With the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly known as COP27, underway in Eygpt, the NCHS is featuring a series of blogs from the Prioritizing the Displacement-Environment Nexus (DENx blog, based at the Chr. Michelsen Institute). This is the first blog of the series.

In 1990, Robert Bullard wrote Dumping in Dixie, a book in which he explored the systemic placement of garbage dumps in and around black working-class communities in the United States, and the resulting economic, psychological, and physical traumas on nearby residents. Connecting the link between racism, classism, and environmentalism, he identified a pattern of discriminatory urban planning that situated landfills and factories away from white, affluent communities, and in the backyards of black Americans. Later in the same year, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to explain how different social identities overlap, and how different forms of oppression intersect with and exacerbate each other. While originally used to understand the multiple forms of discrimination faced by black women in the United States, her intersectional approach has been adopted by researchers, advocates, and activists to understand overlapping power dynamics across a variety of different fields and pursuits for social justice. Both the work of Bullard and Crenshaw would go on to shape the notion of environmental justice, a form of analysis as much as it is a social movement, which states, among many assertions, that a society’s environmental burdens are disproportionately placed on its most vulnerable members.

In 2016, the University of British Columbia reported that more than 5.5 million people die prematurely every year due to household and outdoor air pollution. Prolonged exposure to particles released into the air from burning coal, wood, or gasoline from vehicle exhaust, buildings, manufacturing, and factories can contribute to the development of heart, skin, and lung diseases, just to name a few. The same is true for water pollution, in which potable water is contaminated by disease-causing bacteria and viruses as a result of agriculture, sewage, industrial fishing, oil spills, or radioactive substances. As water and air pollution degrade natural environments, the subsequent health impacts affect the entirety of a population. However, if we situate environmentally linked health impacts within a framework of environmental justice and intersectionality, we are able to understand how they affect marginalised communities more severely than the general population. This is especially true for refugee populations within host states.

In an era marked by protracted conflict and displacement, refugees are often placed in vulnerable and marginalised situations. While this precarity is certainly a result of the initial violence that caused displacement, it is also created and exacerbated by policies that restrict the rights of refugees, for example, by denying them legal residential status, the right to work, or access to health services. This is the case in Lebanon, where Syrian refugees[1] face these challenges. Often living in similar conditions as other marginalised populations in Lebanon – Palestinian or Iraqi refugees, migrant workers, and low-income Lebanese – they see difficulties in securing financial livelihoods, personal security, and struggle in the face of extreme poverty. This is multicausal; resulting from state inaction to address refugee informality, as well as larger macro events like the Lebanese economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, or the Beirut port explosion. It is these overlapping sources of precarity, along with ecologically harmful waste management practices, that prompt the conceptual use of intersectionality, and questions concerning environmental justice. This article, thus, unpacks the relationship between resulting air and water pollution, and the power dynamics that render Syrian refugees and other vulnerable segments of society in Lebanon at risk of these environmental hazards.

What does existing research say?

While there is extensive research on varying environmental challenges in Lebanon, this article is limited to discussing air and water pollution derived from poor waste management. Despite the wealth of literature, there is no official Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) or Ministry of Environment data at a national level about environmentally caused health problems (Massoud, Moukaddem, and Yassin 2017, 2). Researchers from the American University of Beirut (AUB) have attempted to fill this gap, and found that people living near garbage piles and open-burning sites are more likely to suffer from respiratory problems. These findings are extremely relevant to this line of questioning, but did not place a unique focus on refugees or other marginalised groups, nor include an intersectional framework. Fortunately, there is an overwhelming amount of research and methodology concerning intersectionality in refugee and forced migration studies that I have been able to rely on (Taha 2019, 29).

There is also research documenting the intersecting forms of marginalisation that Syrian refugees face in Lebanon. As Lebanon is neither party to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951, nor the 1967 Protocol (Saliba 2016, 213-216), the state is not obliged to give Syrians fleeing persecution the refugee status, and refrains from doing so in fear that granting such rights would encourage long-term settlement. In fact, over 80% of Syrian refugees lack legal residency, as the state stopped UNHCR from registering new Syrian refugees in 2015. This is apparent as well in the absence of policy governing Syrian refugees on a national level, with municipal and local initiatives being vague and often abandoned after inception (Stel 2021, 113). In the meantime, those not granted refugee status apply for residence permits, which is a notoriously difficult process that requires identity documents administered by the Syrian regime. Going back to Syria to retrieve these can often be fatal, and without any form of documentation, Syrian refugees are labeled as “illegal,” and face restrictions in movement in fear of arrest or deportation. They also encounter difficulty accessing education, health services, the judicial system, and government institutions, which are already failing due to compounding crises in Lebanon. Syrian refugees also do not have the right to work in the formal job market, which greatly limits financial capacity. Lastly, adequate housing is largely inaccessible, as Syrian refugees are not allowed to own property, and restricted financial capacity pushes them towards informally constructed housing with substandard living conditions (UN-Habitat 2018, 45).

Despite the research mentioned above, studies concerning environmental justice and refugees remain dismal. While there is no singular reason for this, such an absence does reflect a broader trend in forced migration literature, that conceptualises the relationship between refugees and the natural environment of the host state in terms of the resources consumed and pollution produced by the incoming population. This is certainly a relevant line of questioning considering that it is underdeveloped countries who host 84% of the world’s refugees, and that sudden influxes have led to deforestation or water pollution in the past. However, such research tends to focus solely on how the arrival of refugees inflames pre-existing environmental challenges, while failing to explore, in turn, how these same groups may be affected by pollution or environmental mismanagement in their newfound host state. Lebanon is no exception, demonstrated from UNDP Environmental Assessments of Lebanon in 2015. In this article, I would like to reverse this problem and show how Syrian refugees have both a marginal effect on the natural environment of their host state and are disproportionately affected by pollution through intersecting, institutionalised structures of marginalisation.

A brief history of Lebanese waste management

Following decades of unsustainable waste management policy, Lebanon has seen worsening environmental and public health conditions as a result. More recently, in 2015, when trash lined the streets of Beirut following the closure of the Naameh landfill, widespread protests for the sector to be reformed broke out. The state proposed the founding of the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill as a temporary solution, which substituted concrete reforms. Despite warnings in 2017 and 2019 from Human Rights Watch (HRW), there was a mass overflow of waste into surrounding areas, Beirut’s sewage system, and the Mediterranean Sea, when the facility stopped accepting trash in April 2020. This is particularly problematic considering the beleaguered sewer system, and for the coastal areas around the city normally used for swimming.

Due to the closure of Naameh landfill in Summer 2015, garbage quickly piled up and containers overflowed. (Source: Hassan Chamoun, 2015.)

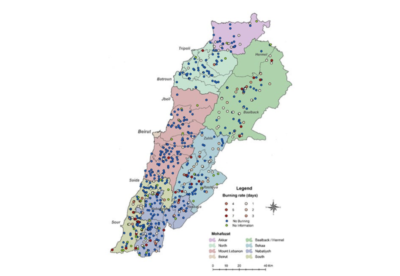

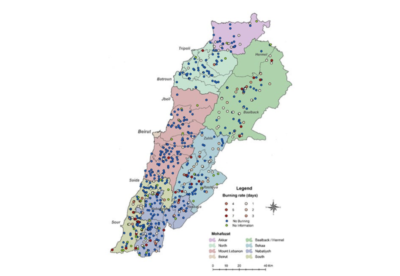

Since the Lebanese government has consistently failed to provide proper waste disposal mechanisms to its citizens, people have often resorted to burning their household waste in open spaces as an alternative. However, a range of scientific studies have shown that inhaling emissions produced from open burning sites pose a threat to health, and can lead to heart diseases, cancer, skin diseases, asthma, and respiratory illnesses. HRW, in an exhaustive article on open burning in Lebanon, found that people living near open burning sites were reporting these very health problems. With data provided by the Ministry of Environment and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), they were also able to see where these burnings were taking place, as shown below. While happening at many informal locations, open burning was also taking place at municipality dumps and waste sites.

More than 900 open dumping sites, including 641 Municipal garbage dumps, in Lebanon that experience varying frequencies of open burnings. (Source: Lebanese Ministry of Environment & UNDP, 2017).

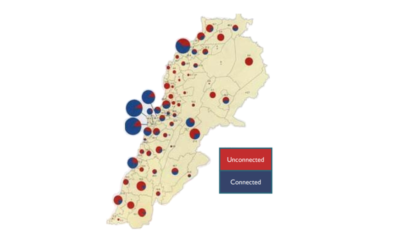

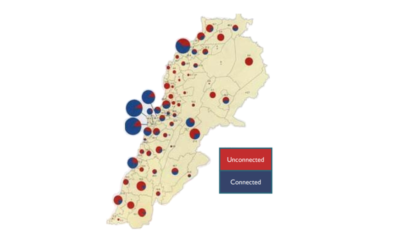

Unfortunately, it’s not just the burning sites. Lebanon’s sewage system is brimming with material waste, often as a result of overflowing landfills, along with factory and individual dumping. Lebanon’s sewer system is also highly exclusive; less than 60% of buildings in Lebanon have access to a sewer line, and instead rely on septic tanks and dumping waste into surrounding water sources like rivers, lakes, and wells (Geara-Matta 2010, 8). A map from the Atlas of Lebanon highlights the disparity.

Percentage of buildings in Lebanon that are connected or unconnected to a sewer line. (Source: Atlas of Lebanon, 2004)

How is this affecting Syrian refugees?

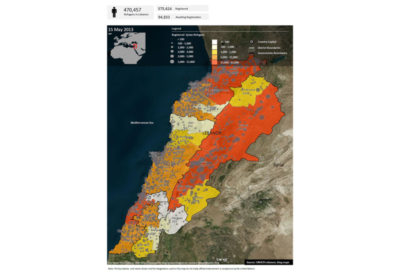

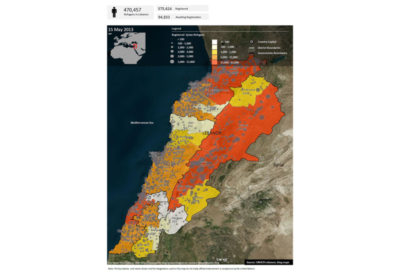

The lack of proper waste management has resulted in negative health impacts for Lebanese society at large, but the marginalisation that Syrian refugees in Lebanon face has made environmental challenges even more complex. To begin, the map below from UNHCR gives an understanding of where Syrian refugees are living.

The open burning map shows that sites used daily were concentrated in the Bekaa valley and the South, which both see high concentrations of Syrian refugees (see Map C). With no national relocation program, Syrian refugees decide where to live based on social relations, word of mouth, and their own financial capacity (UN-Habitat 2018, 45). While most refugees live in urban contexts – largely renting informally constructed housing that is overcrowded, poorly weatherproofed, with inadequate ventilation – many also live in informal tented settlements, which are rented on land in rural areas. In both cases, they are not able to protect themselves from particles released by burning garbage nearby, and many of them are also not connected to the municipal sewage system.

Syrian refugees by district in Lebanon. (Source: UNHCR’s Operations Data Portal, 2013).

In this dynamic, the marginalisation of Syrian refugees both creates, and perpetuates, exposure to air and water pollution. This begins with financial precarity imposed by lack of access to the formal job market, which results in decisions to take, cheaper, and more exposed living arrangements. Historic levels of inflation (over 140%) and mass unemployment (now at 40%) resulting from the economic crisis, make unsafe housing conditions even more unavoidable. The pollution of natural water sources means that neither tap water nor well water is safe to drink, and as a result, the majority of Syrian refugees’ potable water in residential areas comes from bottles (VASyR 2020, 53). While bottled water is a relatively small fee compared to most household goods, it is yet still another expense.

There are few avenues for recourse in such instances, as Syrian refugees with an “illegal” or stigmatised status are unable to stand up to landlords who randomly raise the cost of rent (UN-Habitat 2018, 44). If a health concern develops as a result of continued exposure, they also have difficulties accessing treatment, as the 2020 Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon (VASyR) explains, since cost is the predominant reason for Syrian refugees not seeking medical care. Life-saving medicines are similarly out of reach, as their prices have also skyrocketed following the removal of state subsidies. However, it is even more difficult for a refugee without a Lebanese residency permit or any form of documentation to seek medical care due to fears for their safety or deportation.

The environmental inequity experienced by refugees is even more stark when we look at the ratio of waste produced by Syrian refugees compared to the rest of Lebanese society. While Syrian refugees bear the brunt of the negative health effects from open-burning sites, it was found in 2015 in an Environmental Impact Assessment of the Syrian Conflict in Lebanon, that Syrian refugees produced roughly 15.7% of the total municipal solid waste in Lebanon that year, which is proportional to their current percentage of the population (EASC 2015, UNHCR 2021). Despite this, the compounding forms of marginalisation that Syrian refugees result in a disproportionate exposure to trash burnings of waste produced by Lebanese society en masse.

An activist climbs an electrical pole to take full view of the garbage secretly dumped in a forest just north of Beirut. (Source: Hassan Chamoun, 2015.)

The need for environmental coalition-building among marginalised groups

The current multidimensional poverty rate in Lebanon is 78% (ESCWA 2021, 29) and more and more people face intersecting forms of financial precarity. Among them, Syrian refugees, 90% of whom live in extreme poverty, are one of the most marginalised groups. Drawing on concepts of intersectionality and environmental justice, this article argues how the intersecting effects of marginalisation also extend to environmental risks, including air and water pollution from open burning of waste. While this environmental vulnerability is due to the particular challenges Syrian refugees face, including those related to their status and institutional treatment, it also reflects the widespread precariousness they share with other disadvantaged groups.

Refugees often share similar struggles to other marginalised populations in their newfound host states (Darling 2017, 179), and this is certainly true concerning environmental challenges in Lebanon, where Palestinian or Iraqi refugees, migrant workers, and low-income Lebanese are vulnerable for different reasons. Waste burning-induced pollution definitively affects all of these groups, yet for varying causes and with varying effects. For example, as many members of marginalised groups experience heterogenous forms of financial and social precarity, many rent homes with substandard living conditions – which are more exposed to air and water pollution –and later face a respectively diverse number of barriers to accessing healthcare, varying by nationality, economic status, gender, and race.

If environmental justice-based policy and practice rests, in part, upon equal protection from, and equal distribution of ecological burden, then we must attempt to understand which groups in society are most severely impacted, while acknowledging that everyone is at risk. The Lebanese government recently announced a plan to deport 15,000 refugees a month back to Syria, and have been inciting violence between local populations by blaming Syrian refugees for shortages of bread and fuel. This not only will place Syrians at the mercy of a regime who, over a decade ago, caused them to flee for their lives, but will continue to perpetuate tension between groups living in the same spaces, facing similar problems. Contrary to this, I assert that open waste burnings provide marginalised groups – normally at odds – the chance to build trust, solidarity, and coalition at the local level in response. While difficult to form in practice, Syrian refugees and other vulnerable populations stand to benefit, whether existing as a platform for collective solution-building, or to advocate against/for certain policies. Such collaboration would certainly lead to creative, bottom-up answers to multidimensional poverty, and by extension, environmental injustice.

[1] I use the term “refugee” as outlined in the 1967 Protocol of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, despite many Syrians in Lebanon not officially receiving the title.

References

Bullard, Robert D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 3rd ed. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

Darling, Jonathan. 2017. “Forced Migration and the City: Irregularity, Informality, and the Politics of Presence.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (2): 178–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516629004.

Geara-Matta, Darine, Régis Moilleron, Antoine El Samarani, Catherine Lorgeoux, and Ghassan Chebbo. 2010. “State of Art about Water Uses and Wastewater Management in Lebanon.” In World Wide Workshop for Young Environmental Scientists: 2010, edited by Daniel Thevenot. Vol. WWW-YES-2010. WWW-YES. Arcueil, France.

Taha, Dina. 2019. “Intersectionality and Other Critical Approaches in Refugee Research An Annotated Bibliography.” Local Engagement Refugee Research Network Paper 2019 (3).

Saliba, Issam. 2016. “Refugee Law and Policy: Lebanon.”

Massoud, May A., Tala Moukaddem, and Nasser Yassin. 2017. “INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES: The Path to Informed Policies: Environmental Health Indicators and the Challenges of Developing a Surveillance System in Lebanon.” Journal of Environmental Health 79 (8): E1–7. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26329743.

Lebanese Ministry of Environment, EU, and UNDP. 2015. Lebanon Environmental Assessment of the Syrian Conflict & Priority Interventions Updated Fact Sheet 2015.

UN-Habitat and UNHCR. 2018. Housing, Land and Property Issues of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon from Homs City: Implications of the Protracted Refugee Crisis.

UNHCR. 2014. “The Number of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon Passes the 1 Million Mark.” Accessed June 1, 2021.

UNHCR, WFP, and UNICEF. 2020. Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon.

Stel, Nora. 2020. Hybrid Political Order and the Politics of Uncertainty: Refugee Governance in Lebanon. Routledge Research in Ignorance Studies. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Hyperlinks

Associated Press. 2022. “Syrian Refugees Anxious Over Lebanon’s Plans to Deport Them.” 2022.

Awada, Nohad. 2022. “The Effects of the Economic Collapse in Lebanon.” The Borgen Project.

Brauer, Michael. 2016. “The Global Burden of Disease from Air Pollution.” In AAAS 2016 Annual Meeting: Global Science Engagement.

Galer, Sophia Smith. 2018. “Lebanon Is Drowning in Its Own Waste.” BBC.

Global Voices. 2015. “Lebanon’s ‘You Stink’ Protests.”

Human Rights Watch. 2017. “‘As If You’re Inhaling Your Death’: The Health Risks of Burning Waste in Lebanon.”

NRC. 2017. “Syrian Refugees Deprived of Basic Human Rights – Lebanon | ReliefWeb.”

Shah, Omer Karasapan and Sajjad. 2021. “Why Syrian Refugees in Lebanon Are a Crisis within a Crisis.” Brookings (blog).

This blog was originally published in August 2022 on the DENx blog (based at the Chr. Michelsen Institute) and is republished here with permission of the publishers.