The complex politics of humanitarian technology

This blog explores the challenges associated with the use of biometrics for the delivery of humanitarian aid in Yemen, including privacy and data protection considerations.

30.06.2021

Maria-Louise Clausen (DIIS) & Bruno Oliveira Martins (PRIO)

The introduction of biometrics in Yemen is a prime example of challenges related to the use of biometric solutions in humanitarian contexts. The complexity of the situation in Yemen needs to be acknowledged by policy makers and other stakeholders involved in the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the country.

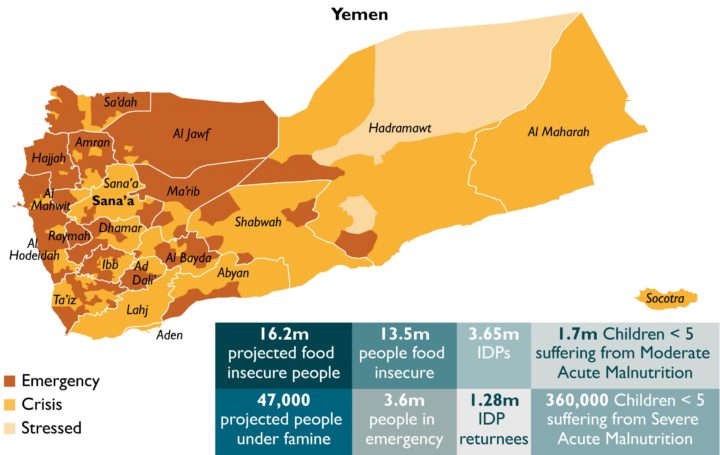

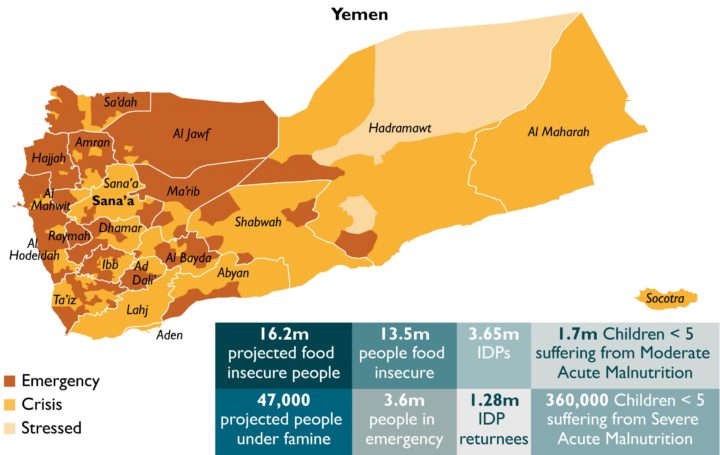

The humanitarian crisis in Yemen

Yemen is experiencing a humanitarian catastrophe. Currently, a majority of Yemeni, more than 24 million people – 80 percent of the population – are in need of humanitarian assistance to cover their basic needs. According to the UN, more than 16 million of those face crises levels of food insecurity and, of those, 3.5 million women and children require acute treatment for malnutrition. A child dies every 10 minutes from diseases, such as measles and diphtheria, that could easily be prevented, leading UN Secretary-General António Guterres to describe childhood in Yemen as a special kind of hell.

This humanitarian catastrophe is man-made.

The truism that reality is complex should not be used to detract from this simple but unpleasant fact. The catastrophe in Yemen has developed to its current unfathomable level because of choices that have allowed it to continue and deteriorate. Some of these have been deliberate whereas others have been accidental or the result of decisions with seemingly unintended side effects.

Cutting aid is a death sentence

The international community has struggled to find effective strategies for alleviating the suffering of ordinary Yemeni. Simultaneously, belligerents on the ground repeatedly demonstrate blatant disregard for the lives of the people they purport to defend and represent. The lack of trustworthy data and the absence of simple solutions can lead to resignation. The most recent UN donor conference had an aid goal of $3.85 billion but only $1.7 billion was pledged, meaning that as of April 2021 aid agencies are only reaching half of the 16 million people targeted for food assistance every month. Clearly, a lack of engagement with Yemen has direct implications for the thousands of men, women and children that suffer the consequences of this conflict every day.

Challenging context for humanitarian work

Humanitarian aid agencies point to Yemen as a complex and challenging context for humanitarian work. They face bureaucratic and political obstacles and restrictions on movement that limit access to beneficiaries, as well as difficulties in reaching parts of Yemen due to the dispersion of settlements, and weak infrastructure that has deteriorated further during the conflict. Further, the highly unstable security situation impedes effective humanitarian assistance delivery. Finally, there is a lack of reliable data, making it difficult for aid agencies to properly track and document both needs and effects of aid. This is only exacerbated by the conflicting parties lack of transparency and accountability. In Yemen, humanitarian aid is big business.

Biometric-based humanitarian responses

As explored in the policy brief Piloting Humanitarian Biometrics in Yemen: Aid Transparency versus Violation of Privacy?, the World Food Programme (WFP) has developed a digital assistance platform, SCOPE, to manage the registration of and provision of humanitarian assistance and entitlements for over 50 million beneficiaries worldwide. In Yemen, the WFP has applied a mobile Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping approach to conduct remote phone-based data collection and food-security monitoring and has implemented a Commodity Voucher system as a transfer mechanism for beneficiaries. In the government-controlled areas in the south of Yemen, the WFP has registered more than 1.6 million beneficiaries to date, but the Houthi authorities in the north of Yemen have been slow to accept the roll-out of biometric registration.

The WFP has argued that the introduction of a biometric registration system would help prevent diversion and ensure that food reaches those who need it most. Biometrics is envisioned to simplify registration and identification of beneficiaries as many Yemenis do not have identification documents. In any case, as explored further in the aforementioned policy brief, biometric data is more reliable than paper documents that can be stolen or manipulated. The WFP also accentuates that biometric registration has the potential to reduce fraud by increasing the traceability of assistance. If beneficiaries are biometrically registered, it supports a high degree of versatility and the ability to quickly adjust relevant services in a volatile environment where conflict might force families to relocate on short notice.

Humanitarian biometrics in Yemen: A complex case

The use of biometrics in Yemen is a prime example of the challenges related to the use of biometric solutions in humanitarian contexts. These challenges are inherently political and highlight the potential clash between values and objectives. The WFP maintains that biometric registration is necessary to prevent fraud and ensure effective aid distribution, whereas the Houthis accuse the WFP of violating Yemeni law by demanding control over biometric data. The Houthis allege that WFP is not neutral and a potential front for intelligence operations. The Houthis allegations were given credence by the recent controversy surrounding WFP’s partnership with the algorithm intelligence firm Palantir, and underscores the need for greater attention to responsible data management in the humanitarian sector. Distressed civilian Yemenis, in dire need for humanitarian assistance, are caught in the middle.

What is this ‘middle’?

The use of a biometric system, while having commendable intentions, creates new problems beyond the political disputes on the ground. The use of personal data of vulnerable people in a highly contested conflict further exposes local communities to risks. The problems raised by the expansive collection of personal data include theft, interception, or unintended/non-accountable exchange of private data where, in the contentious Yemeni context, such as a breach of privacy may potentially be a matter of life and death. Yet, the scale of the humanitarian crisis means that effective distribution of humanitarian aid is, quite literally, also a matter of life and death. In a situation where the humanitarian effort is underfunded, it is paramount to ensure effective, transparent, and accountable aid distribution.

The Yemeni case analysed in the policy brief points to the broader problems associated with reliance on new technology-based solutions to complex problems. The complexity of the situation illustrated in this case needs to be acknowledged by policy makers and other stakeholders involved in the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the country. While the potential for digital and new technology-based innovation to contribute to alleviating human suffering should be explored, the wider societal and political implications need to be considered by the ones involved in these processes.