Held at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), this breakfast seminar “Just Economic Sanctions?” explored the justification and human costs of economic sanctions.

Chair: Kristoffer Lidén (PRIO and NCHS Deputy Co-Director)

Welcome: Maria G. Jumbert (Research Director, PRIO and NCHS Co-Director)

Keynote: Economic Sanctions: A Moral Topology. Bashshar Haydar (American University of Beirut). Key-note on factors and features that play a role in grounding our judgments about the ethical justifiability of economic sanctions.

Perspectives:

Venezuela and the dark side of sanctions in a divided world. Benedicte Bull (Centre for Development and the Environment, University of Oslo)

Effects of international sanctions against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Arne Strand (Christian Michelsen Institute), online

Statistics on sanctions and the impact on women. Anna Marie Obermeier (PRIO)

Norway’s work on sanctions in the UN Security Council. Cathrine Andersen, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Concluding remarks: Lars Christie (Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences)

Please be aware this event will be held in-person and will not be live streamed.

Economic sanctions on trade and finance are used as a weapon short of war in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and supporting these sanctions is commonly perceived as a moral obligation. According to the Global Sanctions Data Base, economic sanctions often achieve their policy objectives, at least partially. In Syria, economic sanctions are a way of holding the Assad regime accountable for its atrocities but prevent reconstruction at the expense of the people. Meanwhile, heavy economic sanctions against the Taliban regime take a heavy humanitarian toll on the Afghan population. The United Against Inhumanity campaign for the release of Afghanistan’s frozen funds recently stated: ‘It is morally, politically, and economically wrong to make the people of Afghanistan pay – often with their lives – for a crisis not of their making.’ Similar critiques have been raised against the ongoing sanctions in Venezuela.

As current member of the UN Security Council, Norway is involved in decisions on a range of international sanctions regimes, and chairs the sanctions committees on North Korea (DPRK) and on Isil (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida, as well as being penholder on the Afghanistan file and the Syria humanitarian file. Norway also takes a stance on a range of sanctions without a UN Security Council mandate, like on Russia and Venezuela.

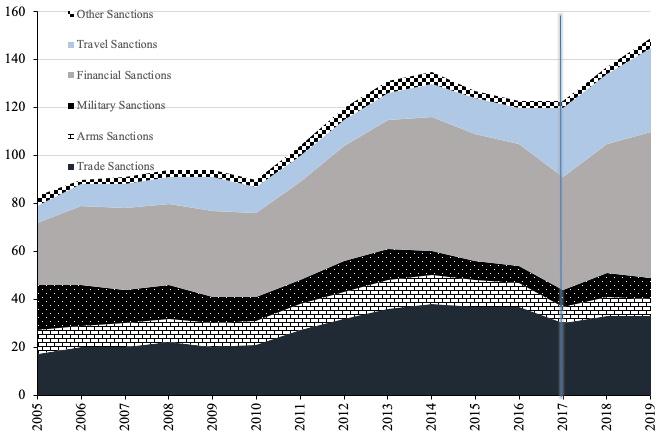

The use of international sanctions has increased steadily since 1950 (Figure 1, Global Sanctions Database), and sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council have increased dramatically since the end of the Cold War. In spite of this, little attention has been devoted to how sanctions regimes should be assessed ethically. As an alternative to war, economic sanctions are among the few coercive instruments at the disposal of states. When adopted multilaterally, they may serve to enforce international law. When states use them without a UN mandate, it is usually preferable to military means. Yet, economic sanctions are often criticised for being disproportionately harmful or for lacking in effects – or even being counterproductive – also when designated as ‘smart sanctions’.

There is evidently not a universal answer as to whether economic sanctions are morally right or wrong, as it depends on the circumstances. Still, when considering particular cases we inevitably operate with general theoretical assumptions that require critical examination.

The seminar was organised in association with the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies, with support from the Humeval scheme of the Research Council of Norway.