Problematising the subject of humanitarian protection

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, European countries have welcomed millions of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the brutality of the war.

This swift and compassionate response is both warranted and encouraging. Yet, ten months into the conflict it is worth reflecting on the moral dilemmas engendered by this response, namely that the exceptional willingness to welcome Ukrainian refugees does not merely reflect geopolitical concerns (Russia as a common threat) and realities (Ukrainians’ visa freedom, European solidarity, etc.), but should also be read in part as an expression of humanitarian racism.

While making this case is beyond the scope of this intervention, it is crucial to note that humanitarian racism is not only expressed in blunt and obvious forms or episodes (as when non-white students in Ukraine were prevented from crossing the border into Poland), nor is it merely a case of individual attitudes or dispositions. Conversely, humanitarian racism is a cultural and structural phenomenon that comes in many forms and expressions, including resistance towards mixing cultures and religions.

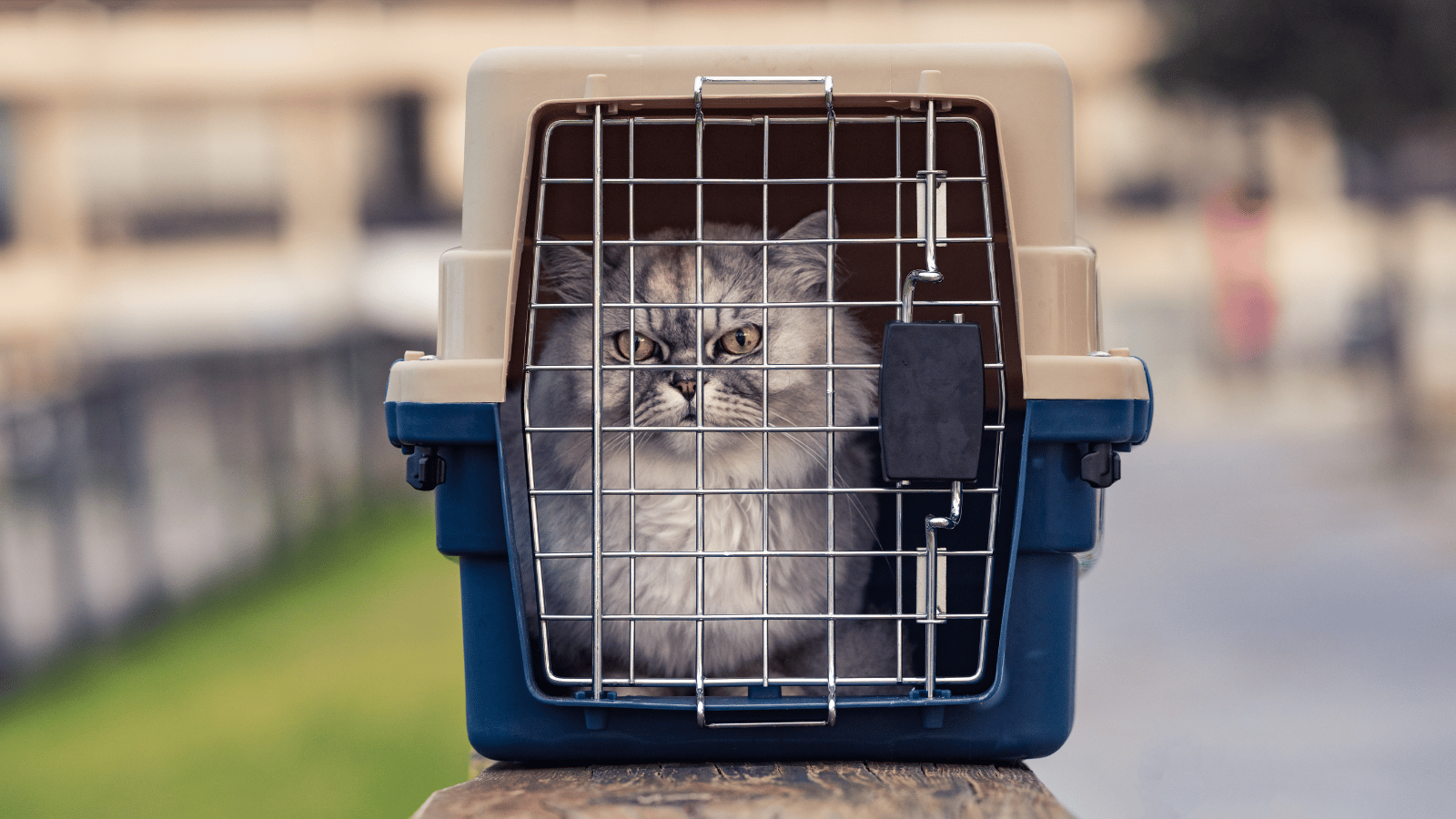

In this context, the “open-door policy” to Ukrainian pets” must be problematised. Not only are Ukrainian refugees treated as more worthy of protection than refugees from the Middle East and Africa; it seems like their pets are too! This begs a deeply uncomfortable question: given the historical and colonial tendency to conflate non-white people with animality, might Ukrainian pets be considered more human than the refugees trapped in prison-like camps (cages) at the European border? Arguably, the “pet exceptionalism” Sandvik identifies in the article linked above also challenges us to rethink and reimagine the subject of humanitarian protection.

On humanitarian racism

I have previously done research on humanitarianism and border politics in Greece and Norway respectively. In April 2022, I travelled with colleagues and a small film crew to Medyka, the busiest border crossing between Poland and Ukraine. Tired and cold, Ukrainian refugees waited patiently to cross the border into Poland. Some carried large bags or suitcases, presumably containing their most valuable belongings – and their pets. I saw dozens of cats, ferrets and dogs accompanying their owners on leashes or in crates and carriers. As Sandvik notes, the issue of pets (I treat my dog as a family member) risks “eating” critical thinking. As I observed the line moving forward, I was happy to see these pets being brought to safety. Yet, this also provided a stark reminder of all the times I had heard refugees on the Greek islands asserting that they were treated “worse than animals”. A letter written by two self-organised refugee groups on Lesvos in December 2020, addressed to all Europeans and Ursula von Leyen, contains the following poignant message:

“Many times, we have read and heard that we must live like animals in these camps, but we think it is not true. We have studied the laws to protect animals in Europe and discovered that they have more rights than us.[…] So we honestly ask you: Would we be treated like this if we were animals? We have decided just to ask you to grant us the simple rights animals have. We will be happy if we receive them and promise you will hear no more complaints from us.”

Back in Norway, observing the attention and resources devoted to caring for quarantined Ukrainian pets before reuniting them with their owners made me think about refugee friends and acquaintances who were denied family reunification. How did this look from their perspective?

Certainly, the accommodation of Ukrainian companion animals does not necessarily mean that animals are considered more human or valuable than refugees from the Global South. In her contribution, Sandvik argues that the care for pets has been largely driven by pragmatic biosecurity considerations. Following this logic, the reception of Ukrainian pets is a human and state-centric measure to minimise potential harm to national citizens. It is also important to note that the Ukrainian companion animals were not protected as animals with intrinsic rights and value but as pets, that is, as property of or companions to human beings. As Pallister-Wilkins argues, the protection of Ukrainian pets thus “(re)produce[s] hierarchical binaries of humans and animals, where animal subjecthood, life and well-being are conditioned by and through their relationships to humans.” I will add to these insights by suggesting that the reception of Ukrainian pets was accepted and supported by European societies because Ukrainian pet owners were recognised as full human beings with “biographic lives” and attachments to other living creatures. Refugees from other regions are rarely accorded this recognition, but rather are dehumanised or framed as threats to European ways of life.

Reflections

The extraordinary willingness of European states to receive and assume responsibility for Ukrainian companion animals has foregrounded difficult questions about what and whose lives should be protected. As Judith Butler argues, these questions are intimately linked with the question of whose lives are considered grievable and thus valuable and liveable in the first place. They are also related to personal and political questions of whom we want to share our lives with, as neighbours, citizens or companions.

Several friends and colleagues engaged in humanitarian work or research have found the Ukrainian “pet exceptionalism” uncomfortable and upsetting. However, this does not automatically make one opposed to moves to protect animals in war or grant them new rights. On the contrary, fighting racism and speciesism should be considered part of the same struggle to challenge racist and Eurocentric conceptualisation of the human and expand the subject of humanitarian care.

Arguably, the Ukrainian “pet exceptionalism” not only challenges us to expand the subject of humanitarian protection but invites us to rethink it altogether. As exemplified by Ukrainian refugees’ unwillingness to leave their pets, actual human beings correspond poorly with the autonomous and individualised subject of liberal discourse and refugee law. Conversely, most of us are deeply attached to other living creatures (human beings, animals, plants, land, etc.) to whom we carry our own obligations. How might recognising this change humanitarian work and protection? Moreover, can we design laws and policies that take some of these attachments and obligations into account?