This blog was originally published on BlISS, the blog of the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) and is re-posted here.

Back in 2015, cardboard placards bearing the words ‘Refugees Welcome’ that were shown in public spaces became an important way for ordinary European citizens to demonstrate solidarity with refugees and other migrants arriving en masse in Europe at the time. Citizen-led initiatives staffed by volunteers mushroomed, providing crucial assistance to refugees when humanitarian organisations were surprised and overwhelmed. But has something changed over the years as the amount of refugees entering Europe became smaller? What happened to these smaller grassroots initiatives as state and professional humanitarian actors gradually took over?

The arrival of migrants to Europe during the summer of 2015 and in the succeeding months saw massive political attention and media coverage at the time due to the sheer scale of the influx. Also remarkable was the widespread mobilisation of volunteers who helped refugees during and after their arduous journeys. Besides those initiatives led by civil society networks, many of the volunteers were ordinary citizens who had never or rarely been involved in volunteer initiatives before. They mobilised across Europe to provide basic assistance to refugees traversing Europe in a number of ways, for example in the form of food, shelter, clothes, access to Wi-Fi, and access to electrical outlets for charging mobile phones.

As the number of people wanting to help grew rapidly, it became necessary to organise volunteers and create structures. And so a flurry of new organisations arose in 2015 in Greece, the north of France around Calais, as well as in Paris – and basically in most of the European countries receiving an increased number of refugees between 2015 and 2016. Yet, as government policies on migration became increasingly strict and as fewer refugees arrived – at least to other European countries than Greece, where those who’ve made it there have mostly been stuck – what has become of these initiatives?

Following two of the main Norwegian volunteer initiatives created in 2015 can give us an insight into different paths some of these organisations have taken. Refugees Welcome Norway (RWN) and A Drop in the Ocean (Dråpen i Havet – DiH) are two initiatives who took quite different paths, with one assisting refugees arriving in Norway and the other one organising volunteers to go help in Greece. Refugees Welcome Norway became the umbrella organisation for most of the spontaneous volunteer efforts that popped up, first in Oslo, and then across several other cities in Norway. It took its name from other similar organisations that were being formed in Germany and most other European countries at the time.

The context in which the two initiatives emerged changed over the next year – albeit in different ways. In Norway, fewer refugees arrived from 2016 onwards, primarily due to reinforced border controls, the returning of asylum seekers to Russia (who had crossed over to Norway at its northern border with Russia), and increased restrictions on family reunification. While RWN for a couple of weeks in August and September 2015 was busy providing basic assistance to those waiting in front of the police registration office, itself unprepared for these new arrivals, a new reception and registration office established by the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration by mid-October meant that immediate assistance became the responsibility of the state in collaboration with the Norwegian Red Cross.

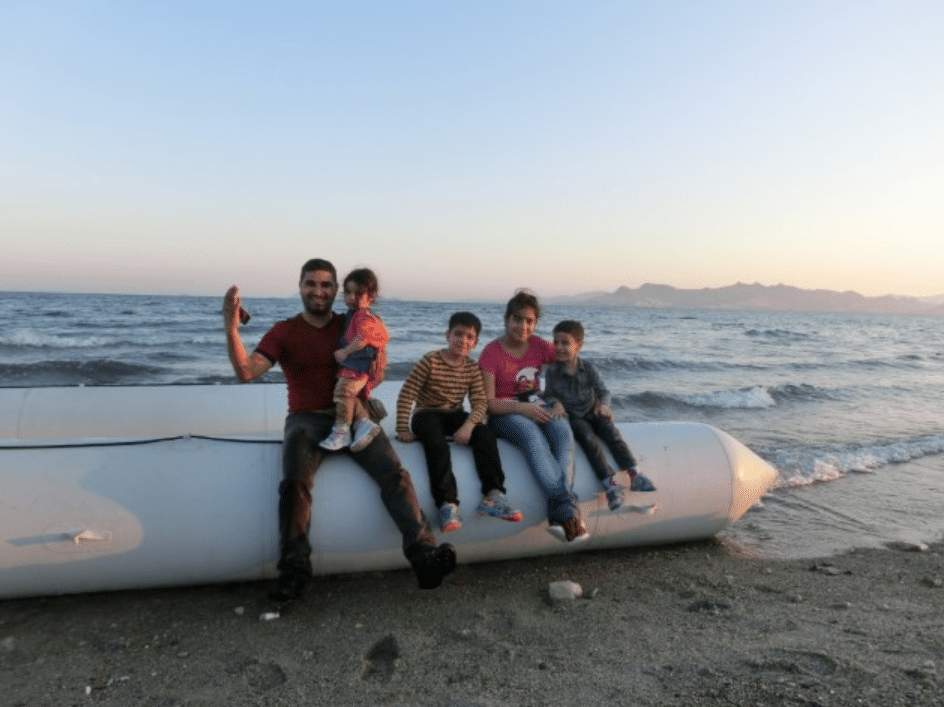

In Greece, the situation changed in a different way: fewer refugees and other migrants arrived from March 2016 onwards following the entering into force of the EU-Turkey agreement – yet some boats still arrived in varying numbers in the subsequent years. More importantly, Greece’s border to Europe was sealed off, and those having arrived on the islands were prevented from moving further. For the volunteers in place, the work shifted from reception on the beaches to working in the various ‘camps’ that had been established on the islands. While many more established humanitarian organisations by then had set up their own operations, DiH felt its support was still needed.

The two organisations developed in different ways over the years, both adapting to changing needs, as well as to varying levels of volunteer ‘supply’, yet both continuing to be characterised by volunteering, either as a political force for change or as individuals contributing to benevolent acts at different levels. As fewer migrants actually reached Norway, the then-leaders of RWN shifted their attention to political lobbying – notably against the government’s forced returns of migrants to Russia. Others involved in RWN in 2015 and 2016 in the meantime launched other local initiatives, which can be read as direct spin-offs from the activities of RWN in the early days: from neighbourhood integration projects (offering the possibility to act as contact points for newly arrived refugees in volunteers’ neighbourhoods) to a second-hand shop handing out clothes to those in need. Several key leaders of RWN also drew on the structure that had been established earlier, with local chapters emerging in multiple cities and common systems made ready to organise, recruit, and deploy volunteers should the number refugees and other migrants rise again.

DiH developed in a different way: it sought to develop itself into a professional humanitarian organisation, all the while not replicating the undesirable sides of the sector. The organisation in many ways sees itself as a reaction to these, i.e. to the formalised structures and bureaucracy plaguing professional humanitarian organisations. When I visited their facilities on the outskirts of Athens a few years ago, they would stress how DiH volunteers were directly interacting with the refugees, getting to know them, as opposed to officials of international organisations who were too busy with paperwork inside their bunker offices. DiH has also become more involved in political lobbying in recent years, in particular towards the Norwegian government and decision-makers, for example by organising awareness campaigns to draw attention to the dire conditions of refugees in the Moria camp and other similar places, or by pressuring Norway to accept more refugees from Greece.

What both organisations have had in common is a strong emphasis on their origins as “popular movements”, based on a multitude of spontaneous desires to “do something” to help out. While formalising their structures, professionalising and adapting to changing needs, they continue to stress that it “should be easy to help”. Both of them have also over these years developed new volunteer recruitment strategies designed precisely to continue to “make it easy”, and to attract new volunteers when these were no longer coming in in large numbers.

These benevolent acts can be understood both as emerging out of a desire or “need” to help fellow human beings in vulnerable situations (as such identifying primarily as humanitarian acts), as well as acts meant to protest against the non-action or insufficient response by the state and professional humanitarian organisations (as such self-defining as part of a broader social or political movement). Many initiatives started as the former, and evolved into the latter – with many of these volunteers arguing about the impossibility of remaining neutral and apolitical in the face of the injustices lived by the migrants. The intersection between humanitarian needs and protection needs, as well acts of helping out amidst state-led efforts to keep migrants away, makes this an interesting microcosm – also to study what is required for humanitarian aid to be precisely that – a humanitarianism based on humanity and impartiality. While most of the volunteer-based responses to the situation arising in 2015 have evolved into socially and politically engaged initiatives and have defined their actions as “humanitarian” to varying degrees, they nevertheless continue to challenge how humanitarian responses should be understood and practiced in highly politicised contexts.

This blog post is based on an article titled ‘Making It “Easy to Help”: The Evolution of Norwegian Volunteer Initiatives for Refugees’ that was published in International Migration. The article can be accessed freely here.