On a recent hot summer Friday afternoon, we found ourselves in front of our respective screens, greeting a group of anthropology students at the University of Vienna. It was warm there too, but most of the students had shown up for what was the last class of the semester. Anthropologist Leonardo Schiocchet had invited us to talk about our new initiative EURPET – the attempted catchy acronym for the more elaborate ‘European- Ukrainian refugee pets: Emerging trends’, which examines the reception and care of Ukrainian refugee companion animals in Norway.

Being asked to share ongoing research with students is always a great opportunity, we get to share our initial findings, gauge their reactions and learn from their perspectives. The week before, a boat had capsized outside Greece killing hundreds of refugees and other migrants from Pakistan, Syria, Egypt, Palestine and Afghanistan. The circumstances and media coverage of this tragedy stood in stark contrast to the massive rescue operation and media frenzy surrounding a missing tourist submarine at the Titanic wreckage site. This morally charged discrepancy also reignited debates around humanitarian discrimination or racism. As Schiocchet invited the class to engage, several hands shot up in the air. One student said she felt it was ‘morbid’ to think about animals’ legal status when this is not extended to all humans. Another student described it as ‘not fair’ to bring animals into the discussion. To her, it was self-evident that the 700 people drowning in the Mediterranean ‘deserved more attention’ than pets.

The conception of the EURPET project

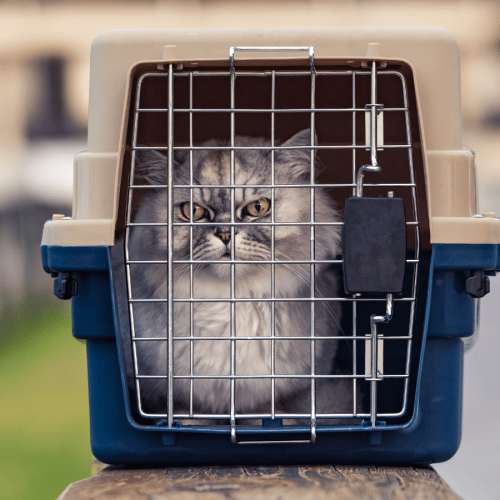

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the EU introduced a temporary protection scheme for those fleeing. As a mass influx of refugees began, something unusual happened: refugees arrived with their cats and dogs and, in some instances, with more unusual and exotic pets. Across the EU, national animal regulations were modified and civil society mobilised to care for the arriving refugee pets.

It was against this backdrop that EURPET was conceived. The initiative involves the two of us, Kristin Sandvik as a jurist and socio-legal scholar and Heidi Mogstad as an anthropologist, and an advisory board consisting of criminologists, political scientists and lawyers from the University of Oslo, OsloMet, the Chr. Michelsen Institute and the University of Bergen. Building on Sandvik’s 2022 scoping study of ‘pet exceptionalism’, EURPET takes an ethnographic approach to study the reception and care of Ukrainian refugee companion animals in Norway.

In the project, we study public, private and volunteer-based actors involved in the care and reception of Ukrainian companion animals and the various mechanisms, regulations and resources that have been developed and mobilised. As of June 2023, we have interviewed activists, veterinarians and civil society actors, and observed and engaged with government officials, bureaucrats and humanitarian workers and scholars. Using digital ethnography, we have followed Facebook groups and networks established to raise funds and awareness, exchange information and encourage aid, foster homes or adoption of Ukrainian companion animals. We have also filed access to information requests and done regular scoping of media coverage in national and local newspapers.

While the generous approach to Ukrainian pets initially seemed new and radical, our observations indicate that it was driven largely by pragmatic state concerns with smuggling and biosecurity. As the Russia-Ukraine conflict has raged on, Ukrainian companion animals have been protected because of their relationship with their human owners, not as legal subjects with independent rights for protection.

Complex tensions and ethical issues

Among our interlocutors, there were different views on this. Many were firm in their conviction that human refugees should be prioritised, while others were concerned about rabies and other health risks to citizens and animals in Norway. Others hoped that refugees from all countries would be allowed to bring their animals in the future. A few volunteers and activists expressed a more radical take on the animal-human binary: they maintained that human beings are ‘only one of many species’ and therefore do not deserve special treatment. However, others said they wanted to help animals in or from Ukraine because human refugees are cared for by others. Some also described this as a false binary, providing concrete examples of how their efforts to help animals benefitted humans too. One volunteer considered her effort to help animals from Ukraine as part of a larger project to move beyond the Anthropocene in the context of climate change and biodiversity loss.

In most of the interviews we have conducted so far, the complex tensions and ethical issues noted by the students are also evident. Our informants reflected on the need for a more ethical relationship between animals and humans while also being deeply concerned with the different value afforded to different groups of people. Although some of this concern took the form of increasing skepticism of Ukrainian refugees and their demands, most of the reflections represented attempts to reconcile the difficult situation of the Ukrainians and the heroic effort they carry out at home and in exile, with the reality that other groups do not have the same opportunity to self-protect.

Dilemmas in refugee management

Going back to the Friday anthropology class in Vienna, the students’ poignant comments and astute observations point to some of the key dilemmas in contemporary refugee management and how the old trope of being ‘treated worse than animals’ acquired a new meaning as the temporary humanitarian protection scheme for Ukrainians incorporated companion animals. As the conversation veered towards the larger questions of fairness and justice and what the Ukraine pet policy can tell us about hierarchies of life and suffering, we also discussed how the protection and reception of Ukrainian pets is shaped by class, racial and gendered dynamics. For instance, not everyone can afford to bring their pets or have the opportunity to do so in a global mobility regime that has produced such differential access to cross-border mobility. One student noted that even if you start your journey with a pet, it might disappear, get sick or die in the course of the flight.

what the Ukraine pet policy can tell us about hierarchies of life and suffering

We explained that in our research, we have also observed that animals can have affective and ‘humanising’ power. As one of our interlocutors speculated, seeing Ukrainian refugees bringing and caring for their pets might have heightened Norwegian citizens’ empathy for Ukrainian refugees and strengthened the perception that they are more ‘like us’ than refugees from other countries who are denied this opportunity. However, the logic might also work the other way. Might it be because we recognise Ukrainians as full human subjects with biographical life and attachments to other living creatures that we have accepted that they bring their animals regardless of the costs and risks this might impose on our society?

Finally, we reflected with the students about how the discourse surrounding the need to help and rescue Ukrainian animals is deeply gendered. In many ways, it also mirrors what the French anthropologist Didier Fassin famously described as ‘humanitarian reason’. Animals are framed as especially vulnerable, helpless and in need of saving. Like children, they are also represented as innocent victims of a war they did not choose nor understand. It is also worth highlighting that not all animals are deemed worthy of rescue and protection. Those who are prioritised usually have clear gendered characteristics: dependent, submissive to humans and relatively small and cute.

Two hours is never enough, the class drew to a close and we had to say our goodbyes. For the students we engaged with, it was clear there were many issues to discuss further and that moral dilemmas concerning humanitarian aid are relevant, acute and painful for them as global citizens. Paradoxically, in contrast to the emotional reactions and astute analyses offered by the students, 16 months of Ukrainian pet exceptionalism has fostered almost no critical debate in the Norwegian public. From the perspective of EURPET, this absence of debate and reflection will constitute an important point of inquiry as we move forward with the project.

The end of pet exceptionalism

At the same time, we will also continue to track legal developments and our informants’ initiatives. While finalising this post, the EU announced it would lift the regulatory exemptions allowing refugees fleeing Ukraine to bring their pets to Norway and the EU, and return to normal import requirements from 1 July 2023. This also applies to Norway. Sixteen months into the war in Ukraine, Norway’s period of pet exceptionalism has thus come to an end.

During the period of our research, some activists and animal charities limited their engagement with Ukrainian companion animals due to resource constraints, burn-out or competing priorities, however others have kept going. Many of them were shocked and dismayed by the news the legal exceptions would be lifted and now fear the consequences for both the animals and the humans who love them.

EURPET is hosted by the Norwegian Network for Animal Law at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law at the University of Oslo.