“Collateral damage” – that much maligned term for civilian victims of military operations – has been a recurring feature of the wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East for the past two decades. Cases where civilian casualties were clearly unintended have mostly involved US-forces or their allies, yet they very rarely end up in a court to decide culpability or award compensation. The recent outcome of a case that after more than ten years reached the European Court of Human Rights was therefore a watershed – a symbolic marker for thousands of similar civilian victims and their families.

The material facts of the case (Hanan vs Germany) are not in dispute. Late evening of 3 September 2009, the Taliban captured two fuel tankers that became stranded in a dried river-bed in Kunduz, a northern province of Afghanistan. The area was technically allocated to a German military contingent in a complex arrangement between the International Security Assistance Force and the Afghan government, whereby the forces of various NATO countries and other US allies had responsibility for providing “security assistance” in different parts of the country to keep the Taliban at bay. The commander of the nearest German base, Colonel Georg Klein, was told by a local informant that a large number of persons had gathered near the fuel tankers, and that they were all Taliban.

investigation showed that numerous civilians, including children, were killed

It was now close to midnight and all German personnel were on base. The colonel requested assistance for American planes to bomb the site. Two planes arrived and two 250-pound bombs were dropped. Subsequent investigation showed that numerous civilians, including children, were killed. They had come from a nearby village to collect free fuel from the stranded tankers. Casualty figures vary due to difficulties of ascertaining human remnants after the fireball caused by the exploding tankers. The UN mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) settled for 74 civilians deaths, including “many children”.

German authorities investigated and in April 2010 the Federal Prosecutor reported his findings. The colonel was cleared. He had not committed a war crime because he had not intended to kill civilians. He “reasonably believed” at the time that the persons assembling around the tankers were all Taliban. Thus he could not be prosecuted under international war crimes provisions incorporated into German law. Nor could he be prosecuted for wrongful deaths under domestic criminal law because the airstrikes were permitted under the laws governing armed conflict. Case closed.

Human rights activists took up the case of a local villager, Abdul Hanan, who had lost two young sons in the flames

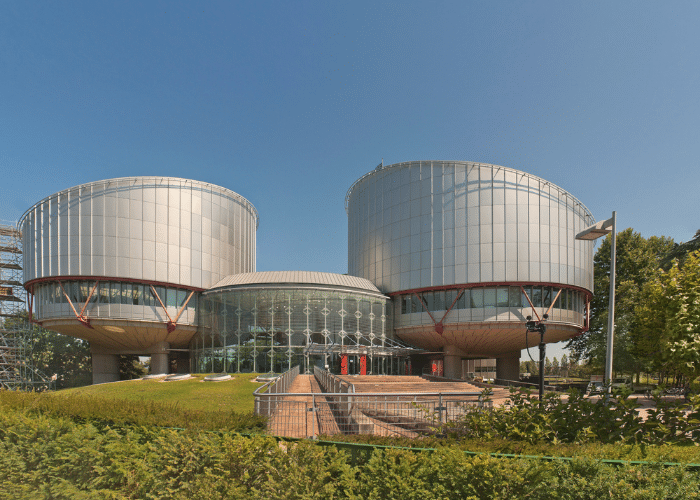

But the matter did not end there. Human rights activists took up the case of a local villager, Abdul Hanan, who had lost two young sons in the flames. They appealed to the European Court in Strasbourg, invoking the right to life of Art. 2 in the European Convention on Human rights. Choosing a minimalist strategy, Hanan’s supporters did not argue that Germany had violated the substance of Art 2 by taking the life of Hanan’s two sons, but merely that Germany had a duty to investigate the matter effectively, and had failed to do so.

The Court’s conclusions, issued last month, were based on long and (to a non-lawyer) intricate discussion of jurisdictional matters. Did the Court have jurisdiction over German actions undertaken extra-territorially in a UN-authorized multinational operation? Did German investigation in itself constitute recognition of responsibility that triggered the Court’s jurisdiction? In the end, the Court answered yes to the first question, and a qualified no to the second.

Some international lawyers saw the Court’s judgment as a partial victory for the applicability of European human rights law in extra-territorial situations. It might be a precedent that other civilian victims could draw comfort from. Others saw the Court as striking “a complex balance in the face of delicate issues” that might affect the willingness of states to participate in international military operations and investigate “deaths occurring in that context.”

The rest of the Court’s findings raises different questions. The Court found that the German investigation had been effective, and at no point did it question the German prosecutor’s conclusion: The colonel’s actions were justifiable. His subjective understanding of the situation at the time was what mattered, and he was convinced they were all Taliban.

Yet the Court did not ask:

The German prosecutors accepted the colonel’s assumption that no civilians would be out at night and that no civilians would be at the site of the strike since the nearest village was 850 meters away. No one asked if this was too far to walk for poor villagers when offered free fuel.

For a start, the colonel misinformed American forces when requesting air support, reporting that there were “troops in contact” on the ground. But, as the Court noted in an aside, “there had been no enemy contact in the literal sense of the term.” Neither German nor Afghan troops were on the site. Once the first plane arrived, the colonel refused the pilot’s suggestion to ‘buzz’ the site to scare people away rather than bomb them.

The colonel relied on one informant who lived nearby. The Court notes positively that the colonel made seven phone calls to that one informant. Calls to seven different sources might have yielded better intelligence. Moreover, the oil tankers were only 7 km away from the base. Could not the colonel have sent out a few men to assess the situation?

In other cases, the Court has applied the principles of international humanitarian law more robustly by asking such questions and awarded damages to the victims (Isayeva vs Russia). In this case, there was not much for Abdul Hanan to take home to his village of Omar Khel. For Colonel Klein, the matter ended better. He was in 2012 promoted to Brigadier General in the German army.