The 2020 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the World Food Programme (WFP) for “its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict”. WFP is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation, and food insecurity and food aid are much-discussed topics in humanitarian studies.

In this blog series, we examine the implications of the award and critically engage in debates on food (in)security, food aid, innovation and technology and the WFP as a humanitarian actor. This is the third post in the series.

The Nobel Peace Prize Committee signaled the critical importance of food when it announced that the world’s largest humanitarian agency, the World Food Programme (WFP), was this year’s winner for its role in combating hunger and, by extension, “bettering conditions for peace.” This is encouraging news but is it the full story?

Instrumentalisation of food aid

The prize brings to the fore the relationship between food – or lack thereof – and military strategies in contemporary armed conflict. The use of food as a weapon of war does not feature much in the discourse surrounding humanitarian action. At a time of diminishing multilateralism, the 2020 Peace Prize provides a useful opportunity to reflect on the growing need for humanitarian action given, in no small part, the flagrant disregard of fundamental humanitarian norms. Trucking in food tends to be the easy part. Helping ensure that hunger is not weaponized and that food aid is not used to advance political or military agendas is the real challenge. WFP now has a unique responsibility to invest in efforts that demonstrate that it is a worthy Nobel Laureate.

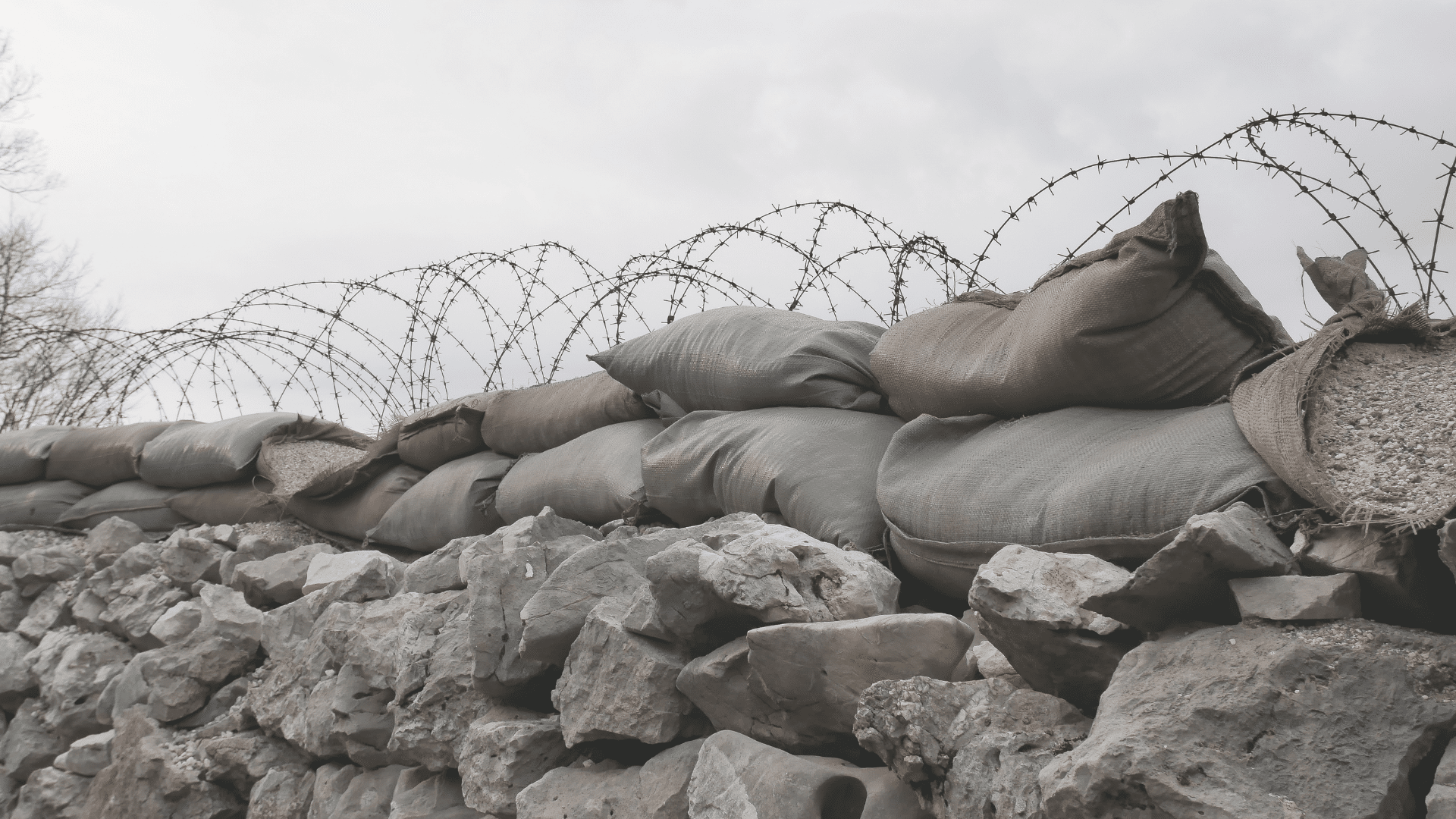

The recognition and acclaim inherent in the Nobel Peace prize is of particular importance in a time of frayed and failing multilateralism. The crossed vetoes of the Permanent Five (P5) in the UN Security Council (UNSC) effectively ensure that those in favor of war and the arms trade that sustains it – the P5 are among the world’s biggest arms dealers – effectively green-light atrocities. These include the deliberate starvation of civilians by blocking or bombing life-saving humanitarian food and other supplies, medieval-style sieges and embargoes that restrict or destroy the use of essential infrastructure such as ports and other means of transport. Inaction in the UNSC is tantamount to complicity in a trend where the weapons of choice on to-day’s battlefields include not just aerial bombardments and other explosive weapons but intentional starvation that disproportionately affects children, women and those who are already vulnerable. A study on Yemen, for example, found that “civilian areas and food supplies are being intentionally targeted.”[1]

Few will dispute that the WFP, and other agencies involved in tackling hunger in to-day’s war zones, other disaster settings and in situations of chronic malnutrition, poverty and deprivation, deserve the plaudits and the support needed to continue their vital work.

While the rationale for the Nobel prize acknowledges the significance of the relationship between hunger, armed conflict and peace, it is important to acknowledge the extent to which food insecurity, and efforts to address it, are weaponized in contemporary war settings. Although WFP is often at the forefront in negotiating access for food convoys, experience from Afghanistan to Yemen, including settings such as Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Sudan, South Sudan and Myanmar, shows that food assistance is routinely instrumentalised at great cost to those who are hungry.

A Prize with moral responsibility

Denying food to war-affected communities – deliberate starvation – as a method of warfare has, for this past century, been recognised as a war crime. The politics of such situations are, invariably, complex and complicated but it is incumbent on all stakeholders, including humanitarian entities such as the WFP that enjoys significant leverage, to challenge such practices and to do so in a meaningful and robust manner.

Similarly, WFP, in common with other relief actors, has a significant moral and institutional responsibility to address the deep-seated problem of transactional sex-for-food, an abomination that is routinely denounced but is a frequent reality in situations of humanitarian concern. WFP, like others, is committed to a zero-tolerance approach to the painful reality of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in the workplace, including in field operations, but this problem has persisted notwithstanding various reviews and the introduction of new policies and mechanisms.

The Nobel Peace prize should incentivise WFP to examine and strengthen its overall approach to the right to food including the protection dimension of humanitarian action. This necessitates going beyond the logistics of food convoys at which WFP excels. Otherwise, more instances of the “well fed dead” will occur. Priority attention must be given to the instrumentalisation and weaponization of food. WFP should strengthen its capacity to conduct conflict and contextual analysis that enables the development of strategies geared to avoiding harm to civilians and enhancing their protection. It must work collaboratively with others to head-off or address dangerous policies and practices that are antagonistic to food security and the safety and dignity of people in need.

otherwise more instances of the well fed dead will occur

Equally importantly, WFP should capitalise on its status as a Nobel Laureate to give meaningful effect to its declared zero-tolerance stance on sexual exploitation and abuse. This requires senior-level accountability and the establishment of an independent, external monitoring and investigative mechanism to put an end to a shameful history that is at odds with humanitarian values and the distinction of being a Nobel Peace prize holder.

Let the Nobel be an opportunity for everyone to re-affirm our faith in our collective humanity; this means challenging the inhumanity of armed conflict where deliberate starvation and other cruelties entail terrible human suffering, high death rates and growing numbers of people obliged to flee their homes to seek refuge and safety elsewhere.

References

[1] Is Intentional Starvation the Future of War? by Jane Ferguson, The New Yorker, 11 Jul 2018