Environmental justice for refugees in host countries

A part one in a feature series on the environment-displacement nexus, this blog examines how Syrian refugees are disproportionately harmed by air and water pollution in Lebanon.

With the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly known as COP27, underway in Eygpt, the NCHS is featuring a series of blogs from the Prioritizing the Displacement-Environment Nexus (DENx blog, based at the Chr. Michelsen Institute). This is the third and final blog in the series.

Displaced individuals and communities, such as internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, are often marginalised within their host communities (Pollock et al., 2019). Marginalised populations have been presumed to be highly vulnerable to disasters (Lejano, Rahman, and Kabir, 2020). Here, disasters are understood as the societal damages, losses and disruptions triggered by the event of a natural hazard occurrence, such as a cyclone (Wisner, Gaillard, and Kelman, 2012). Yet the literature on displaced populations’ vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards is currently sparse, with shortcomings of data on evaluating the relationship between refugees and the environment (Van Den Hoek, Wrathall, and Friedrich, 2021) as well as natural hazards. This is of concern as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that there were 82.4 million forcibly displaced people in 2020 (UNHCR, 2020). This number is anticipated to continue rising with an increase in the number of and complexity of crises (Oliver-Smith, 2018).

From the current relevant body of literature (including climate change, migration, refugee, and socio-ecological studies), it is evident that the relationship between migrants and the environment and natural hazards is neither a linear nor simple one (Collins, 2013). Rather it is a complex relationship which is multifaceted. Evaluating environmental and natural hazard risk with spatial mapping and modelling does offer an initial layer of understanding, however, other elements need to be further considered and integrated, such as knowledge and practices, for more effective disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies (Hyvärinen and Vos, 2015). Hence, decisions, planning, and policies regarding refugees and the environment and hazards cannot be made homogeneously or applied using a one-size-fits-all approach (Collins, 2013) – and research needs to reflect this. There is currently a research and evidence-based gap in how refugees and IDPs interact with the natural environment and hazard risks in their newly settled areas.

Within DRR literature, there is strong advocacy for the inclusion of the local community in disaster planning and response as well as a stronger focus on community resilience (Hyvärinen and Vos, 2015). This is also reflected in one of the Priorities of Action from The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 is:

“To ensure the use of traditional, indigenous and local knowledge and practices, as appropriate, to complement scientific knowledge in disaster risk assessment and the development and implementation of policies, strategies, plans and programmes.” (UNDRR, 2022, p. 14)

The role of traditional, local, and indigenous knowledge has received increased attention in DRR, climate change, humanitarian, and other discourses. There is a consensus that local knowledge and practices are more successful, as they have community ownership and are contextually appropriate, and their role has shown to be a cornerstone of successful disaster management strategies (Martin, 2005). However, it appears that there is an assumption that individuals and communities are knowledgeable and familiar with the ecological and natural hazard processes of their physical surroundings when such ‘knowledge’ is called to be included in risk assessments and disaster prevention planning. This can lead to the following questions: How do refugees ‘acquire knowledge’ of the environment and natural hazards in their settlement areas? How does migrant knowledge fit within local knowledge and practices? It is not clear how displaced people fit into this discourse. To date, this has received little research and there are relatively few DRR strategies which are inclusive of displaced people (Zaman et al., 2020).

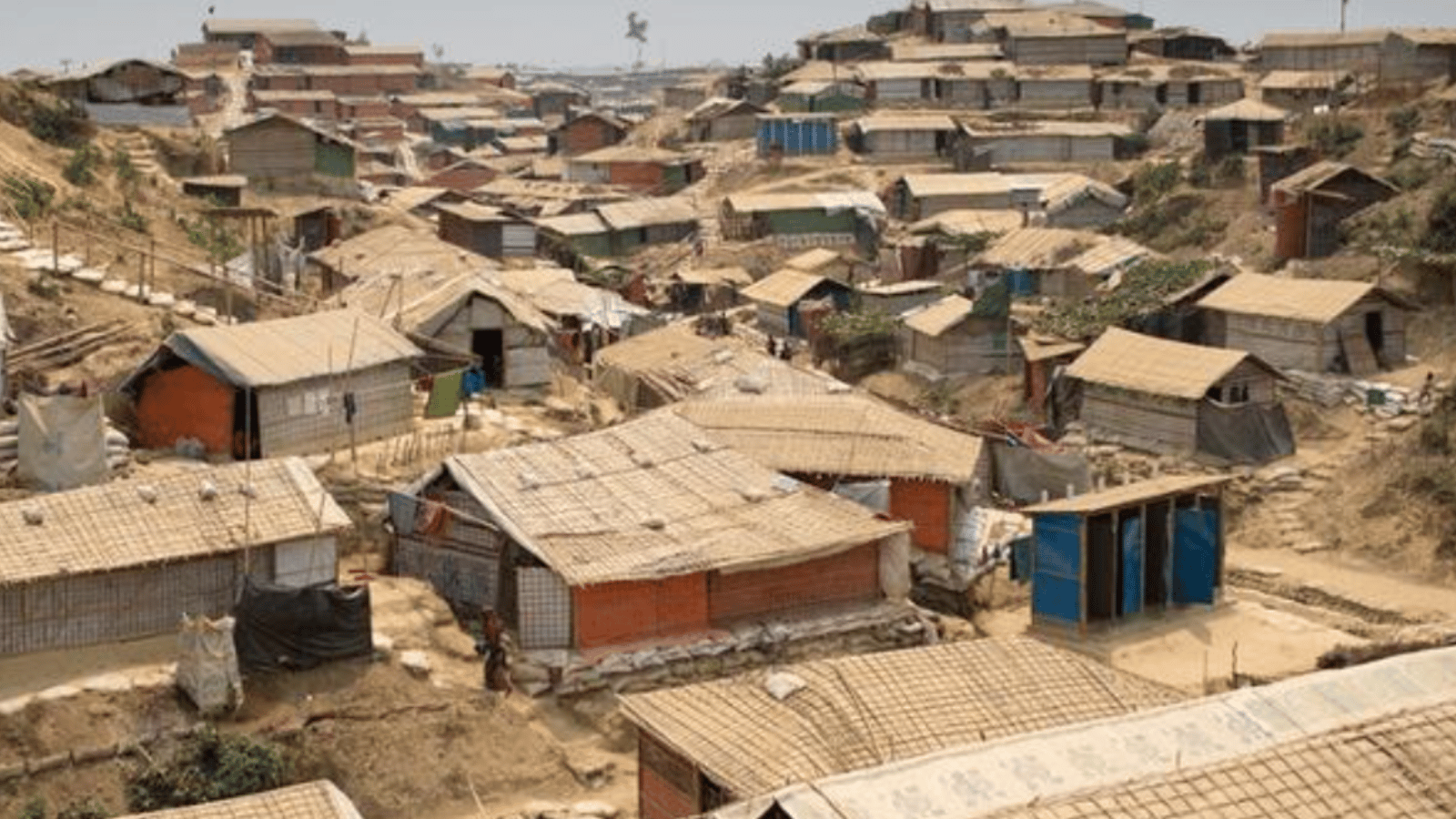

Other questions can be raised, such as if, when, and how migrant knowledge becomes local knowledge and local becomes indigenous, as well as what are their defining characteristics. These differences are important to consider. Whilst there is no consensus on the definitions of traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge, they are repeatedly used in research and indicate that there are different findings as per the labels which have been attributed to a community. For example, Ahmed’s (2021) research investigated the root causes of landslide vulnerability in Chittagong Hill Districts, Bangladesh. The findings indicate that the urbanised hillside communities (local) and the Rohingya refugees (migrant/refugee) residing in and around the Kutupalong camps had higher vulnerabilities to landslide risk than the tribal communities (indigenous). The difference in vulnerability was attributed to tribal communities’ “unique history, traditional knowledge, cultural heritage and lifestyle” (Ahmed, 2021, p. 1707). This can lead to the question of why there is a difference in the knowledge of the landscape. It is particularly interesting that the local and refugee communities were both found to be more vulnerable to landslide risk, given that when the research was conducted with the Rohingya refugees (in February 2020), they had arrived in Bangladesh only two and a half years prior – following the August 2017 Rohingya exodus. Therefore, it could be prematurely suggested that the migrant communities had similar knowledge as the locals and that this was developed only over a few years. However, further research would be needed to draw such a conclusion.

Kutupalong Refugee Camp, Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh. (Source: SH Saw Myint/Unsplash, 2022).

Traditional and indigenous knowledge is often spatially bound, i.e. tied to a specific area, and culturally bound, i.e. tied to a specific group or members of society. So if there is ‘transferability’ of knowledge, can displaced people use their knowledge and experience of similar hazards or disasters in their place of origin to understand their new physical surroundings?

Literature from disaster studies in urban and rural contexts, as well as climate change studies, evidence that perception and experience affect individual interpretation and action of risk information and behaviour on mitigating hazard risk (Bempah and Øyhus, 2017). It remains unknown whether these findings are similar for IDPs and refugees. For example, if the frequency of exposure to certain natural hazards increases knowledge and leads to improved disaster preparedness, response and recovery?

It is often thought that knowledge is gained either through teaching or experiences. So, is it the same in the context of environmental, natural hazards and disaster knowledge? The results are not uniform as to whether experiences with natural hazards or disasters influence the understanding of the hazard, a changed perception of the risk or coping strategies and appropriate responses. For example:

These four examples highlight how disaster knowledge and preparedness are heterogenous, changing between community and hazard type.

Whilst experience remains contested, there is strong evidence that disaster prevention strategies such as prior education, training and appropriate communication do reduce damage and loss from disasters (UNDRR, 2022). Hanson-Easey et al.’s (2018) study on risk communication strategies for immigrant and refugee communities in Australia found that hazard knowledge dissemination was most effective when it was in a participatory manner (two-way) and that the typical streams of risk communication (one-way, top-down) were inefficient for these communities. Moreover, Lejano, Rahman, and Kabir’s (2020) study of the empowerment of Rohingya refugees in Kutupalong camps against cyclone risks and impacts found that their participants, particularly the female participants, reported a higher valuation of self-agency after the risk communication workshops led by the researchers. There are many other examples, such as the annual International ShakeOut Earthquake Drill held predominantly in the USA and Japan, which have shown that regular education and training are one of the most effective strategies for loss and damage mitigation in the face of a disaster.

Further research is needed to focus on the nexus of displaced people, the environment, and natural hazards. As much as advancements have been made to include traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge into disaster-related frameworks, which is moving in a promising direction, there remains ambiguity in the terms used. More clarity is merited to understand how disaster and risk knowledge and practices can be transferred, acquired, and shared; especially in contexts where individuals may be unfamiliar with their physical surroundings. Lastly, using a risk and disaster lens to explore the relationship of IDPs and refugees with the environment, natural hazards, as well as their host community pushes the agenda further forwards of ensuring that no one gets left behind in disaster prevention, response, and recovery.

Acosta, L.A., Eugenio, E.A., Macandog, P.B.M., Magcale-Macandog, D.B., Lin, E.K.H., Abucay, E.R., Cura, A.L. and Primavera, M.G., (2016). Loss and damage from typhoon induced floods and landslides in the Philippines: community perceptions on climate impacts and adaptation options. International Journal of Global Warming, 9(1), pp.33-65. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGW.2016.074307

Ahmed, B., (2021). The root causes of landslide vulnerability in Bangladesh. Landslides, 18(5), pp.1707-1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01606-0

Bempah, S. A., and Øyhus, A. O. (2017). The role of social perception in disaster risk reduction: beliefs, perception, and attitudes regarding flood disasters in communities along the Volta River, Ghana. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 23, pp. 104-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.04.009

Collins, A.E., (2013). Applications of the disaster risk reduction approach to migration influenced by environmental change. Environmental science & policy, 27, pp.S112-S125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.005

Hanson-Easey, S., Every, D., Hansen, A. and Bi, P., (2018). Risk communication for new and emerging communities: the contingent role of social capital. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 28, pp.620-628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.01.012

Hyvärinen, J. and Vos, M., (2015). Developing a conceptual framework for investigating communication supporting community resilience. Societies, 5(3), pp.583-597. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5030583

Lejano, R.P., Rahman, M.S. and Kabir, L., (2020). Risk Communication for empowerment: Interventions in a Rohingya refugee settlement. Risk Analysis, 40(11), pp.2360-2372. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13541

Martin, A., (2005). Environmental conflict between refugee and host communities. Journal of peace research, 42(3), pp.329-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343305052015

Mishra, S., and Suar, D. (2007). Do lessons people learn determine disaster cognition and preparedness?. Psychology and Developing Societies, 19(2), pp. 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/097133360701900201

Oliver-Smith, A., (2018). Disasters and large-scale population dislocations: International and national responses. In Oxford research encyclopedia of natural hazard science.

Pollock, W., Wartman, J., Abou-Jaoude, G. and Grant, A., (2019). Risk at the margins: a natural hazards perspective on the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 36, p.101037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.11.026

Uekusa, S. and Matthewman, S., (2017). Vulnerable and resilient? Immigrants and refugees in the 2010–2011 Canterbury and Tohoku disasters. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 22, pp.355-361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.006

UNDRR, (2022). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030. [pdf] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. [Accessed 16 May 2022].

UNHCR (2020). ‘Forced displacement in 2020: Trends, crises and responses – UNHCR Flagship Reports’. [Accessed: 16 May 2022].

Van Den Hoek, J., Wrathall, D., and Friedrich, H., (2021) Population-Environment Research Network (PERN) Cyberseminars A Primer on Refugee-Environment Relationships.

Wisner, B., Gaillard, J.C. and Kelman, I., (2012). Framing disaster: Theories and stories seeking to understand hazards, vulnerability and risk. In The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction (pp. 18-33). Routledge.

Wulandari, Y., Sagala, S. and Coffey, M., (2016). The Impact of Major Geological Hazards to Resilience Community in Indonesia. Resilience Development Initiative.

Zaman, S., Sammonds, P., Ahmed, B. and Rahman, T., (2020). Disaster risk reduction in conflict contexts: Lessons learned from the lived experiences of Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 50, p.101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101694

This blog was originally published in October 2022 on the DENx blog (based at the Chr. Michelsen Institute) and is republished here with permission of the publishers.