peace processes, blurring the lines between humanitarian action and peacemaking (Tabak, 2015).

Despite the various ways in which mediation plays a role in humanitarian action, the phenomenon is not well documented and hence not studied systematically. This may be due to a number of reasons. On the one hand, exploratory interviews with humanitarian practitioners point toward what Grace (2020: 17) in the realm of humanitarian negotiations has referred to as a cognisant gap: though humanitarian actors engage in mediation, they are not aware of it or don’t think of it that way.[2] Consequently, there is no reflection of the role that mediation plays in their work. On the other hand, being equated with peace processes, mediation may be considered beyond a humanitarian organisation’s mandate. If humanitarian practitioners find themselves in the role of a mediator, they may engage in mediation tacitly, purposefully not documenting mediation activities (Bala Akal, 2022 on tacit engagement). Of course, another explanation for the neglect of mediation as part of the humanitarian toolkit could be that mediation is not (yet) widely practiced in humanitarian action. Whatever the reason may be, its increasing promotion gives rise to several questions concerning its usefulness, applicability and ethical implications – all of which requires an inquiry into this phenomenon. Most significantly, and bearing in mind the diversity of mediation contexts outlined above, the concept of humanitarian mediation merits some conceptual attention, including a clarification of what qualifies as humanitarian mediation – and what does not.

Humanitarian mediation: What is in a name?

A rising number of specialised training programmes[3] and related job listings, for example with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC)[4], are indicative of a growing interest in, and use of mediation for humanitarian purposes. That the concept of humanitarian mediation has found its way into the work of various organisations is for instance exemplified by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue’s Humanitarian Mediation Program[5]. Thereby, the notion of humanitarian mediation is explicitly used to describe a process that is linked to, but is also distinct from negotiations. This begs the questions of how humanitarian mediation differs from humanitarian negotiations or other forms of mediation, and what its relationship to peace processes is. In short: where to draw the boundaries?

Mediation meets humanitarian negotiation

A good starting point for investigating the concept and practice of humanitarian mediation is to define mediation. Mediation, both in its domestic and international application, is a well-established field of research and professional practice. The wealth of literature on the topic has produced a number of different definitions that only diverge in minor ways, sharing some key components: namely, that it is a process in which a) a third party (the mediator), b) assists parties to a conflict c) finding mutually agreed solutions. Commonly, the mediator is understood as a neutral and impartial third party and the process of mediation to be voluntary, although these two qualifications have been subject to much and ongoing controversy (see for example De Girolamo, 2019; Crowe and Field, 2019; Zamir, 2010; Svensson, 2009; Hedeen, 2005; Field, 2000; Svensson and Lindgren, 2013; Touval, 1996; Smith, 1994; Wehr and Lederach, 1991; and Nelle, 1991).

A prominent definition proposed by Jacob Bercovitch, a leading scholar in the field of international (peace) mediation, incorporates these components but also offers a more detailed description of mediation as

“a process of conflict management, related to, but distinct from the parties’ own negotiations, where those in conflict seek the assistance of, or accept an offer of help from, an outsider (whether an individual, an organisation, a group, or a state) to change their perceptions or behaviour, and to do so without resorting to physical force or invoking the authority of law” (Bercovitch, 1997).

This definition links the process of mediation to the parties’ own negotiations. Yet, and though mediation can be understood as a form of assisted negotiation (Bercovitch, 2006), it is the presence of a third party that, as Simmel pointed out, fundamentally transforms bilateral negotiations, allowing for the resolution of conflicts were direct negotiations may have reached an impasse (Simmel, 1950 as cited in Palmer and Roberts, 1998: 101).

In the humanitarian sphere, negotiations are part and parcel of a humanitarian practitioner’s routine activities. Securing access and protection of people affected by conflict, natural hazard or displacement are among the biggest challenges that humanitarian actors face in their operations (Clements, 2020; Tronc, 2018). To do so, humanitarian actors negotiate with various counterparts for access, protection and other fundamentals for their humanitarian missions.[6] Negotiation skills are thus considered essential to humanitarian practitioners for being able to carry out their work (Grace, 2020). In situations in which the assistance by a third party transforms the negotiations into a mediation process, ideally, the affected population and relevant actors engage directly in a safe environment, abiding to mutually defined and accepted ground rules upheld by the mediator, who acts as a neutral and impartial facilitator of a process from which mutually acceptable solutions emerge (Grimaud, 2023). Thus, not only the presence of a third party, but also the process itself and the situations to which it lends itself differ in such ways that mediation cannot be reduced to negotiations.

The question remains, what then can qualify as humanitarian mediation? The term ‘humanitarian’ is commonly used in reference to the caring for people in dire need without regard to their identity or political affiliation. It also refers to the policy field of humanitarian action as part of ‘global governance.’ Humanitarian action describes the immediate life-saving activities in the midst of natural hazards, conflicts or displacement (Barnett and Weiss, 2011; Walker and Maxwell, 2009). It concentrates on the alleviating of suffering and maintaining of human dignity during and in the aftermath of crisis, as well as on the prevention and strengthening of preparedness and mitigation of such situations (Maxwell and Gelsdorf, 2019). In its ideal-typical form, humanitarian action is a short-term, needs-oriented intervention that is guided by the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence in order to avoid the politicisation of aid and to guarantee access to the affected population (Barnett and Weiss, 2011; Lieser, 2013). Very generally, it can thus be established that humanitarian mediation is a form of mediation that is linked to the field of humanitarian action and has a humanitarian objective, focusing on the caring for people in dire need to save lives and alleviate suffering.

Humanitarian mediation: Definition and application

Beyond this very general understanding of humanitarian mediation, the term has been concretised and conceptualised in different ways.

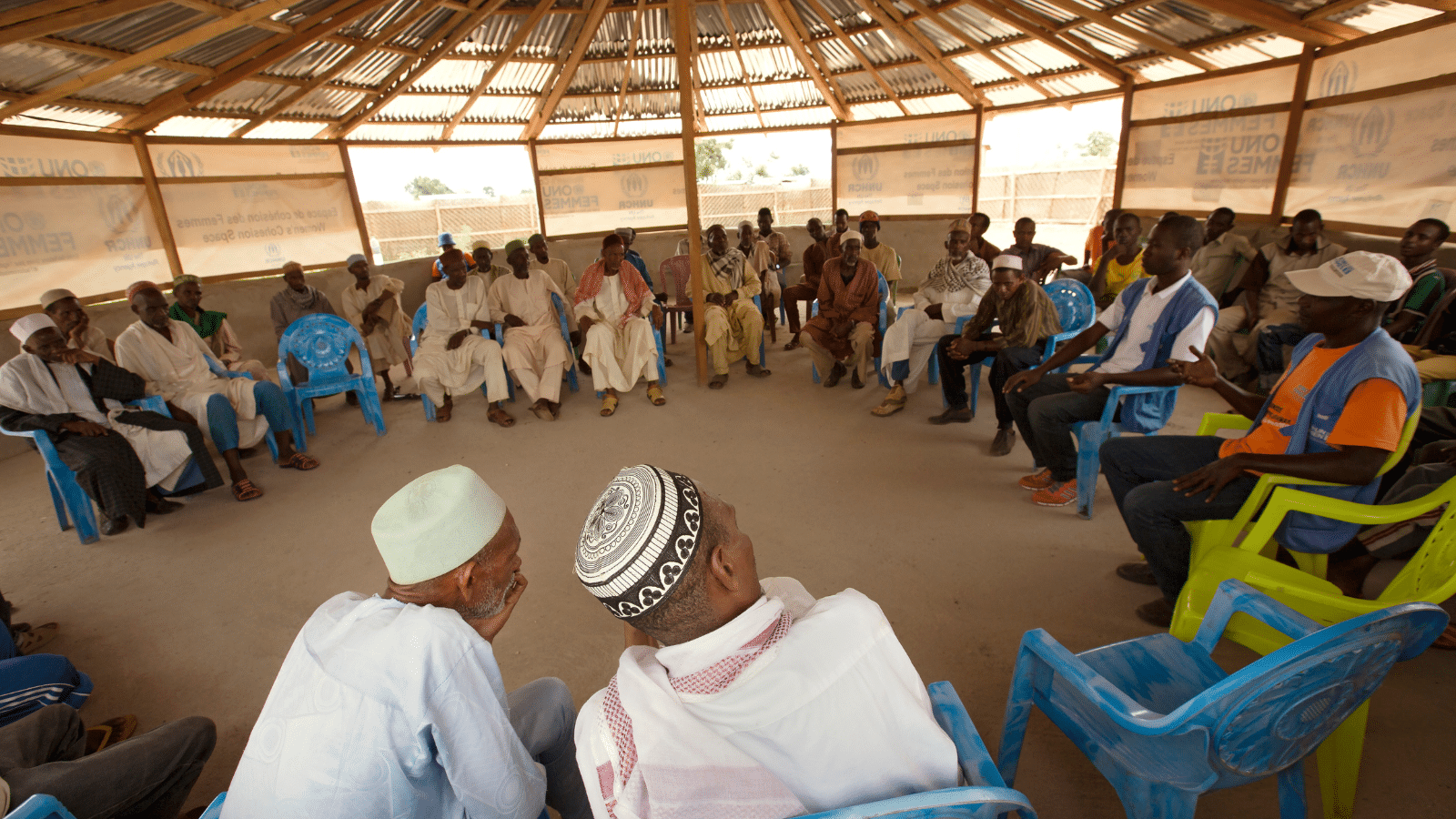

Merging the general definition of mediation with humanitarian action, the Humanitarian Mediation Network, for example, defines humanitarian mediation as “an inclusive and voluntary process addressing humanitarian concerns in emergency contexts in which a neutral and impartial humanitarian actor facilitates the communication and the collaboration between stakeholders involved in, and/or affected by conflicts, in order to assist them find, by themselves, a mutually acceptable solution.”[7] Another institution that offers trainings in humanitarian mediation, the Clingendael Institute, shares this understanding in both substance and actor – with one caveat. While it too holds that this field of mediation practice concerns humanitarian issues and involves at least one humanitarian actor, this does not necessarily need to be the mediator.[8] Moreover, it stresses the important role of local actors in mediating humanitarian negotiations between a humanitarian aid organisation and a group about humanitarian assistance. This description of humanitarian mediation again shows its relation to humanitarian negotiations, while the focus on local humanitarian mediators points to two topical themes in research and practice. First, it relates to the role of local actors in providing humanitarian assistance and protection and the humanitarian sector’s localisation agenda (Roepstorff, 2020). Second, it relates to the debate on the potentials and pitfalls of using insider mediators in mediation processes (Roepstorff and Bernhard, 2013; Mason, 2009; Svensson and Lindgren, 2013).

The key role of local actors as insider mediators is documented in a report by Search for Common Ground entitled “Community Mediation in Action: Improving Access for Humanitarian Aid”. The report illustrates how in Yemen a local conflict that threatened to block access for aid actors was resolved through inclusive and participatory mediation by insider mediators.[9] As another example[10] of the role of community mediation for humanitarian action in Moldova shows, it becomes difficult to differentiate general mediation from humanitarian mediation – risking conceptual vagueness. Moreover, both cases suggest an intertwining of humanitarian and peace efforts in humanitarian mediation.

The conceptualisation of humanitarian mediation as ultimately linked to peace processes is reiterated in a definition given by the Henry Dunant (HD) Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, which describes its humanitarian mediation activities as “enabling conflict parties to address key issues ranging from the protection of civilians and safe access for aid agencies to the special needs of women and children, displaced people and minority groups.” Thereby, humanitarian mediation is believed to complement and support peace efforts. This understanding of humanitarian mediation again stresses the humanitarian substance of this kind of mediation.[11] In contrast to the latter two definitions presented above it however entails a strong focus on conflict contexts, also highlighting the complementarity of humanitarian and peace mediation very much in line with the triple nexus approach (ICVA, 2018).[12]

Indeed, from the perspective of peacemakers, humanitarian access negotiations play a key role in peace processes (Lizzola, 2022) and humanitarian action is seen as contributing to the success of peace mediation efforts (Greig, 2021). However, humanitarian organisations are generally reluctant to be involved in such political processes, as this might jeopardise their neutrality and independence. There is thus often resistance to using humanitarian action as a tool in peace processes and many humanitarian organisations remain sceptical about the triple nexus approach – especially in the context of protracted conflict (Lizzola, 2022). Upholding a clear distinction between the peace and the humanitarian domain and emphasising their particular agendas and purposes, humanitarian mediation, when conceptualised as operating at the intersection of humanitarian and peace efforts, may consequently be viewed with suspicion and caution.

To sum up, existing definitions of humanitarian mediation diverge in the extent to which the mediator and/or parties to the process need to qualify as humanitarian or the extent to which the process is considered part of, or distinct from peace efforts. For analytical purposes, we thus suggest the following working definition of humanitarian mediation that focuses on humanitarian concerns and humanitarian settings, but that opens up to different kinds of mediators and stakeholders:

“a process in which a third party facilitates the negotiation between stakeholders facing a humanitarian problem, with the goal to assist them find a mutually acceptable solution.”

Humanitarian mediation is then a process that can occur at very different levels and scales, from the frontlines of the humanitarian response to diplomatic efforts, as well as at the intersection with peace processes, and in which a range of different actors may function as mediators.

With this definition, we avoid normative claims about the true meaning of humanitarianism and mediation to allow capturing associated practices in all their varieties. This means that any phenomenon that falls within this definition should be specified further in terms of what sort of problem and process it involves, and that the designation as humanitarian mediation should not be taken to mean that it is good or bad, right or wrong.

The practice of humanitarian mediation and the localisation agenda

No matter at which level humanitarian mediation occurs, the ongoing debate on localising humanitarian action is relevant for the practice of humanitarian mediation in at least three ways. First, and as established earlier, most of the times it is local actors that conduct the mediation and as such play a key role in the process.[13] Second, instead of negotiating on behalf of the affected community, in humanitarian mediation “community members themselves decide, for and by themselves, what is good for them” (Grimaud, 2023). This empowering aspect of mediation is very much in line with the Grand Bargain commitments that seek to shift the power to communities themselves. As such, and thirdly, it may also speak to the demands for decolonising humanitarian action, being a less “patronising” practice and process (Grimaud, 2023; Aloudat and Khan, 2022).

Indeed, local actors play a key role in providing humanitarian assistance and offering protection to the affected population.[14] Yet, they and the affected population remain notoriously marginalised in international humanitarian responses. To counter exclusionary practices, both a ‘participating revolution’ and the localisation of humanitarian action were invoked at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit. Under the Grand Bargain, powerful donors, UN agencies and INGOs committed to include people receiving aid in making the decisions that affect their lives, as well as making humanitarian action “as local as possible, as international as necessary” (IASC, 2023; Barbelet, 2018). Since then, the humanitarian sector’s localisation agenda has sought different ways to redress their continuing marginalisation in the international humanitarian response through reforms of humanitarian financing, partnership models and the general ways in which humanitarian action is carried out (Roepstorff, 2020).

The implementation of the localisation agenda, however, poses challenges that reverberate in the practice of humanitarian mediation. International attempts to localise humanitarian action and empower the affected population typically happen in settings with high degrees of social, economic and political conflict (Roepstorff, 2020; Melis and Apthorpe, 2019; Roborgh, 2020). Supporting one organisation might then fuel conflict or unwittingly empower certain actors at the expense of others, for example by propping up foreign-educated elites setting up local NGOs at the expense of public or traditional institutions (Roepstorff, 2022). This may both be an impediment to achieving their humanitarian objectives and entail negative side-effects for the affected communities, as becomes particularly apparent in forced migration settings where local humanitarian actors to a large extent represent the host, rather than the displaced community (Roepstorff, 2022; Pincock et al., 2021).

It may thus be necessary to anchor localised humanitarian action in agreements between the different humanitarian actors and affected communities, clarifying how the funding is to be distributed and for what purposes. In the model of humanitarian negotiations, such agreement would be forged through negotiations between a humanitarian agency and local stakeholders. Then, the humanitarian negotiator representing the agency would try to convince the interlocutors to accept a solution of their organisation’s liking. With humanitarian mediation, however, the local stakeholders would be expected to advance their own solutions – involving international humanitarian organisations as ‘service providers’ or not. Sometimes, international organisations with a local presence might be part of the negotiations, but only on a par with the other local parties. The mediator and their team could provide the parties with information on the problem and potential solutions, but it would be up to the parties to sort out how this should be done (Grimaud, 2023). This would require letting go of, or at least sharing and/or shifting, power – something that dominant international actors such as donors, INGOs and UN agencies are rather unwilling to do (Grimaud, 2023; Baguios, 2021; Kergoat, 2020).

Against the backdrop of the localisation agenda, funding agencies might thus make mediation a requirement where needed, offering financial incentives for local actors to engage in such mediation processes. Such mediation would not necessarily happen at a high political level. So far, mediation typically takes place in local communities or in specific sectors or ‘clusters’ like health services or camp management.[15] It is of course also possible to envision more formalised mediation mechanisms to facilitate high-level humanitarian negotiations between international organisations and local political authorities – but this is not really where current mediation practices seem to come from. In any event, this would not only entail a significant need for mediation capacity and support from humanitarian organisations or dedicated mediation agencies – be they international or domestic – but also call into question the voluntariness of the process. Promoting such an approach presents several aspects for consideration, including ethical questions that arise.

Ethical implications of humanitarian mediation

As explored by our ongoing research project, humanitarian negotiations involve a range of ethical challenges and dilemmas. [16] These partly stem from engagement with interlocutors that put humanitarian workers at risk, disregard the humanitarian principles or cause the humanitarian problems in the first place. However, ethical problems also come from the biases, hierarchies and adverse effects of the humanitarian work itself. By explicitly relying on the norms and perspectives of local actors, humanitarian mediation may be a way of surpassing some of these ethical problems, and promises to be a more inclusive, participatory and culturally sensitive approach to solving humanitarian problems.

Meanwhile, mediation comes with its own ethical challenges. Depending on the level and context in which the mediation occurs, different ethical issues may emerge at diplomatic levels or at the frontlines of humanitarian responses. As outlined earlier, humanitarian mediation is predominantly linked to processes at the community level, or at ‘the frontlines’ so to speak. It is for this very reason that one of the few documents explicitly dealing with ethics in humanitarian mediation, the Humanitarian Mediation Network’s reference guide for trainings, focuses on this level. Offering a broad list of “ethics and principles of neutral and impartial mediation”, it suggests norms that to a large part refer to the concrete strategies and tools that mediators use in the process (Grimaud, 2023; HPN, 2017).[17]

These principles overlap with general professional principles guiding the work of mediators in other domains. Though these professional principles may differ in detail, they generally include the principles of impartiality, neutrality, voluntarily, autonomy, informed consent and the avoidance of conflict of interest (Roberts, 2014; Otis and Rousseau-Saine, 2014; Ignat, 2019; Hopt and Steffek, 2013; Kastner, 2021; UN Guidance for Effective Mediation, 2012). Adhering to the principles of mediation in settings of humanitarian emergencies might be highly demanding, considering the time aspect and pressure to act quickly to save lives and mitigate suffering. Indeed, it should be kept in mind that mediation is a process that requires time and thus may not be the most suitable approach for time-critical humanitarian action.[18]

In situations where humanitarian actors are a party to the conflict, the ethical dilemmas and red lines are likely to be the same as the ones identified in relation to humanitarian negotiations. Having said that, the very nature of the mediation process may give rise to particular dilemmas even in such cases, for example when it comes to the question of accepting a certain actor as mediator. It seems to be, however, the situations where humanitarian actors take up the role of mediator themselves that need particular consideration.

Ethical dilemmas will most likely stem from a conflict of interest resulting from the divergent professional roles and mandates. For instance, humanitarian practitioners that mediate may see ways of helping people in desperate need that the parties do not agree with. They may then find themselves in a difficult position to accept the parties’ own solutions when perceiving them as contradicting with established humanitarian practices and standards or going against their respective organisational policies.

Mediation may also most likely occur in environments that are deeply hierarchical and in which the humanitarian organisation as mediator may feel the need to empower marginalised groups excluded from the process. Indeed, the issue of power asymmetry and exclusion of certain groups from the mediation process is an ethical concern much discussed in the mediation literature (see for instance Lanz, 2011; Waldmann, 2011; Kew and John, 2008). Is there a moral obligation on the part of the mediator to level power asymmetries and address discrimination and marginalisation? This is a question that humanitarian organisations acting as mediators may well be confronted with and will need to take a stance on.

In other cases, mediators may find themselves personally favouring certain political actors while seeing others as the root of the problem. Remaining impartial and neutral in these settings might be seen as ethically problematic. Indeed, it is not given that mediation would be the right remedy under all circumstances, especially in those where atrocities and grave human rights violations are committed. On the other hand, humanitarian actors who work on the premise of the humanitarian principles may arguably make good mediators, being trained (and required) to stay neutral and impartial in challenging settings (Grimaud, 2023).

All these issues resonate with ethical dilemmas that have been described in the existing mediation literature (see for instance Bush, 1994; Otis and Rousseau-Saine, 2014; Waldmann, 2011). Yet, one might presume that these will rarely be as hard or consequential as when mediators enter the field of humanitarian action.

Conclusion and outlook

Considering the increasing promotion of humanitarian mediation, there is a clear need for better understanding of its practice and ethical implications. From the above conceptual discussion of humanitarian mediation and its different forms, several open questions and areas for further research can be identified:

- First, the question of scale: it needs to be clear at which level the humanitarian mediation happens (international, national, sub-national, community). This has implications for how it is conceptualised and practiced, including the expected role of the mediator and applicable normative frameworks.

- Second, for humanitarian mediation that takes place at the community level and the frontline of the humanitarian response, local actors are central. The exploration of humanitarian mediation must thus be linked to the broader debates on localisation and insider mediation.

- Third, a key question is how the traditional humanitarian principles apply in humanitarian mediation, and what principles mediators actually follow in different contexts.

- Fourth, and considering the demand for complementarity of mediation efforts in the UN Guidance of Effective Mediation and the ambitions of the triple nexus, the relationship between humanitarian mediation and (other forms of) political mediation, and the complementary role of peace and humanitarian mediation efforts need to be scrutinised.

Further discussion and analysis of humanitarian mediation and its ethical implications is thus urgently needed to allow for the further development of accountable and professional mediation practices in the humanitarian field.

The authors wish to thank Jerome Grimaud for sharing his expertise for this working paper, as well as to fellow members of the research project Red lines and grey zones: Exploring the ethics of humanitarian negotiations. The chapter draws on funding by the Research Council of Norway (grant number 325238).

Literature

Akal, A. B. (2022), Tacit engagement as a form of remote management: Risk aversity in the face of sanctions regimes, NCHS Paper. Oslo: Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies.

Aloudat, T. and Khan, T. (2022), “Decolonising humanitarianism or humanitarian aid?”, PLOS Global Public Health, 2(4).

Aneja, U. (2016), Bold reform or empty rhetoric? A critique of the world humanitarian summit. ORF Special Report.

Baguios, A. (2021), Localisation Re-imagined: Localising the sector vs supporting local solutions, available at: https://www.alnap.org/localisation-re-imagined-localising-the-sector-vs-supporting-local-solutions, last accessed 01.03.2023.

Barbelet, V. (2018), As local as possible, as international as necessary: understanding capacity and complementarity in humanitarian action, HPG working paper. London: ODI.

Barnett, M. and Weiss, T. (2011), Humanitarianism Contested: Where Angels Fear to Tread. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bercovitch, J. (2006), Mediation Success or Failure: a search for the elusive criteria. Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution, 7:289-302.

Bercovitch J. (1997), Mediation in International Conflict: An Overview of Theory – A Review of Practice. in Zartman and Rasmussen (eds.), Peacemaking in International Conflict: Methods and Techniques, Washington: USIP.

Bush, R. (1994), The Dilemmas of Mediation Practice: A study of ethical dilemmas in policy implications, Journal of Dispute Resolution, 1994 (1).

Clements, A.J. (2020), Humanitarian Negotiations with Armed Groups : The Frontlines of Diplomacy. Abingdon: Routledge.

Crowe, J. and Field, R. (2019), “The empty idea of mediator impartiality”, Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal [online], 29: 273-280.

De Girolamo, D. (2019), The Mediation Process: Challenges to Neutrality and the Delivery of Procedural Justice, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 39(4): 834–855.

Field, R. (2000), “Neutrality and power: Myths and reality”, ADR Bulletin, 3(1): 16-19.

Grace, R. (2020), The Humanitarian as Negotiator: Developing Capacity Across the Aid Sector. Negotiation Journal 36(1): 13-41.

Grimaud, J. (2023), Protecting civilians through humanitarian mediation, Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, London: HPN.

Hedeen, T. (2005), “Coercion and self-determination in court-connected mediation: All mediations are voluntary, but some are more voluntary than others”, Justice System Journal, 26(3): 273-291.

Hilhorst, D. and Jansen, B. (2010), “Humanitarian Space as Arena: A Perspective on the Everyday Politics of Aid”, Development and Change, 41(6): 1117–1139.

Hopt, K. and Steffek, F. (eds.) (2013), Mediation: Principles and Regulation in Comparative Perspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

IASC (2023), “The Grand Bargain in practice: How do humanitarian organisations ensure affected people are part of the decision-making?” https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-practice-how-do-humanitarian-organisations-ensure-affected-people-are-part-decision?, last accessed 16.03.2023.

Ignat, C. (2019), “The Principles of the Mediation Procedure”, Journal of Law and Public Administration, 10: 143-146.

Jenatsch, T. (1998), “The ICRC as a humanitarian mediator in the Colombian conflict: Possibilities and limits”, International Review of the Red Cross (1961 – 1997), 38(323), 303-318.

Kastner, P. (2021, ” Promoting Professionalism: A Normative Framework for Peace Mediation. In Catherine Turner and Martin Wählisch (eds.) Rethinking Peace Mediation, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Kergoat, A. et al. (2020), “The Power of Local Action: Learning and Exploring Possibilities for Local Humanitarian Leadership”. Oxfam.

Kew, D., and John, A.. (2008), Civil society and peace negotiations: Confronting exclusion, International Negotiation, 13(1): 11-36.

Kressel, K. (2006) Mediation Revisited, in Coleman P et al. (eds) The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice.

Lanz, D. (2011), “Who gets a seat at the table? A framework for understanding the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in peace negotiations”, International Negotiation, 16(2):275-295.

Lidén, K. and Jacobsen, EKU (2016), The local is everywhere: a postcolonial reassessment of cultural sensitivity in conflict governance. In: Burgess JP, Richmond OP and Samaddar R (eds) Cultures of Governance and Peace: a Comparison of EU and Indian Theoretical and Policy Approaches. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.132-149.

Lieser, J. (2007), “Zwischen Macht und Moral. Humanitäre Hilfe der Nichtregierungsorganisationen”, in: Rainer Treptow (ed.), Katastrophenhilfe und Humanitäre Hilfe. München: Reinhardt, 40–56.

Maxwell, D. and Gelsdorf, H. (2019), Understanding the Humanitarian World, Abingdon: Routledge.

Melis, S. and Apthorpe, R. (2020), “The Politics of the Multi-Local in Disaster Governance,” Politics and Governance, 8(4): 366-374.

Nelle, A. (1991), “Making mediation mandatory: A proposed framework”, Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol., 7: 287.

Network HM (2018), Humanitarian Mediation and Dialogue Facilitation. A reference guide for training participants.

Mason, S. (2009), Insider mediators: Exploring their key role in informal peace processes. ETH Zurich.

Otis, L. and Rousseau-Saine, C. (2014), The Mediator and Ethical Dilemmas: A proposed framework for reflection, Journal of Arbitration and Mediation, 45-47.

Palmer, M. and Roberts, S. (1998), Dispute Processes: ADR and the Primary Forms of Decision Making. London: Butterworths.

Pincock, K. et al. (2021), “The Rhetoric and Reality of Localisation: Refugee-Led Organisations in Humanitarian Governance”, Journal of Development Studies, 57(5): Pages 719-734.

Roberts, M. (2014), Mediation in Family Disputes. Principles of Practice, Farnham: Ashgate.

Robillard, S. et al. (2021), Localization: A “Landscape” Report. Feinstein International Center, Tufts University.

Roborgh, S. (2023), “Localisation in the balance: Syrian medical-humanitarian NGOs’ strategic engagement with the local and international”, Disasters, 47(2): 519−542.

Roepstorff, K. (2022), “Localisation requires trust: an interface perspective on the Rohingya response in Bangladesh”, Disasters, 46(3): 610-632.

Roepstorff, K. (2020), “A call for critical reflection on the localisation agenda in humanitarian action”. Third World Quarterly 41(2): 284-301.

Roepstorff, K. and Bernhard, A. (2013), “Insider Mediation in Peace Processes: an untapped resource?”, S+F, Security and Peace, 31(3): 163-169.

Smith, J. (1994), “Mediator Impartiality: Banishing the Chimera”, Journal of Peace Research, 31(4): 445–450.

Svensson, I. and Lindgren, M. (2013), “Peace from the inside: Exploring the role of the insider-partial mediator”, International Interactions, 39(5): 698-722.

Svensson, I. (2009), “Who Brings Which Peace?: Neutral versus Biased Mediation and Institutional Peace Arrangements in Civil Wars”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53(3): 446–469.

Tabak, H. (2015), “Broadening the nongovernmental humanitarian mission: the IHH and mediation”, Insight Turkey, 17(3): 199-222.

Touval, S. (1996), “Coercive mediation on the road to Dayton, International Negotiation, 1(3): 547-570.

Touval, S. (1995) Ethical dilemmas in international mediation. Negotiation Journal, 11(4): 333-337.

Tronc, E. (2018), “The humanitarian imperative: compromises and prospects in protracted conflicts”, Passways to Peace and Security, 1(54), available at: https://www.imemo.ru/files/File/magazines/puty_miru/2018/01/03_Tronc.pdf.

Waldman, E. (2011), Mediation Ethics: Cases and Commentaries, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Walker, P. and D. Maxwell (2005), Shaping the Humanitarian World. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wehr, P. and Lederach, J.P. (1991), “Mediating conflict in central America”, Journal of Peace Research, 28(1): 85-98.

Zamir, R. (2010), “The disempowering relationship between mediator neutrality and judicial impartiality: Toward a new mediation ethic”, Pepp. Disp. Resol. LJ, 11: 467.

Footnotes

[1] See https://frontline-negotiations.org/events/humanitarian-mediation-and-understanding-non-state-armed-groups/, last accessed 27.2.2023.

[2] Informal discussion with humanitarian practitioner, 5.12.2023.

[3] See the trainings offered in Humanitarian Mediation by Clingendael (https://www.clingendael.org/news/first-online-humanitarian-mediation-training) or the NOHA Network(https://nohanet.org/uploads/news/75/downloads/2018%20Training%20on%20Humanitarian%20Mediation%20NOHA%20-%20Information.pdf), last accessed 17.03.2023.

[4] See for example https://www.unjobnet.org/jobs/detail/37375960, https://ngojobsinafrica.com/job/humanitarian-mediation-officer/, or https://www.devex.com/jobs/humanitarian-mediation-project-manager-700330, last accessed 17.03.2023.

[5] See https://hdcentre.org/area-work/humanitarian-mediation/, last accessed 01.03.2023.

[6] Different definitions of humanitarian negotiations have been proposed from organisations such as UNOCHA, CCHN and HD and scholars researching on the topic (see for example Clements, 2020 or Grace, 2020). Though the proposed definitions share a common understanding of the process of negotiation, they differ in the extent to which they limit it to situations of armed conflicts or the definition of humanitarian actor and humanitarian objectives.

[7] Humanitarian Mediation Network, Humanitarian Mediation and Dialogue Facilitation. A reference guide for training participants, 2018.

[8] https://www.clingendael.org/news/first-online-humanitarian-mediation-training, last accessed 3.11.2022.

[9] See: https://www.sfcg.org/community-mediation-in-action-improving-access-for-humanitarian-aid/, last accessed 2.11.2022.

[10] https://unsdg.un.org/latest/stories/kindness-and-honesty-local-community-mediators-promote-roma-inclusion-moldova, last accessed 4.11.2022.

[11] HD Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, https://hdcentre.org/area-work/humanitarian-mediation/, last accessed 3.11.2022.

[12] For an overview on the Triple Nexus Approach, see ICVA, What is the Triple Nexus, 2018.

[13] https://www.clingendael.org/news/first-online-humanitarian-mediation-training, last accessed 3.11.2022.

[14] The important role of local actors was prominently acknowledged in the 2015 World Disaster Report, see: https://ifrc-media.org/interactive/world-disasters-report-2015/, last accessed 16.03.2023, but also emphasised in the regional consultations in preparation of the World Humanitarian Summit that was held in Istanbul 2016 (see Aneja 2016:7, Robillard et al. 2021: 12). Here a word of caution is in order: it remains unclear, who these ‘local’ actors are and there is a tendency to reduce the local in binary opposition to the international as a generalised non-liberal, non-Western, non-modern or non-humanitarian ‘other’ (Roepstorff 2020, Lidén and Jacobsen 2016). A critical localism is suggested here to allow for analyses of the construction of the local in particular humanitarian arenas (Roepstorff 2020, Hilhorst and Jansen 2010).

[15] See Humanitarian Mediation Network, Humanitarian Mediation and Dialogue Facilitation. A reference guide for training participants, 2018.

[16] The project Red lines and grey zones: Exploring the ethics of humanitarian negotiation (2022-2025) is hosted by Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in association with the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies, and led by Kristoffer Lidén, in collaboration with Kristina Roepstorff as the deputy project leader. It includes research partners from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá; Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu; University College Dublin; Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict, University of Oxford; and Inland Norway University. See: https://www.prio.org/projects/1938.

[17] These are: support without advising; question without evaluating; understand without endorsing; frame without influencing; listen: hear, look, feel; share the process, verify, validate; promote inclusion and participation; reaffirm your role, engage the parties; feel the pulse, be in the moment; build and generate trust.

[18] Explorative interview with humanitarian practitioners, 29.08.2022.