The 2020 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the World Food Programme (WFP) for “its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict”.

WFP is the world’s largest humanitarian organization, and food insecurity and food aid are much-discussed topics in humanitarian studies.

In this blog series, we examine the implications of the award and critically engage in debates on food (in)security, food aid, innovation and technology and the WFP as a humanitarian actor. This is the sixth post in the series.

Logistics of delivering food to people in need

Congratulations to the World Food Programme for receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020! Apart from the fundamental yet difficult relationship between hunger and peace, which has been problematised earlier, it is perhaps time to reflect just how WFP sees to it that food is being available, and/or delivered to people who need it.

logistically speaking, food is bulky

For a long time already, WFP logistics has had the mantra of “moving the world”. Their logistics and supply chain team is massive, not only in terms of numbers of vehicles and warehouses, but also when it comes to where these are located. Logistically speaking, food is bulky. In other words, it requires volume, capacity, and the related equipment. Given the volumes WFP needs to be able to move anywhere in the world, it is less surprising that they’ve built up their logistics capabilities, and have therefore also become the lead of the Logistics Cluster.

The “Log Cluster”, as it is often referred to, has an important coordination role to play if and when large volumes need to be delivered, and many organisations are involved. This is the case in larger sudden-onset disasters, but also after consecutive droughts, when regions and countries have run out of food altogether. The Log Cluster has though also come a long way in coordinating other global efforts in logistics and supply chain management, harmonising templates, contributing to global preparedness, writing a logistics operational guide (the “LOG”) to assist other organisations in their logistical efforts, assessing the logistics capacities of various countries etc. The list of initiatives is endless.

The link between food supply chains and peace

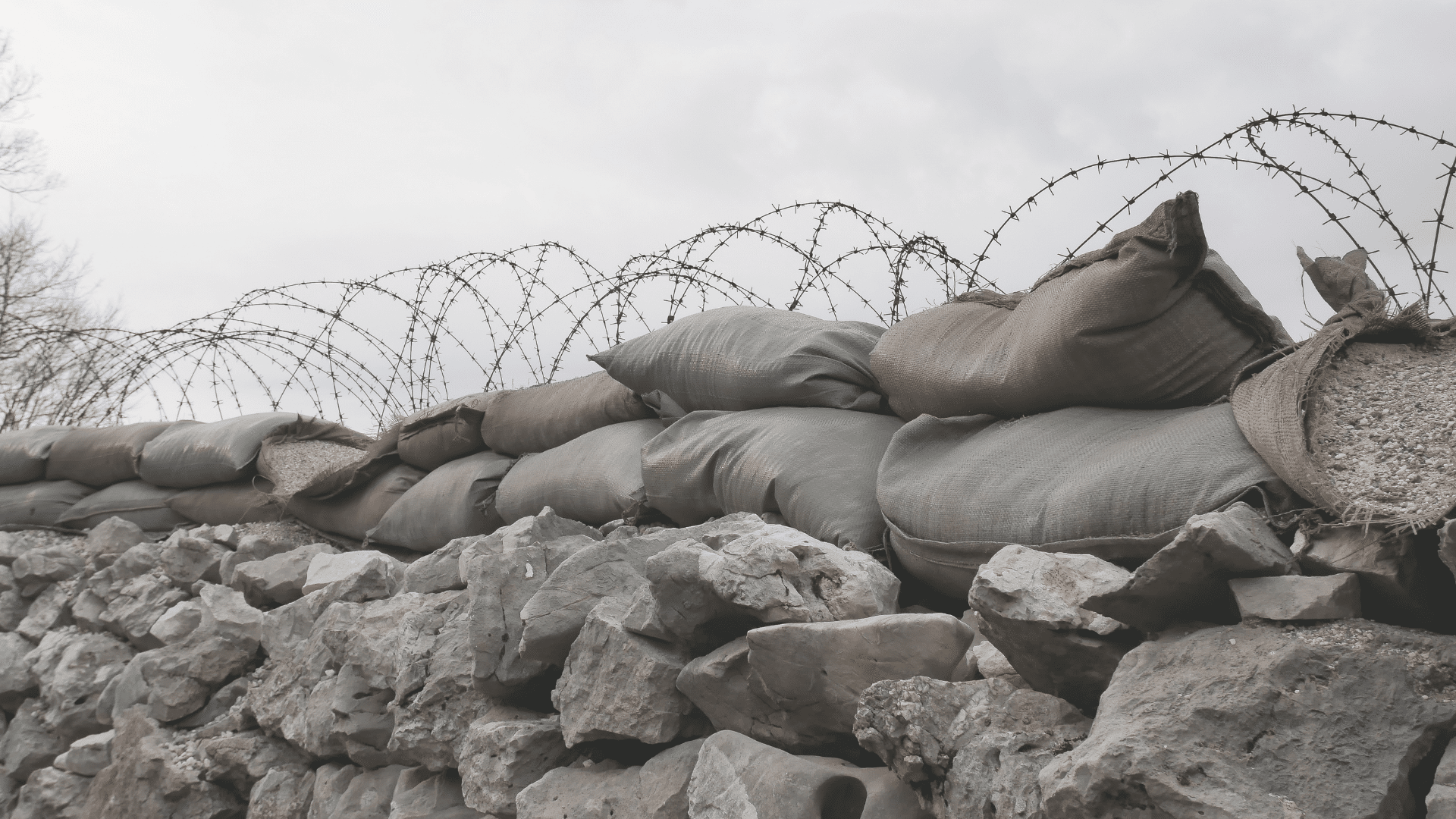

But what’s the link between food supply chains and peace? Food has been used as a weapon of war, as discussed earlier in this series. Delivering food to people who have been deprived of it, and negotiating humanitarian convoys to get secure passage is an important aspect. It is so important that “negotiation skills with warlords” is frequently noted as an eligibility criterion on job ads for humanitarian logisticians (Kovács and Tatham, 2010).

food has been used as a weapon of war

Furthermore, the way the supply chain is configured can reinstate interdependencies between conflicting parties. Creating, or reinstating interdependencies of traders and industries across conflict lines has been used as a peacebuilding mechanism already in the Balkans in the 1990s (Gibbs, 2009). In essence, the way (food) supply chains are designed can indeed contribute or undermine local capacities, but also contribute to conflicts or conversely, to peacebuilding.

Importing food and impact on local economies

Yet come to this, do we always need to move food, or any other in-kind goods for that matter? Food is a basic need, yes, but importing food can also undermine the local industry and economy. WFP engages in all sorts of innovation projects, from trying out new types of vehicles (amphibious vehicles, drones, trucks delivered by helicopters – some of which may be problematic in conflict zones to begin with, see “The good drone”), to fortifying local foods. Perhaps the most important innovation is though the combination of cash-based initiatives (CBI) with making food available through bringing (local) retailers closer, ensuring the availability as well as affordability of food.

The main selling proposition for CBI is that recipients can make their own decisions what they prioritise, and vote with their feet, or rather, their money. This is most certainly a very welcome development. From a supply chain perspective, they require a complete rethink, however (Heaslip et al., 2018). WFP and many other organisations have full-heartedly embraced CBI, with increasing percentages of their “deliveries” being ones in cash.

The next question will though be, how to ensure that food is in the markets also during the pandemic. At the end of the day, if everything else fails, humanitarian organisations will still need to deliver.