People have probably always held humanitarian negotiations in human history as they have asked and argued for the right to help people in war, disaster and epidemics. In 2004, a how-to manual from the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue formally named and analysed the practice. This was followed by a second manual from OCHA in 2006 that focused on negotiating with armed groups.

A step change in the study and dissemination of good practice in humanitarian negotiation took place in 2016 with the creation of the multi-agency Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN) in Geneva and the publication of its large field manual on the subject in 2019. In the same period, scholars like Oliver Kaplan, Jana Krause and Emily Paddon Rhoades have examined how civilian communities negotiate directly for themselves, without professional humanitarian intermediaries, as they struggle for protection and assistance.

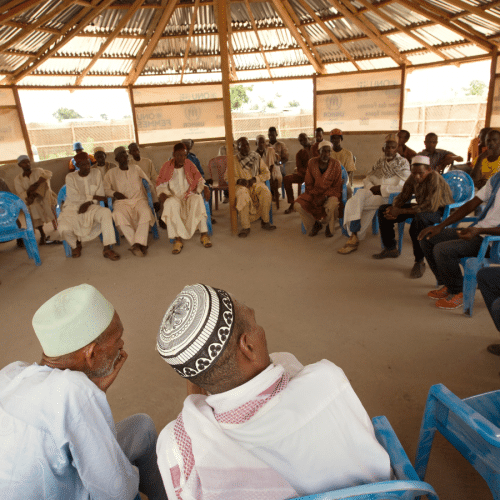

In October this year, the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies (NCHS) and the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) hosted a roundtable on the ethics of humanitarian negotiations, as part of a five-year study of the subject. Sitting in a room with 25 very experienced humanitarians and specialised academics describing and analysing their operational experience and research was a fascinating experience. Here are four main reflections on what I heard.

How do we perceive negotiations?

Throughout the two days it was hard to resist the temptation to see humanitarian negotiations in a simplistic adversarial frame, in which we often used the pronouns “us and them”. This frame carried an implicit grammar of this human encounter as a subject-object interaction in which we humanitarians are the subject and they (usually governments and armed groups) are the objects. We are talking to them.

But, of course, the reality is a conversation between two subjects, and the real challenge in philosophical jargon is one of inter-subjectivity. A good negotiation is a dialogue between two subjects. At all times, we must remember “they” are a subject with their own reasons, power and purpose. We have to take this seriously and enter into the famous POVO of peace studies – the “point of view of the other”.

So, every negotiation must try to break through the ritual and rigidity of a negotiation into a more insightful conversation. This is hard and probably impossible if only one side wants to do so. It requires careful listening and understanding between two subjects.

every negotiation must try to break through the ritual and rigidity of a negotiation into a more insightful conversation

Bubbling themes

A number of points kept bubbling up in our roundtable about which everyone agreed we must be very conscious.

Power – and usually an asymmetry of power – is integral to most humanitarian negotiations. Humanitarian disagreements are not just problems of miscommunication but problems with authorities who hold hard power over humanitarian objectives and have very different views of suffering and significant interests in obstructing humanitarian action. Around the negotiation itself, geopolitical forces and donor demands routinely exert hard power too.

Representation was a constant concern. It was raised in key questions. Who are we to be in the room? Who are we really representing? Who is left outside? Can we ever represent them? Should we focus more on humanitarian mediation to bring suffering communities directly into the room, and concentrate less on our humanitarian negotiations? There was also a frustration that the humanitarian sector is bad at collective negotiation: why do we not do this well as a sector and so build more negotiating power with others?

The question of local and international negotiators was also pressing. What is different, better and more difficult about insider and outsider negotiators? What is the value and experience of humanitarians from within the society in trouble and international negotiators from outside it? When is localising humanitarian negotiation simply cowardly “risk dumping” which endangers national staff, and when is it fair risk-sharing which carefully weighs the tactical pros and cons of playing an insider or an outsider in the lead role, and allows local people to struggle for their own rights and protection?

Compromise was inevitably a running theme. Achieving the humanitarian ideal is seldom realistic, so where should we set good enough grey lines and unacceptable red lines when we are trading off humanitarian principles and ambition? What constitutes a good compromise or a rotten compromise?

People were also honest about the significance of reputation and competition as a motivating factor in humanitarian negotiation. Agencies compete. This sometimes sees them going for a bad deal in order to be the first ones into an area, so boosting their reputation and getting the money, but can create a slippery slope for others that follow.

The frequent mismatch between preparation and reality in negotiations was widely felt. The carefully crafted game plan often collapses with the first real-time contact with the other side (as General von Moltke and Mike Tyson famously pointed out) and we are often bounced into improvising or deflected into negotiating things we had not anticipated.

The time involved in negotiation is a critical factor. Urgent one-off negotiations demand a certain quick thinking and instant rapport in which it is hard to avoid short-termism. More usual negotiation processes last for weeks, months and years and can be much more relational and incremental.

Finally, if we are good, we are never simply negotiating in one place. Negotiations should be happening simultaneously at the operational crunch point, in capitals, in regional organisations, in New York and Geneva, and in careful public diplomacy and communications. Most humanitarian negotiation needs to be multi-dimensional and multi-track, and effectively joined-up.

How rational is negotiation?

We often treat negotiation logically and rationally. For many of us this bias is hard to resist because of our very rational education and mindset. As a result, we spend most time when negotiating looking for rational patterns, thought processes and tools. We think too much.

But how much is negotiation really a rational and spoken process? We are wrong to misrepresent it simply as a “speech event” in which we think only about talking. Negotiation is a human activity like any other in which we are constantly sensing those around us, feeling the room, and picking up emotional cues and clues.

The roundtable often acknowledged that negotiation is just as much an emotional and unspoken process. Much – perhaps most – in a negotiation is non-verbal and heuristic. It turns on whether we like or dislike the other people, and they like or dislike us. Success hinges on whether we bond with our counterparts or feel blocked with them. The emotional sense of trust or distrust hovers everywhere around us, and all of us communicate not simply by the words we “give out” but the feelings that we “give off”.

negotiation is just as much an emotional and unspoken process

A major challenge, therefore, is to be more conscious of the chemistry and all that is unspoken but essential, and to work with it.

Recognising the tacit aspects of negotiation

Acknowledging the non-verbal is greatly helped by NCHS’s work by Aysa Bala Akal on what remains “tacit” or silent in negotiations. Important things that remain unsaid but not unknown are always part of our everyday human interactions. Our lives and calculations are full of things we fear to speak, or the silence we feel is wise to keep.

Every now and again in the roundtable, the spell broke and we saw various elephants roaming around the room. These were typically unspoken things that are completely non-negotiable, or things that are simply non-dilemmas or non-issues for one side. Or, they may be the tacit deals that are made with a nod and a wink, which work precisely because they are not spoken and acknowledged. Such tacit agreements are fragile and the worst thing would be to negotiate them. These “invisible lines” are profoundly important.

There is also the secret deal by one agency not told to others, and the “gold line” of organisational vested interest where agencies will compromise and stay purely to keep their funding and their jobs. A certain epistemic paradox is also tacitly at play in many situations: the knowledge that humanitarian aid and the humanitarian system is often part of the problem, while still determinedly negotiating for more of it.

Like the many challenges described above, which everyone openly acknowledges, the tacit and unspoken elements of humanitarian negotiations are also very important to own if negotiation strategy is ever to be truly ethical and honest.