This post is part of a series of reflections on “Refuge”, by Alexander Betts and Paul Collier.

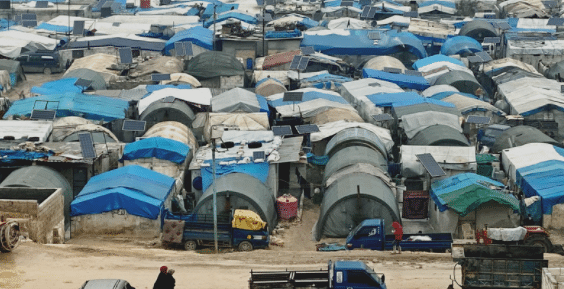

One of the most pressing challenges of our time is the fact that there are over 65 million persons around the world who are forced to migrate. Tragically, the international community’s response is marked by the maintenance of refugee and internally displaced person (IDP) camps in the South which hold refugees in limbo for decades.

Alexander Betts and Paul Collier rightly denounce the inhumanity of states which refuse to resettle refuges. They go on to propose safe havens in developing countries where private corporations and investors could provide work to refugees and citizens of host countries alike. Of concern, the authors pay insufficient attention to the need for strengthened legal perspectives to identify protection concerns raised by their model.

Betts and Collier suggest that refugees should be allowed to seek resettlement after five to ten years if no other solution (return or local integration) is possible. However, they do not address the fact that denying a person freedom of movement is a violation in itself, and their model would risk violating this, as well as a span of other human rights. With increased focus on private actors playing a greater role in the “safe havens”, there is also concern about the accountability of corporations, UNHCR/IOM, host states, and NGOs.[1] The authors do not address this fully, nor do they explain how to guarantee transparency when so many non-state actors are involved. On the contrary, they seem to indicate that international organizations (IOs), media, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) pressure should be sufficient to prevent exploitation. It may be suggested that since IOs themselves have been criticized for insufficient accountability in camps, there is no guarantee that they would be able to guarantee the accountability of other non-state actors. Certainly this is evident in the cases of private companies which run detention/reception centers in the West, with little oversight by UNHCR or civil society.

Betts and Collier state that UNHCR excels in humanitarian aid in camps and legal advice to governments, but state that these are no longer the primary skills needed to ensure refugee protection in the twenty-first century (p.58). It is undeniable that the maintenance of protracted camps are not adequate solutions, but there remains a strong need for UNHCR to give legal advice to governments in light of the epidemic of immigration reforms resulting in the adoption of accelerated and fast-track procedures to process asylum claims and diminishment of legal aid, right of appeal, and suspension of deportation.[2] While much of the media focuses on the construction of walls and increase of border patrols to keep out asylum seekers, the most effective measures for increasing deportations have been the construction of restrictive interpretations of the criteria for accessing territory to seek asylum and the conditions for receiving protection. The proper response to this trend requires the serious engagement of human rights lawyers.

The transformation of a broken refugee system requires a holistic approach, one that seeks to include legal perspectives, instead of excluding them.

References

[1] See Maja Janmyr, Protecting Civilians in Refugee Camps: Unable and Unwilling States, UNHCR and International Responsibility (Brill 2014).

[2] ECRE, Accelerated, prioritized and Fast-Track Asylum Procedures: Legal Frameworks and Practice in Europe (May 2017)

Cecilia M. Bailliet is Professor, Director of the Masters Program in Public International Law at the University of Oslo. Bailliet researches transnational and cross-disciplinary issues within international law including general public international law, human rights, refugee law, counter-terrorism, and peace.