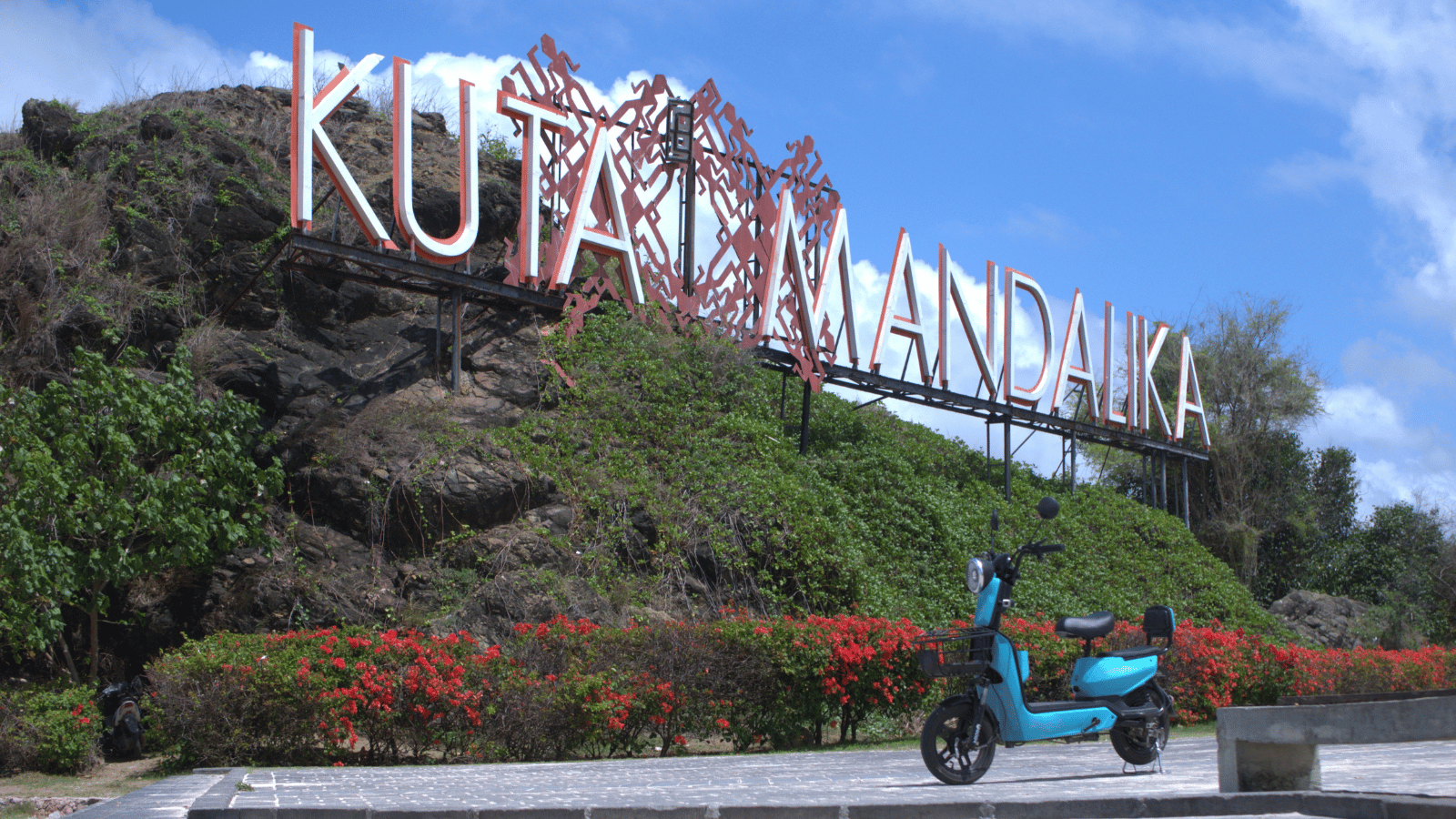

Displacement often occurs as these major multi-billion dollar projects require ‘green fields’ – sites cleared of local populations. This situation allows for the development of ‘untouched’ sites ready for tourists without local interactions. So, for instance, the enviable objective of sustainability can be bent into a commercial distortion when global capital enters into an equation dislodging local populations in favour of pristine environments. This exclusive space is important for the development and protection of commercial operators and their investors. At Mandalika, for instance, this ‘green fields’ site allowed for the building of a new hotel complex, with several hotels to be managed by multinational hospitality company ACCOR, and the development of a MotoGP motorcycle racecourse (and stadium) by Vinci Construction, a major global construction company operating in over 100 countries. All these activities have been funded by significant domestic and international finance, such as over $200m in funding from a Chinese Bank (the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and significant domestic funding. These mega projects, legitimated in the name of ‘development’, jobs and poverty-alleviation, are pragmatically having the effect of shifting power from local control to wealthy outsiders and globally mobile elites.

shifting power from local control to wealthy outsiders and globally mobile elites

The Bergen workshop considered these mega tourism projects and the global capital that facilitated these developments. We considered what these sites of consumption and leisure tell us about opportunities to develop new modes of regulatory solutions in order to confront larger global challenges. Essentially, how are such infrastructure projects changing politics, law and humanitarian issues across the globe?

Local governance, state jurisdictions and global conundrums

These mega tourism developments are radically altering local governance arrangements. These changes can be identified through a privatisation of policing and security arrangements and their exclusive nature, which has led to conflicts with local communities in many projects leading to forcible land acquisition and communities being relocated to make way for these developments. For instance, there have been allegations that the Mandalika project has led to forceful, or at least coercive, land acquisitions to clear land for the development. Exclusive tourism projects require ‘empty’ land. Whether these allegations are correct or not, the nature of these projects makes them susceptible to this outcome.

mega tourism developments are radically altering local governance arrangements

These projects are transnational in the strictest interpretation of the term. They can involve, for example, European construction businesses, American hotel management companies, and Chinese banks. They may be physically located in Indonesia or Morocco but the legal relationships, and risks, that control them are situated across an array of jurisdictions. The challenge for humanitarian organisations is how do they manage these diffuse legal relationships that facilitate projects that through their very nature displace people and potentially lead to human rights violations.

Human rights violations can occur when the state entities (such as the police and/or military) or private security groups confuse the protection of private property with brute force. Therefore, if genuine land acquisitions are moving slowly the financial incentives may lead to the exclusion of local populations in less than humane ways.

Regulating global capital

Neither forced displacements or human rights violations are inevitable outcomes. But if global capital can jump borders with ease and states (and private interests) can be induced by the glitter of gold then regulatory interventions are necessary to avoid the worst aspects of infrastructure projects.

The regulatory interventions used need to confront a slippery jurisdictional environment. In order to consider new answers to these tricky jurisdictional arrangements, the Bergen workshop brought together an array of scholarly disciplines to understand the nature of these projects and their implications. It is necessary at this point, to consider how the use of state institutions, such as courts, and privatised contractual relationships can allow for accountability. Projects that allow for commercial development should not dislodge local property rights, lead to human rights violations under the cloak of commercial-in-confidence arrangements and they should ensure the protection of community interests, such as access to communal land, religious and heritage sites.

Any forum dealing with complex problems needs to consider our disciplinary strengths and weaknesses. Lawyers often seek to simplify issues and make them appear neat and systematically solvable. Problems are simplified to be solved. While anthropologists seek to engage their subjects with nuance and intricacy. Essentially, complexity is the outcome. And then geographers seek to consider what and how place plays into social problems. But place and space do not necessarily equal a lawyer’s conception of the bordered, enclosed, notion of jurisdiction.

With this all said, we offer three recommendations ̶ two legal and one that engages with tourism expectations. These recommendations will consider how to transform the processes and expectations of these mega-tourism projects. In doing so, it is our expectation that global legal platforms will start to become part of the solution to global socio-political and environmental problems.

First, one of the important business elements of international commercial arbitration is that it is a confidential process and secret outcome. This allows companies to keep their activities, partnerships and problems private. Secrecy of arbitral proceedings allows for businesses to avoid unwanted scrutiny and ensure parties can resolve conflicts (and where necessary maintain commercial relationships after the dispute). These legal outcomes are legitimate expectations for business; however, it means that many major infrastructure arrangements or business activities lack public transparency. Consequently, disputes over multi-billion dollar projects can go without public or political debate across the developing (and developed) world. How can property law disputes or human rights violations be properly settled if large parts of commercial disputes are resolved secretly?

In order to answer this question, we would take two steps. These situations occur because arbitration privatises and removes commercial disputes largely from domestic courts. But states, and domestic courts, are not irrelevant. In order to enforce arbitral decisions, the New York Convention (1958), provides a system for domestic courts to enforce them. Therefore, the first step would be for domestic courts, or the New York Convention itself to be amended, to consider local property rights, local customary law or human rights when enforcing, or refusing to enforce, an arbitral award. And the second step of this procedural change when enforcing these arbitrations is that the decision itself should be made publicly accessible – transparency is, to borrow the cliché, the best disinfectant. This two-step procedural amendment will make these privatised legal processes significantly more visible and allow for the scrutiny of sensitive projects.

The second major recommendation would be to place terms into these transnational contracts that identify special requirements on the parties to the contract (and their agents). These contractual terms would be aimed at protecting local communities, property rights and enforcing human rights obligations. These contractual inclusions would change the underlying foundations of these major infrastructure projects and oblige parties to carefully consider how they undertook their activities.

Our third recommendation is not legal, but rather political. We would suggest that tourism strategies stop promoting untouched beaches and tropical island fantasies and embrace local communities in their design and marketing strategies. This would mean that local communities would become part of these major projects rather than impediments to their implementation. The management of local community relations and potential unfair property acquisition practices are real trigger points for human rights violations. Therefore, if the business motivation for human rights violations disappear, this is a better outcome than resolving the consequences of these humanitarian problems. That said, we believe that the enclavic tourism model that tends to perpetuate economic inequality ought to be scaled back in favour of more equitable forms of tourism development.

Conclusion

The Bergen workshop investigated global legal platforms and their consequences, considering case studies that emerged from across Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Gordian knots are not resolved quickly, however, through these case studies we considered the mechanics of the transnational commerce and the seed funding from the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies (NCHS) enabled discussions that allow for the reconceptualisation of these projects, and the development of recommendations, where fluid jurisdictions have complicated regulatory solutions. The seeds have now been sown for constructive regulatory remedies to be developed.