An ‘absence of the state’ after the Beirut explosion

A reported 300,000 people were made homeless after the Beirut explosion on August 4, 2020, again reigniting the issue of displacement in Lebanon.[1] In the wake of the blast, civil society groups primarily led and organised the clean-up and the restoration of homes.[2] Meanwhile, many of the disaster displaced sheltered with family, friends, and relatives, in schools and public institutions, or at times, in hotels or other temporary shelters in Beirut and elsewhere.[3] Reflecting on the process a year later, one practitioner noted that the reliance on civil society was too great and that Beirut felt the “burden of the absence of the state.”[4]

According to the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, “national authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to IDPs (internally displaced persons) within their jurisdiction.” Since the 1970s, Lebanon established an expansive institutional infrastructure to deal with disasters, reconstruction, and displacement from man-made and natural disasters. Despite the dedication of budgets equal to multiple line ministries,[5] the Beirut blast indicated the fragility of Lebanon’s disaster response architecture, weakened by successive crises that struck after 2019.

This paper takes the opportunity to map and re-evaluate the structure of Lebanon’s disaster response institutions through analysing responses to displacement (long and short-term) of Lebanese citizens (as opposed to non-citizens). The paper argues that the Beirut blast is an opportunity to ‘build back better’ and overhaul the contemporary institutional arrangement that commodifies Lebanon’s displaced within a sectarian system of governance and is defined by unclear and overlapping mandates, mismanagement, and corruption.

Addressing displacement in Lebanon: the ‘war displaced’ and ‘the rest’

The Lebanese response to forced displacement consists of two frameworks: the first approach addresses ‘the civil war displaced’, i.e. Lebanese households displaced between 1975-1991. Whereas the second approach addresses displacement of citizens by conflicts and natural disasters after 1991.

Addressing the civil war displaced in Lebanon

The majority of academic and practitioner analysis of displacement in Lebanon focuses on civil war displacement due to its significance in post-conflict reconstruction; the high number of IDPs in Lebanon (22% of the country); and the central role of displacement policies and practices in securing the post-war settlement under Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri.[6] An estimated half a million to two million Lebanese were displaced between 1975 to 1990. Of these, around 450,000 to 600,000 remained displaced when conflicts ended in 1991.[7] Among this group, 75% lived in poverty.

The 1989 Taif Agreement established Lebanon’s post-war political settlement and provided for the return of the displaced to their villages of origin, an approach formalised in the UN-backed Ai’doon programme.[8] Return of the displaced was emphasised as a means of reversing confessional enclaving promoted by the conflict and was considered a requisite for national reconciliation.[9] The Ministry for Displacement was established in 1993 to implement the policy and facilitated return primarily through the payment of compensation of roughly $5,000-$7,000 per household; evicting squatters; and negotiating reconciliation agreements in areas impacted by sectarian cleansing, mostly in Mount Lebanon and the Chouf (see Tables 2 and 3).

The number of war-displaced in Lebanon dropped from 90,000 in 2009 to 7,000 in 2020.[10] By 2020, only 16,000 files remained with the Ministry for Displacement.[11] Nonetheless, the policy was largely considered a failure because most displaced households remained in their newly adopted communities. By the mid-1990s many households had lived in urban areas, especially Beirut, for over a decade building new attachments and raising families.[12] In comparison to the cities, rural areas lacked services and opportunities for employment.[13] Moreover, international agencies critiqued the return policy as misguided and failing to acknowledge rural-to-urban migration that would have occurred regardless of, although sped up by, the civil war.[14]

The implementation of the return policy was further hampered by gross mismanagement and corruption as the political parties transformed the disaster response architecture into personal and political fiefdoms. In the absence of legal definitions about who could be considered ‘displaced’ individual bureaucrats decided eligibility for compensation with inconsistent results. Decisions were also influenced by whether households were squatting at the time.[15] An economy of compensation emerged, encouraged by political elites seeking to funnel benefits to their supporters. As a result, institutions addressing displacement encouraged sectarianism.

Corruption was probable in the post-war period, but the extent to which it occurred was exacerbated by the sheer amount of money funnelled through the state for the purpose of addressing displacement amounting to L£2,070 billion (US$ 1.37 billion) between 1993-2004. By 2004, international funding for the return process dried up and by 2022, the Ministry for Displacement was still finalising its mandate stalled by a few dozen cases tied up in the Lebanese courts.

Addressing displacement events after 1991

Despite the prevalence of displacement in Lebanon after 1991 (see Table 1), there is no centralised policy addressing internal displacement in Lebanon after the post-Taif return policy, and the country has not followed the growing trend in conflict prone states and drafted the 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement into law.[16]

| Date |

Location |

Event name |

Estimated nr. of IDPS |

| July 1993 |

South Lebanon |

Operation Accountability/ 7-Day war |

300,000 |

| April 1996 |

Tyre and UNFIL area of operations |

Operation Grapes of Wrath/April War |

400,000 |

| July-August 2006 |

Lebanon (nationwide) |

34-day war |

256,000 to 1,000,000 |

| 2007 |

Nahr al-Barid camp |

Conflict with Fatah al-Islam |

27,000 to 31,400 Palestinians |

| Summer 2008 |

Beirut and Tripoli |

March 8/March 14 clashes |

Variable reports. A few thousand to 36,000 |

| 2013 |

Sidon |

Battle of Abra |

No reported number (damage to 1500 buildings) |

| August 2014 |

Arsal |

Battle of Arsal |

2,000 – 18,000 Syrians and Lebanese |

| September 2014 |

Tripoli |

Battle of Tabbeneh |

Variable reports. A few thousand to 42,000 (25,000 Alawis) |

| August 2020 |

Beirut |

Beirut explosion |

Reportedly 300,000 ‘homeless’, but more likely in the tens of thousands |

Table 1: Displacement events impacting over 4,000 people in Lebanon, 1990-2020 (compiled from media reporting by author).

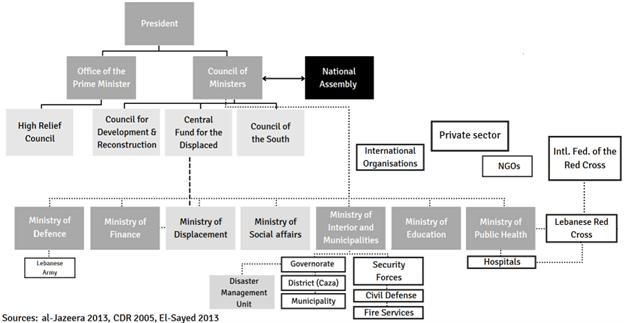

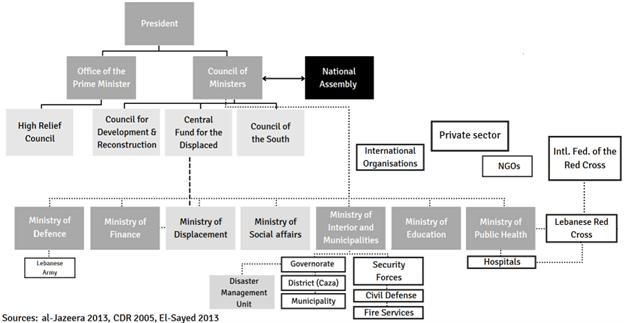

Rather, a constellation of state and non-state institutions and actors mobilise to address displacement incidents following emergency events including (in no particular order): the municipalities; the Lebanese Red Cross, the Lebanese Army, branches of the United Nations, various service ministries (education, social affairs, interior, etc.), NGOs and other international agencies (see Figure 1).[17]

Figure 1: Structure of Lebanon’s executive, the ‘Councils and Funds’, and line ministries that implement emergency and displacement response (light grey with black text by author).

A review of reporting, technical documents and interviews highlights the following practices by the above constellation of actors to address displacement: most contemporary displacement incidents are short term as opposed to protracted and there is considerable variation in the experiences and in the decision-making of individual households. It is often the working class that return to affected areas and urban informality poses a challenge during the compensation.[18]

In the short term, resources are mobilised to provide impromptu shelters and/or cover short term expenses. After displacement, return is encouraged through rehabilitation and clean-up efforts. In the medium term, the Lebanese state provides (to varying degrees, and sometimes not at all) for:

- Compensation for property damage

- Rehabilitation of properties

- Rehabilitation of infrastructure

- Provision of public services

- Provision of security (through reconciliation agreements/deploying the Lebanese Army or security services, cordons, etc.)

- Other projects addressing the displaced as a vulnerable group (development or psycho-social programming)

Compensation remains best practice internationally on the logic that affected individuals identify the most cost-efficient means of rehabilitating affected areas and a laissez-faire approach has been the main means of facilitating return of the displaced since the 1990s.[19] In Lebanon, however, this led to a prioritising of the built environment as a technical issue over human cost and any sustainable political solution. The compensation process after clashes in Tripoli between 2008-2014 was tainted by allegations of corruption and amounts distributed by the High Relief Council were often insufficient to cover damages.[20] On the macro-level, the strategy contributed to the degradation of the urban environment as buildings become mosaics with variable building quality across repairs.[21]

Addressing contemporary displacement through wartime compromises

From the municipalities to the ministries almost all levels of Lebanon’s government have a documented role in addressing the needs of IDPs. Displacement is a cross-cutting and complex emergency with long term repercussions and producing different needs among various groups across humanitarian sectors.

At the highest level, the ‘Councils and Funds’ (sometimes described as ‘super ministries’) have the greatest resources and mandate and are most prominent in addressing the fall-out of conflict and natural disasters in Lebanon. This is particularly the case for the High Relief Council, the Council of the South, and the Central Fund for Displaced.

Collectively, the ‘super ministries’ operate under branches of the executive without effective checks and balances. The lack of oversight of the super ministries is justified by the extraordinary aspect of displacement and emergency response, which requires rapid responses otherwise deadlocked if addressed through the ministries. Table 2 provides an overview of activities for each of the ‘Councils and Funds’, including the Ministry for Displacement operating in collaboration with the Central Fund for the Displaced (CFD). Table 3 provides a summary of activities by each council identified through news and technical reports.

|

Council of the South |

High Relief Council (HRC) |

Central Fund for the Displaced (CFD) and the Ministry for Displacement (MfD) |

| Est. |

1970 |

1977 |

1993 |

| Reason for establishment |

Formed in response to political agitation by the Shia Sheikh Musa al-Sadr after a lack of response from the Lebanese government following the Israeli invasion in 1967 |

Established with the limited purpose of coordinating first response and recovery operations and management of donations and grants. It has since evolved to be Lebanon’s main emergency response mechanism |

The CFD was established to regulate funding flows to the Council of the South and the MfD.[22] The MfD was established to implement the return of the displaced and as a concession to Walid Jumblatt in the post-war government |

| Relevant legislation |

– Decree no. 14649 (12 June 1970)

|

– Decision no. 1/35 (17 December 1976)

– Decree no. 22 (18 March 1977)

– Resolution 4/97 issued (January 1997) |

CFD:

– Law no. 193 (1 April 1993)

– Decree no. 3370 (2 April 1993)

– Decree no. 8672 amending Decree no. 3370 (27 June 1996)

MfD:

– Law no. 190 (1 April 1993)

– Law no. 333 (18 May 1994)

– Law no. 242 (7 August 2000)

– Law no. 361 (16 August 2001) |

| Oversight |

Council of Ministers |

Office of the Prime Minister |

Council of Ministers and Office of the Prime Minister. Since the early 2000s, the MfD also reports to the Ministry of Finance |

| Geographic area |

South Lebanon |

All of Lebanon (most active in coastal cities and North Lebanon) |

Mt Lebanon, the Chouf, Beirut, and North Lebanon |

| Political affiliation (reportedly) |

The ‘service arm’ of the Amal Party since 1985. Some inroads made by Hezbollah after mid-1990s |

Noted in 2013 as a “Beirut-Sunni monopoly”[23] but considered among most professional of the super ministries. Affiliation not noted in media reporting

since 2013 |

CFD: Traditionally affiliated with members of the Future Movement and allies of former-Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri

MfD: Ministry is linked to the minister in charge, most famously under Walid Jumblatt and the Progressive Socialist Party during the 1990s. Oscillated between political parties since 2004 |

Table 2: An overview of the ‘Councils and Funds’ and the Ministry of Displacement.

|

Council of the South (CoS) |

High Relief Council (HRC) |

Central Fund for the Displaced (CFD) and the Ministry of Displacement (MfD) |

| Activities (reported in news media) |

– provision and organisation of shelter and relief to impacted households

– provision of emergency welfare

– surveying impacted areas (done by volunteers, contracted companies, Lebanese army)

– provision of equipment to municipalities

– compensation for property damage from natural and manmade causes

– mitigating economic disaster through crop buy-ups

– organising and providing relief to disasters abroad (Morocco 2004; Sri Lanka 2004 and Haiti in 2010)

– production of statistics including displacement numbers and property damage

– coordination of aid from international donors

– filling relief gaps not covered by the ministries

– facilitation of property/infrastructure repairs (Nahr al-Barid camp, Ain Hilweh Camp, Abra)

– clean up after disasters (2006 war; storms in 2002, 2003, 2010, 2018; forest fires in 2007 and 2008)

– established a ‘forward operating room’ after the Beirut blast with the purpose of coordinating NGO responses |

– design, procurement and supervision of infrastructure repair and reconstruction including schools, water, electricity

– repair of homes impacted by conflict

– assistance to detainees in Israel and their families

– assistance to those released from Israel or al-Khiam prison

– assistance to families of persons killed by conflict (martyrs)

– assistance to families expelled from their homes in Lebanon by Israel or Israeli-backed militias after 1996

– covering cost of healthcare for those impacted by conflict

|

– social housing (Hariri Project, Tripoli)

– encouraging return

– funding for operationalisation of MfD

– rebuilding homes

– eviction of IDPs from private properties (with help from security services and army)

– negotiation between IDPs, landlords, developers and other actors

– compensation to the displaced

– repatriation of whole villages

– negotiation of reconciliation agreements in affected villages

– removal of rubble

– reconstruction of infrastructure and services

– rehabilitation of homes in affected areas

– renovation of heritage buildings and buildings of religious significance

|

| Overlapping responsibilities |

The CoS, CDR and HRC: Rehabilitation of infrastructure

The CoS, CDR and HRC: Rehabilitation of homes

The Cos, CDR and HRC: Provision and rehabilitation of services

The CoS and HRC: Provision of emergency welfare

The CoS, HRC and MfD: Payment of compensation for damage to property |

Table 3: Reported activities of ‘Councils and Funds’ (as opposed to mandates).

Since the 1990s, critics lambasted the ‘Councils and Funds’ as inefficient and mismanaged (resulting in dual work, wasted resources, and unclear or overlapping mandates). Moreover, the ‘Councils and Funds’ were accused and often proven to facilitate rampant corruption, as well as lacking oversight and independent auditing. The Ministry for Displacement was used to facilitate funds in return for votes as recently as 2018. This is particularly problematic considering these institutions have budgets exceeding multiple line ministries. In 2017, for instance, High Relief Council expenditures equalled the combined spending of six ministries (L£69.7 billion/US$46.2 million).[xxiv]

Box 1: The Council for Development and Reconstruction and displacement

The High Relief Council and Council of the South have considerable overlap in mandate with the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR). The CDR was created in 1977 to reconstruct the country after the first bout of the Lebanese civil war between 1975 and 1976. In the early 1990s, the CDR was reformed by Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri as a grants management body to delegate and organise international funds designated to reconstruction and infrastructure. The CDR is not an institution addressing Lebanon’s IDPs per se, but due to its pervasiveness in the field of reconstruction, the body has considerable impact on urban development in Lebanon and IDP self-settlement. The most notable example is the case of Beirut during the 1990s, where CDR policies contributed to the rapid expansion of the impoverished areas in the south of the city when the wartime displaced remained in Beirut but were excluded from affordable housing within Beirut Municipality.[25]

|

Council for Development and Reconstruction |

| Est. |

1977 |

| Reason for establishment |

Established as the main reconstruction authority due to limited powers of the then-Ministry of Public Works. Activities stalled between 1977 and 1992. Reactivated as a development body by Rafiq Hariri

|

| Relevant legislation |

– Legislative Decree no. 5 (31 January 31 1977)

– Legislative Decree no. 91-177 (1991)

– Law no. 247 (7 August 2000) |

| Oversight |

Council of Ministers |

| Geographic area |

All of Lebanon (less in the South) |

| Political affiliation (reportedly) |

Affiliated with members of the Future Movement and allies of former-Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri until 2005. Controlled by the Office of the Prime Minister

|

Table 4: An overview Council for Development and Reconstruction.

Obstacles to reforming the ‘Councils and Funds’

Despite widespread acknowledgement of weaknesses and a string of corruption scandals since the 1990s, the ‘backwards-looking’ ‘Councils and Funds’ remain active three decades after the war ended. The tenacity of these super ministries and their resistance to reform efforts relates to:

Political capture of the ‘Council and Funds’: During the 1990s, the disaster response architecture evolved to become the primary means of distributing state funding from political patrons to their clients. The Council of the South has the longest history of such stretching back to the politician Kamal al-Asaad in the 1970s before it was awarded to Nabih Berri in 1985 as a concession during the formation of wartime government. The lack of oversight provided to the Council of the South was used as a model by Walid Jumblatt when the Ministry for Displacement was created in 1993. It is an open secret that each of the super ministries are unduly connected to individuals, political parties, and confessional groups (see Table 2). Political figures thus have the ability to use their respective state concessions to posture to their constituencies. In a typical case in 2009, Nabih Berri responded to the attempt to withhold funding in the state budget for the Council of the South with thinly veiled sectarian rhetoric: “is it all about punishing the south and southerners?”[26] The ability for the ‘Councils and Funds’ to receive international donations has provided a means for foreign governments and organisations to support political factions through Lebanon’s state institutions. Considering these factors, reform threatens to limit access to state resources among political actors and is therefore resisted.

A confessional security dilemma: The affiliation of each of the institutions to a political patron has led to a security dilemma reinforcing confessional divisions within the state. The likelihood that Lebanon may fall victim to conflict or natural disaster means that corruption becomes an accepted facet in the super ministries considering that each group – Christian, Druze, Sunni, Shia – requires assurances of state support. Although most of the super ministries are not outwardly sectarian in their practices (there are varying degrees and statements often highlight unity[27]), a lack of trust in the state means that practices are likely to be interpreted through a sectarian lens regardless of intention. In one such example, the 2012 bombing in Achrafieh (mostly Christian) was dealt with in less than 48 hours, whereas the 2012 conflict damage in Tripoli (mostly Muslim) only received compensation following weeks of protests (this parallel was drawn by the residents of Tabbaneh).[28] In this environment, reform of the ‘Councils and Funds’ is re-framed as an attack on the safety net of each group and therefore resisted. It leads to the conclusion that reform of one, requires the reform of all.

A marketplace of compensation: Before 2019, crises involving displacement presented an opportunity among political actors to compete in relation to who can provide the most benefits to respective constituencies. In this sense, the ‘Councils and Funds’ were part of a marketplace for compensation alongside the political parties, civil society organisations, and often anonymous donors. The most blatant example related to compensation payments for property damage after the 2006 war, where Hezbollah was able to provide higher rates than the High Relief Council. However, there are multiple other examples of dual compensation schemes operating in parallel with the ‘Councils and Funds’, such as the $3,300-$6,600 provided to each household impacted by the 2012 Achrafieh bombing by Beirut Municipality, or additional compensation of $1,000 provided by the ‘Together We Heal the Wounds Campaign’ in Abra, Sidon in 2013. In August 2021, Hezbollah distributed sums between L£5 and L£30 million to families impacted by the Tliel explosion in Akkar.[29] Within this system, displaced households become commodified as political capital, but nonetheless accept the circumstance and will support the status quo in lieu of alternatives and the prevailing ‘security dilemma’ mentioned in the point above.

Flexible mandates: Broad and undefined mandates have seen the ‘Councils and Funds’ evolve and become reinvented in response to new crises and the personal preferences of individuals in power. This was particularly evident during the 2006 July War that re-framed the High Relief Council as a reconstruction agency (despite a recognised gap in expertise) and reinvigorated the Central Fund for the Displaced and the Ministry for Displacement (despite their fledgling status in 2005). The Council of the South, a largely irrelevant institution in the late 1990s, saw its budget double following the Israeli withdrawal in 2000, and was further revitalised after the 2006 conflict. In 2010, the Council of the South was reportedly the largest employer in South Lebanon. These institutions are thus able to absorb and channel substantial amounts of funding (often through foreign grants and loans) that are distributed through procurement, employment, and compensation payments, solidifying political divisions and clientelist links.[30]

Further justifications for the status quo: Two additional aspects are emphasised in justifying the continuation of the ‘Councils and Funds’:

- Cutting the red tape: In a 1999 interview, the director of the High Relief Council noted that, “The ministries need two months to do what we can do in a day”.[31] The need to avoid deadlock in the Council of Ministers or the Parliament and the potential for delays in the face of emergency continues as a primary argument for maintaining the super-ministry structure.

- Strategic positioning within communities: The other argument maintains, particularly in relation to the Council of the South, that such institutions are well positioned in respective communities and therefore able to identify particular needs.

Neither of these arguments hold much weight. In relation to cutting the red tape, responses to disaster and displacement by Tripoli Municipality in October 2014 or civil society after the Beirut blast in August 2020 highlight that other bodies can quickly step in when provided sufficient political and financial support as well as dedicated human resources. Close links with respective communities is also a double-edged argument considering such linkages are a product of strategic posturing (as a main employer, etc.). In both cases, alternatives can be established. For instance, early reform efforts during the 2010s attempted to instrumentalise the Disaster Management Unit under the Prime Minister’s Office including sub-units on the governorate level. According to an employee at the al-Fayhaa Union of Municipalities, the governorate-level Disaster Management Units have been implemented, although less information is available publicly on their capabilities or how they coordinate with existing institutions.

The need to build back better

Section four of the 2015-2030 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction focuses on the strategy to ‘build back better’ emphasising disasters as moments of rupture allowing for the improvement of future responses. Considering these commitments, the Beirut explosion and its aftermath, in addition to the upheaval of Lebanon’s financial system, represent both an opportunity and an obligation for the Lebanese government to re-evaluate contemporary disaster response management, policies addressing Lebanon’s IDPs, and address an archaic institutional infrastructure established as a product of wartime and post-war political dynamics.

Predominantly under the direction of the super ministries detailed above, Lebanon’s displaced are governed by a constellation of organisations within and outwith the state. The result is critical to Lebanon’s contemporary IDPs since the current institutional architecture addressing their needs is hamstrung by an unclear hierarchy and overlapping mandates.[32] For external actors, the lack of hierarchy among institutions has led to confusion among donors delaying response and reconstruction efforts.[33]

Some solutions are clearer than others. One practitioner noted that the files that remain open with the Ministry of Displacement can be transferred to a ‘department for the displaced’ within an appropriate ministry, such as the Ministry of Social Affairs. Attempts to transform the Minister for Displacement into a Ministry for Rural Development have been announced since 2014. Similarly, the Central Fund for the Displaced should finalise compensation payments within a set timeframe and transfer legacy projects – such as administration of the Hariri Project in Tripoli – to a public housing body.

There does not appear to be any current plan to reform Lebanon’s displacement and disaster management architecture. Nonetheless, any reform process relies on political compromise, made more difficult in the context of political schisms framed around the issue of responsibility for the 2020 explosion.

Footnotes

[1] Although it is widely reported and cited that 300,000 people were made homeless after the blast, this number is not clearly backed up by any comprehensive data. Rather, some NGO practitioners note that many among the affected decided to remain in their homes close to their personal belongings.

[2] According to an international shelter specialist managing clean-up, “we didn’t have any dealings with the Lebanese Government. We didn’t see them” (author’s interview, September 2021). Also, author’s interview, former official from Ministry for Displacement, Lebanon, March 2022.

[3] Grassroots networks and social media facilitated connections between the homeless and open beds, for instance, through #ourhomesareopen on Twitter.

[4] Speaker on first panel at “Recovering Amidst Crises, Beirut’s Port Blast One Year Later”, on August 12, 2021, Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut.

[5] Monthly Magazine, “Higher Relief Council spends as much as six ministries combined,” January 12, 2018, https://monthlymagazine.com/article-desc_4567_.

[6] See the excellent work by Reinoud Leenders and Aseel Sawalha.

[7] Robert Kasparian, André Beaudoin, and Sélim Abou, La population déplacée par la guerre au Liban, Comprendre le Moyen-Orient (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1995).

[8] Outlined in Kamal Feghali, ‘Return of the Displaced; Government Policy and Implementation Mechanism (sic)’ Paper for Dubai International Conference for Habitat II on ‘Best Practices’, 19-22 November 1995. DISP/a95/11, Beirut, The Lebanese Republic, Ministry of the Displaced.

[9] Souheil El-Masri, “Displacements and Reconstruction: The Case of West Beirut – Lebanon,” Disasters 13, no. 4 (1989): 334–44.

[10] OCHA, “Lebanon – Internally Displaced Persons,” Human Data Exchange v.1.53.3, 2020, https://data.humdata.org/dataset/idmc-idp-data-for-lebanon.

[11] Author’s interview, former official from the Ministry for Displacement, March 2022. Only 150 persons from the 16,000 open files were contactable due to the age of the files, possible migration, death, and other reasons.

[12] Aseel Sawalha, Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a Postwar Arab City (Austin: University of Texas, 2010), 115, 124.

[13] Majd Bou Majahid, “The Resumption of ‘No Return’ for the Christians of the Mountain… Outrageous Numbers and ‘Druze Being Displaced,’” Al-Nahar, April 16, 2017, https://www.annahar.com/arabic/article/570824-عودة-اللاعودة-لمسيحيي-الجبل-ارقام-فاضحة-والدروز-ينزحون.

[14] USCRI, “World Refugee Survey 1997 – Lebanon” (Washington D.C.: United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, 1997), https://www.refworld.org/publisher,USCRI,,LBN,3ae6a8b820,0.html.

[15] Reinoud Leenders, Spoils of Truce: Corruption and State-Building in Postwar Lebanon, 1st ed. (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2012), 118; Sawalha, Reconstructing Beirut, 113.

[16] IDMC, “Lebanon: Displaced Return amidst Growing Political Tension,” A Profile of the Internal Displacement Situation (Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, December 15, 2006), 13; IDMC, “Lebanon: Difficulties Continue for People Displaced by Successive Conflicts” (Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and Norwegian Refugee Council, September 28, 2009), 7.

[17] Mazen J. El Sayed, “Emergency Response to Mass Casualty Incidents in Lebanon,” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 7, no. 4 (2013): 433–38. For instance, a constellation including Tripoli Municipality, the political parties (particularly the Future Movement), the Lebanese Red Cross, the Lebanese Army, and UNICEF (among others) addressed IDPs during the September 2014 clashes in Tripoli. Author’s interview, former- employee at Tripoli Municipality, December 2021.

[18] Author’s interviews, families in Tabbaneh, Jabal Mohsen and Qubbeh, December 2021-March 2022.

[19] Author’s interview, shelter specialist with international NGO, September 2021.

[20] Author’s interviews, families in Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen, Tripoli, December 2021-March 2022.

[21] Author’s interview, senior member of the Lebanese Order of Architects and Engineers, April 2021.

[22] The division of labor between the MfD and the CFD is that the MfD organises the files for compensation and sends them to the CFD, it is then in the hands of the CFD to provide disbursement which is out of the hands of the MfD.

[23] The Daily Star, “Mikati Warns Bashir over Remarks on HRC Scandal,” November 11, 2013.

[24] Monthly Magazine, “Higher Relief Council spends as much as six ministries combined,” January 12, 2018, https://monthlymagazine.com/article-desc_4567_.

[25] Sawalha, Reconstructing Beirut.

[26] Therese Sfeir, “Berri Slams Refusal to Earmark South Funds,” The Daily Star, March 28, 2009, 12852 edition.

[27] “Berri Insists Southerners Have the Right to Compensation,” The Daily Star, March 29, 2009, 12853 edition.

[28] Alex Taylor, “Officials Respond with Funds, Surveys after Blast,” The Daily Star, October 23, 2012; Misbah al-Ali, “Tripoli Residents Protest over HRC Compensations,” The Daily Star, November 20, 2012.

[29] An action noted by a former-Future Movement Deputy as “a deceitful attempt to interfere in the area”. See Suzanne Baaklini and Michel Hallak. ‘Hezbollah distributes aid to the relates of the Akkar explosion much to the dismay of the Future Movement’, L’Orient Today, September 9, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1274252/hezbollah-distributes-aid-to-the-relatives-of-the-akkar-explosion-much-to-the-dismay-of-the-future-movement.html.

[30] A typical case is highlighted in accusations by Nabih Berri (of the CoS) that the High Relief Council should have thanked Syria and Iran for reconstruction donations after the 2006 War, for which the High Relief Council issued an apology (see “Berri Insists Southerners Have the Right to Compensation,” The Daily Star, March 29, 2009, 12853 edition).

[31] Warren Singh-Bartlett, “What If It Were to Happen Here? The Death Toll in Turkey’s Earthquake Has Passed 14,000, with Thousands More Bodies Still under the Rubble,” The Daily Star, August 30, 1999.

[32] Mazen J. El Sayed, “Emergency Response to Mass Casualty Incidents in Lebanon,” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 7, no. 4 (2013): 433–38.

[33] Lysandra Ohrstrom, “Donors Demand Reconstruction Master Plan,” The Daily Star, September 21, 2006.

Robert Forster is a Doctoral Researcher at the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) on the project, ‘Urban Displacement, Development and Donor Policies in the Middle East’.

Writing took place partially during a research fellowship with the Institut français du Proche-Orient (ifpo) in Beirut. The author wishes to thank N. Sax for comments on earlier drafts and A. Rule for review of the final draft.

This paper is supported by the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies Research Network on Humanitarian Efforts dynamic seed funding initiative, funded by the Research Council of Norway.

Suggested citation: Forster, Robert. 2022 Building back better: The politicisation of disaster and displacement response architecture in Lebanon’, NCHS Paper 08 August. Bergen: Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies, pp. 1-14.