The surge in power prices, the fall in European currencies, and the fears of economic downturn in Europe as a result of collective European support for Ukraine threatens the ability to raise emergency relief funds for future humanitarian crises in the Global South.

As a direct consequence of the war in Ukraine, major OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members have been revising their aid budgets to address the immediate humanitarian crisis in its wake. A central component of these revisions has been the realignment of Official Development Assistance (ODA) earmarked for long-term development projects in the Global South, a move that may have far-reaching consequences for the recipient communities from whom aid has been diverted. If allowed to continue, these negative trends risk creating protracted humanitarian crises.

Even prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, narratives of development assistance had been undergoing a shift, with discussions concerning reductions in aid budgets based on the “effectiveness rationale” taking place in traditionally strong donor countries such as Sweden. In the United States, the head of the Agency for International Development (USAID) Samantha Power highlighted aid effectivity in a speech to the development contracting community entitled “Progress, not Programs” spurred by the “impact of aid” narrative.

In Norway, a donor that has committed to spending 1% of its GNI on development assistance, Finance Minister Trygve Slagsvold Vedum surprisingly announced on 12 May that 3.6bn NOK would be reallocated from international development projects to fund refugee-hosting costs at home. According to OECD criteria, refugee-hosting costs can be reported as development assistance for the first year. Following political outcry, reallocation was later revised to 1.5bn NOK, still a sizeable cut.

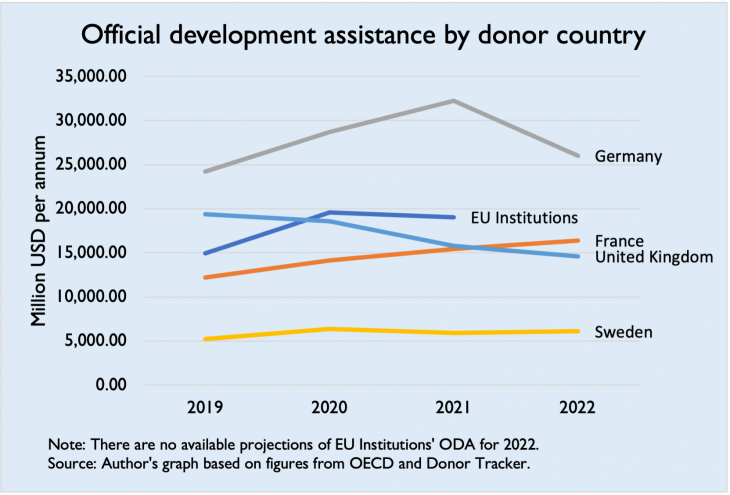

Other DAC states are following similar practices as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The realignment of development funding is particularly concerning in the context of a global economy slowly recovering from the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic which has disproportionately affected the Global South. Approximately 140 million more people were pushed into extreme poverty in 2021, a state which the World Bank estimates now affects 656 million people globally. Rising inflation, food and energy insecurity, climate-related emergencies, and supply-chain issues exacerbated by the war are further amplifying humanitarian crises with a greater impact on the world’s most disadvantaged communities. Resolving these issues will be a substantial challenge to policymakers in countries also facing domestic pressures relating to the dual crises of war and pandemic. Below is a graph illustrating changes in development assistance among OECD-DAC states (see figure).

There are no available projections of EU Institutions’ ODA for 2022. Source: Author’s graph based on figures from OECD (2022) and Donor Tracker (2022).

As evident from the data above, two major DAC members – Germany and the UK – have projected a decrease in ODA between 2021 and 2022. In the British case this corresponds with a 0.5% cap on development assistance implemented in late 2020 as a strategic measure to counteract the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy. This aid cut policy led to a £4.6bn decrease in the British aid budget in 2021 compared to the previous year. Beyond providing national governments with an impetus to withdraw funding from aid projects in order to address the ramifications of the pandemic at home, the distribution of ODA in 2020-21 was affected by reallocations of funding within aid budgets to provide support to international health programs providing immediate healthcare relief and managing the global rate of infection. EU donors alone effectively slashed $1.8 billion from development budgets in order to supply vaccine donations to ODA recipients.

The efficacy of development assistance is also challenged by the increasing tendency of donor states to favour loans over grants to meet ODA targets. The UN has emphasised that while development assistance must be scaled up in order to allow recipient states to meet the SDGs, grants should be prioritised over loan assistance. In the current context of rising inflation, loans are becoming increasingly harder to manage, adding to an existing debt crisis. As a result, ODA recipients already nearing debt distress may be forced to focus their finances on debt repayment rather than investing in development. While the OECD DAC has presented debt relief through ODA as one solution to this challenge, this approach would effectively entail cutting aid from other development projects in order to manage rising debt in recipient countries.

ODA recipients already nearing debt distress may be forced to focus their finances on debt repayment rather than investing in development

Though the size of ODA budgets does not appear to be affected by the war in Ukraine – at least following current projections – the allocation of funding within aid budgets has been affected. At the same time, humanitarian aid is facing response challenges to emergency appeals (besides those made for Ukraine). In addition, changes to national budgets such as increases in defence and military spending are likely to also affect the size of ODA grants. With no end in sight to the war in Ukraine and a looming reconstruction to follow, the compound effects of existing and new crises are likely to substantially impact the delivery of development assistance to the Global South.

While we are not able to provide reliable predictions of the long-term consequences of donor realignment in the context of the war in Ukraine, we can present some key assumptions based on the current situation.

Based on recent trends relating both to the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, it is not only evident that ODA delivery is threatened in terms of funding size, but that the allocation of funding within aid budgets and the types of funding reported as aid – including in-donor refugee-hosting costs, pandemic-related aid, loans over grants, and reporting debt cancellation as aid – undermine the quality of aid schemes. Projects in the Global South are particularly at risk of being underfunded or cancelled due to renewed priorities caused by the war that are also influenced by assessments of long-term development projects’ effectiveness. These priorities are not without consequences: by diverting long-term development funding away from unstable regions such as the Sahel, for example, the root causes behind the violence will remain unaddressed.

The war in Ukraine is also likely to have a detrimental effect on compliance with the SDGs. The existing gap in SDG funding was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, causing an additional $1trn annual decrease in donations (now an annual gap of $3.6trn), amounting to a funding gap of $17.9trn for the 2020-2025 period. The impact of refocusing attention away from meeting the SDGs in the backdrop of the war is twofold. First, by reallocating funding initially earmarked for national SDG targets, DAC members may fall short of delivering on their own commitments. Second, by reallocating money initially earmarked for ODA recipients, developing countries will not have the means to reach their SDG commitments.

At this critical moment in time, renewed commitment to meeting the SDGs is vital to avoid a climate disaster that will devastate the Global South and dramatically increase funding needs for both humanitarian aid and development assistance across the board.

Europe’s prospects for rapid economic recovery are not positive. Economic needs at home entail that governments are likely to continue focusing on support to domestic actors through business aid, as well as bolstering defence budgets. Added to this will be Ukraine reconstruction and recovery costs, including the cost of return migration for the approximately 5.5 million Ukrainian refugees recorded across Europe. A worst-case scenario could see social issues in DAC countries influencing mobilisation to populist movements whose politicians would make it more difficult to allocate funding to development aid abroad.

This post is written as part of a project on the consequences of the Ukraine conflict funded by NORAD and the MFA and led by Nic Marsh.

This blog was originally posted on the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) blog here and is republished here with the permission of the authors.