This MidEast (PRIO) policy brief examines the flow of UN humanitarian aid to Syria, following the UN Security Council adoption of Resolution 2585 on 9 July 2021.

This PRIO blog looks at the unfolding humanitarian crisis on the Poland-Belarus border, which continues to claim several lives.

Tune in to hear about vulnerability and humanitarian disasters from the perspective of a humanitarian researcher and practitioner

The International Humanitarian Studies Association conference program is out now and the line-up features a few NCHS associates!

You can now view a recording of this discussion examining the argument for broadening the concept of accountability when it comes to humanitarian action

In this Bergen Global seminar, three of Sudan’s best-known academics and activists discuss migration into, through, and out of Sudan.

This Middle East Centre (PRIO) policy brief addresses the challenges for Syrian refugees in major host countries and their prospects for repatriation.

Interested to see how scenario building methods are used? Watch this webinar exploring digital innovation and humanitarian action using scenario building.

This CMI blog examines the impact of Europe’s externalization policies on the Middle East.

Welcome to “Talking Humanitarianism”, a podcast by the NCHS bringing you conversations with humanitarian researchers and practitioners.

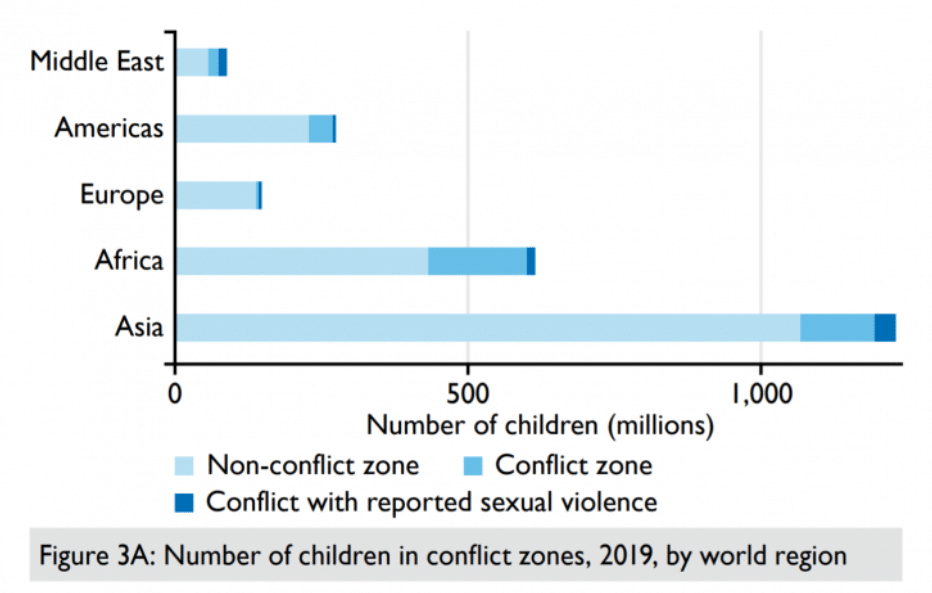

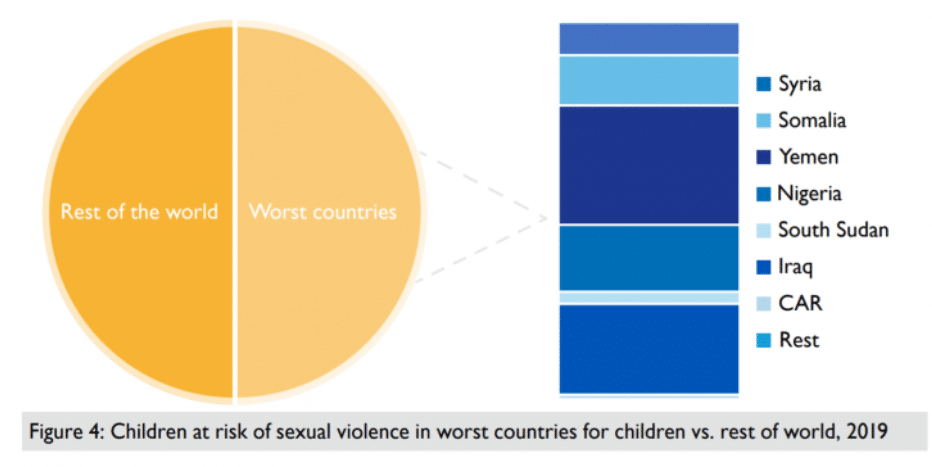

A staggering 72 million children—17% of the 426 million children living in conflict areas globally, or 1 in 6—are living near armed groups that have been reported to perpetrate sexual violence against children. That means 3% of all children in the world are living at risk for sexual violence in a conflict zone.

This is one of the figures of wartime risk reported in Save the Children’s 2021 report ‘Weapon of War: Sexual Violence Against Children in Conflict’. The figure is based on a new study conducted at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

concerning upward trend

This background study not only reveals an alarming reality, it identifies a concerning upward trend. This is a global problem that requires urgent attention. There are too few studies focusing on this problem or systematically documenting how children are victimized by sexual violence – directly or indirectly, how prevalent this is, and what the consequences are.

Globally, we estimate that in 2019 about 426 million children lived in a conflict zone, 50 kilometers or closer to violent conflict events. In some of these conflicts, the armed actors commit acts of sexual violence. A large majority of the conflicts with reports of sexual violence in recent years also have reports of children among the victims/survivors of sexual violence by armed actors.

The Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (SVAC) dataset provides systematic data on the reported prevalence of sexual violence, and which conflict actors have been reported to commit sexual violence against children. The updated SVAC data covers all armed conflicts in the years 1989-2019.

Due to data limitations we do not know exactly how many children have been victimised of sexual violence, only where it has been reported and how pervasive the problem seems to be. Based on this, and using specific information on the location and timing of conflict events and population density we estimate how many children live in areas where conflict actors commit sexual violence against children.

The figure of 72 million children reflects the specific risk associated with sexual violence by actors directly involved in armed conflict, and does not account for risk of sexual violence committed by other types of perpetrators, such as sexual violence by criminal gangs, peacekeepers, law enforcement, or domestic sexual violence.

Sexual violence against children is a global problem that requires urgent attention. Policy makers, human rights defenders, and other actors need to devote more resources and dedicated attention to this vulnerable group of war victims to reduce the harm of war to children.

Specifically, we offer three recommendations:

As the child population at risk of wartime sexual violence seems to be increasing, the imperative to take action is more urgent than ever. As a member of the UN Security Council, and chairing the working group on Children in Armed Conflict, Norway now has a golden opportunity to contribute to this end. The Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ine Eriksen Søreide, has promised to bring up the results from the report at the UN Security Council demanding that perpetrators of sexual violence in conflict be held accountable.